Bicycle camping is the most challenging and rewarding type of bicycle travel. With your complete home on your bike you are free to wander any where; such is the essence of bicycle touring. Self-containment and self-sufficiency are approachable ideals on a touring bicycle loaded with camping gear.

A touring bicycle camper has a complete shelter and a cooking and sleeping system and is able to carry two or more days of food and water. In dependent to a great degree, the cycle tourist travels anywhere the road leads without consuming nonrenewable fuel and without depending on a massive industrial complex to keep his or her ma chine running. Fuel for the body, and perhaps a little for the cookstove, is all that is required.

In addition to the aesthetics of such freedom, the economics are hard to beat. It’s possible to tour in most parts of the world for $5-$10 a day depending on your eating habits and the camping facilities you require or prefer. With another $20-$40 per month for incidentals such as laundry, sightseeing and personal needs, it’s feasible to tour for $170-$340 a month. How can you possibly afford to stay home?

What about the initial cost of your gear? Ease your mind with a few comparisons. The bicycle tourer comes out far ahead of a car camper or recreation al vehicle owner in initial outlay, but even when compared with backpacking, bicycling is not expensive. In addition to the high cost of a good pack, lightweight tent and hiking boots, back packing also means expensive light weight food for each trip plus transportation to and from the point of departure. Once the initial investment is made in bicycle touring equipment, however, there is little further outlay.

Your investment in camping equipment (depending on your plans) may exceed $200, but the gear is long-lived and touring itself costs little more than daily living expenses. You can do a lot to keep equipment expenditure down by using gear you already have or by renting the more expensive items like sleeping bags and tents. As you gain experience and expertise you can purchase what you need one piece at a time.

More important than acquisition of equipment is acquisition of the skills needed to become a competent cycle camper. Camping requires a degree of forethought and methodology in approach and practice. As you can’t expect to be a skilled tennis player your first time on the court, neither can you expect to be an expert camper on your first tour. Even if you have camped in your nonbicycling life, you will find things a little different under cycling circumstances. It’s possible to become a skilled camper in one particular environment in a relatively short time, but it can take years to develop the skills necessary to be at home in all circumstances and under all physical conditions. One of the great things about camping is that you can always learn more no matter what the level of your skills. You can learn a lot by reading books about camping, but most skills are developed by doing. Read; try to find an “old hand” to show you the basics; then go out and do it. You have nothing to lose but lack of experience.

Where to Camp

The choices in a given touring region might range from free public campgrounds to expensive private ones. Public campgrounds are operated by the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Most have a fee attached, but some are free (especially BLM sites). Services in public campgrounds usually include toilets, tables and fire pits; always check ahead in campground guides to make sure there is water if you need it. Most federal campgrounds are rustic and designed for tent camping, but many new ones are built primarily for recreational vehicles. Frequently these camps are located off paved highways on dirt roads; you might want to take this into consideration when planning your stops.

City and county campgrounds offer facilities similar to those of federal camps, but are located in more urban areas. These, too, generally have low fees. In midwestern America almost every small town has a city park in which you might be able to camp if you ask at nearby houses or at the local police station. Many town and city parks are gathering places for local youths on hot summer evenings; beer drinking and loud music can either delay your bedtime or add to your evening’s enjoyment, depending on your preferences.

Private campgrounds are scattered throughout the United States and Europe, especially along major highways. These vary from plush resorts with swimming pools, games, hot showers, laundries, stores and evening entertainment to more spartan types resembling public campgrounds. Many of these private camps are geared to the recreational vehicle and motorized camper; you may find yourself paying $4-$7 for the privilege of pitching your tent. Arguments do no good since you are paying for all of the extra facilities that are not affected by your mode of travel. Noise can be a problem in these camps as vehicles are packed closely together, but if you are in need of showers or laundry facilities, stores or company in the game room, private camps are there for your use.

One of the major advantages of bicycle camping is that you don’t really need a campground at all. In many areas, particularly on quieter roads, campgrounds are either nonexistent or so far apart as to be impractical for the cycling tourist’s daily use. In much of the United States and Canada where land is public (mostly in the West), you can camp just about anywhere. Water is the main problem but it can be carried with you if you plan ahead. On private land, permission to camp should be obtained with a courteous request to the landowner and a promise not to build a fire or leave trash behind. We have been invited to camp, use well water, and even share a meal with farmers and their families. Appearance and approach have a lot to do with the reception you get.

If you find yourself in a town or city overnight with no camping facilities (or no money for such), other places will sometimes do for quick stopovers. Schools, churchyards and even cemeteries serve if you are observant and careful in your selection. In other words, don’t expect to sleep late in a school yard on a weekday morning, don’t look for solitude on a Sunday morning camped out in a churchyard, and we personally avoid cemeteries on Halloween night. Any other time a cemetery guarantees you a peaceful sleep among quiet neighbors. Even in large cities, with a poncho or bivouac shelter, there are secluded spots among overgrown vegetation into which you can snuggle for a peaceful night. Unfortunately there is no way to determine sprinkler scheduling; you just have to take your chances on such things.

Selecting a Campsite

In an established campground, you have little control over or need for selecting your own campsite. On your own, however, there are several factors to think about. Water is of primary concern. Every gallon of water you carry weighs over eight pounds, so make your pedaling day as easy as possible. Dry camps are not impossible but a convenient water supply is preferable. If there is no piped or well water available, look for surface supplies — streams, lakes or springs. Assume any surface water is polluted unless proven other wise. A brook may look pristine yet have a dead horse or sheep herd ¼ mile up stream and out of your sight. Use Hala zone or Potable-Aqua tablets when you are not absolutely sure about the water. Diarrhea on a bicycle is a particular kind of hell.

When choosing a campsite don’t feel you have to be right next to the water supply, especially in public camp grounds. There is a continual parade to the water source, which destroys any privacy you may be seeking. Camping near a water surface assures you of a damp night. Try to get at least ten feet above the water for maximum dryness. Lakes and streams mean mosquito activity. By locating higher up in open areas you catch any breeze that hap pens along, which helps keep the bug situation under control.

You might want to settle on a sleeping spot to catch the early-morning sun or to avoid it, depending on your plans for the day. Choose a site that is as level as possible for sleeping — if you have to occupy a slope, place your head up-hill. Make sure your tent stakes are able to go into the ground before becoming too committed to a particular site. Underlying rock makes tent pitching frustrating if not impossible.

Most people head for the trees when searching out a campsite. Be sure that the trees you sleep under are healthy with no widow-makers (dead limbs) waiting for the next wind to loosen them. We once slept under a large yellow pine tree without a tent only to be jolted awake in the middle of the night when one of its huge cones dropped onto the foot of our sleeping bag. Had it landed on the other end we would have had serious headaches. Look around the area under a tree for debris — it didn’t get there by telekinesis. If there is a lot, avoid that area.

Before you start a campfire, make sure it’s legal and that the fire danger is low. Look for a source of dead, dry wood close by your campsite. Use nothing but dead wood, preferably that not lying directly on the ground where it has picked up moisture. Always use existing fire rings when possible; if you are the first to camp in an area, make sure no one after you will know you were there. Soak your fire dead out and disperse the rock ring, preferably back to the places the rocks came from.

In established campgrounds select a campsite away from outhouses and set back from major activity points. You have no choice over your neighbors, but people usually congregate as close to each other as possible when camping. If you value privacy, get as far into a lonesome-looking area as you can; usually others will avoid such places if they have a choice.

When camping outside of a camp ground, find a spot that cannot be seen from the road. Never advertise your presence. The only animal you really have to be wary of is man, yet in over 30 years of camping on three continents we have never had a confrontation or threatening experience with our fellow man or woman. Established camp grounds are possibly more dangerous because of the occasional drunk, traffic hazards and firearms dangers.

Don’t ignore the aesthetic considerations of a campsite. How you feel about a particular camp adds to your experience there. No amount of amenities makes up for a feeling of unease or discomfort. On the other hand, a beautiful scene can compensate for deficient camp facilities.

To Tent or Not to Tent

When bicycle touring, as with any overnight outdoor activity, we don’t recommend going without some means of providing shelter, whether you use it or not. Don’t make a shelter out of native materials; those days are long gone in this overpopulated world of limited re sources. Let living things live. Carry your own shelter with you.

Most people associate shelter with tents for some very good reasons. A tent provides shelter from the weather, whether that is dew, wind, rain or snow. It offers protection from insects and flying nuisances such as mosquitoes. It’s a place to store gear out of sight while cycling away from camp, and it offers privacy in today’s crowded camp grounds. Finally, it gives a degree of mental security as the night shadows fall. Tents make sense, but they are not mandatory due to their high cost and heavy weight for cycle touring.

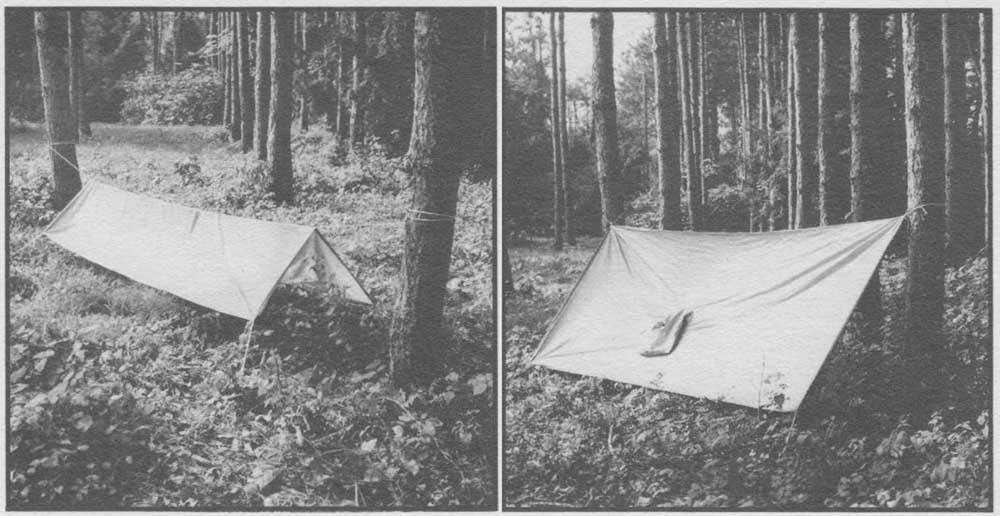

Tent substitutes are abundant and varied to meet your needs and your pocketbook. Our favorite is the simple backpacking poncho — a rectangular, 54 x 88-inch, 12-ounce piece of water proof nylon ($20). Wear it as a raincoat (too floppy for cycling), cover your gear and bicycle to keep weather off or pitch it one of many ways to provide yourself with an adequate shelter. Most models have grommets at the corners but we usually add extras around the edges for easier pitching and tying down. All you need is some nylon parachute cord, steel skewer stakes (5 ounces, 75 for 8), and some imagination to develop a variety of one-person shelters. As a professional backpacking guide and outfitter in Idaho, Tim used a poncho for his and his clients’ principal shelter all summer long in the high Rockies. Its weight, price and versatility are right for cycle camping.

If you want a larger shelter, a nylon tarp serves as well as the smaller poncho. Available in a variety of sizes, we like the 9 x 11-foot size best (2 lbs. 2 oz., $37).

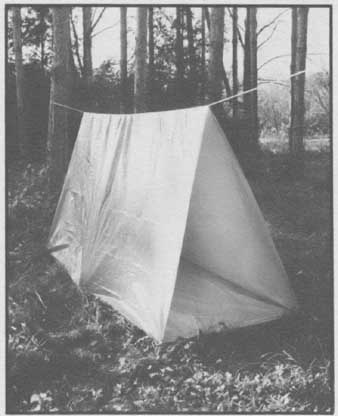

The tube tent is a favorite of many campers, although we don’t like it. De signed for one or two people, it’s made of three-mil polyethylene and is shaped like an open-ended tube (1 lb. 4 oz., $6; 2 lbs., $8). It’s fragile. A lot of people leave it when it becomes useless, so it’s an all-too-familiar sight half-buried in the dirt around campsites. If you use one, take it with you and dispose of it properly.

The poncho, tarp and tube tent offer adequate protection from weather, but not from mosquitoes. To solve this problem with the poncho, we designed and made a triangular piece of mosquito netting three feet high by four feet across, sewn in a cone shape with a tie string at the apex. Tied to the guideline running through the center of the poncho shelter, it hangs down over the head of the sleeping bag. We find it a cheap, lightweight, compact way to repel mosquitoes.

Poncho pitched as a lean-to (left) and a fly-shelter (right).

Pitched plastic tube tent.

Another tent substitute is the bivouac or bivy bag, a recent innovation in outdoor shelters. This is a close-fitting cover that encloses the sleeper and bag. The bottom is waterproof nylon and the top is Gore-Tex. Even though the sleeper is closely wrapped in the bivy bag, moisture does not collect in side due to the breathable top, yet it’s waterproof. Better models come with small mosquito-netted openings for ventilation in fair weather. Tim used a bivy bag made by Blue Puma (1 lb. 9 oz., $79) and reports it to be remarkably effective. Because of its compact size and light weight (just over 1 V lbs.), it’s an excellent cycle-camping shelter for one or two persons. Major drawbacks are cost ($50-si 00) and lack of internal storage space. It can be a bit tricky getting in and out of as well, especially in pouring rain.

Such tent substitutes make sense for the cycle camper. If you don’t want to invest the money in a tent, if you are concerned with keeping weight and bulk to a minimum, or if you limit your touring to dry environments, any of these will make your tour more comfort able and may even extend your touring season by several months.

When one of us tours alone, we don’t carry a tent. For two we prefer a small one, and when the whole family tours we always use a tent. We compensate for the weight by carrying one sleeping bag for each two persons.

If you decide in favor of tenting, consider these basic points. The primary function of a tent is to keep weather and bugs out, but it must also allow inner moisture to escape or you will be rained on from the inside each morning. Your body gives off a large amount of moisture both day and night. If your tent is totally waterproof, that moisture gathers on the roof and walls. Stay away from all tents that are completely waterproof; even with large window openings for ventilation you will have problems. Cotton tents can be waterproofed yet breathe, but they are too heavy for self-propelled travel.

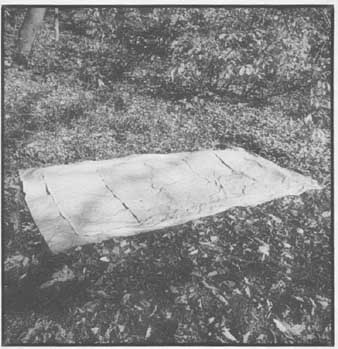

Bivy bag with ground cloth under it.

Most quality tents (with the exception of Cannondale which has a unique double-wall system) have waterproof nylon floors extending partially up the sides with breathable nylon on the top and upper sides. When used with an external fly (roof covering) of waterproof nylon, they won’t leak. Internal moisture passes through the roof and walls, yet the fly — pitched a few inches off the tent itself — keeps precipitation out. In anything except dry summer desert conditions, the fly is a necessity.

There are almost unlimited choices in tents. The continual search for the “salable new” has produced about every form imaginable. Many of these new designs are changes rather than improvements. Some are so complicated, requiring so many supporting poles, that it almost takes an M.I.T. graduate to erect them. Try doing it in a 40-mph wind just before a thunderstorm hits. Worse than that, what happens when you Jose or break a pole? With many of these models, one missing or broken pole means no tent. Our advice is to stick to tents that require simple, straight poles; the fewer the better. In an emergency you can always make or find a replacement in the woods or at the next hardware store. Many of the newer designs have a large number of seams and panels in the tent fabric. We see these only as more places for the tent to come apart or leak. Keep your gear simple.

When choosing a tent, first decide how much room you require. As space increases, so does weight. Most cyclists feel that the lighter the tent the better, but the first time you spend a couple of days waiting out a storm in a tent de signed for pups, your priorities change. Make sure the tent you choose has room for you and your gear. A two-per son tent usually suits one with a full complement of gear or two with the bulky gear out in the rain.

When touring with one or both of our children, we use a tent (7 x 7 feet) that has a 6’/ center pole. This Mckinley or Logan style has plenty of space for a family of three or four plus gear. Being able to stand up in it’s a nice feature, making the tent excellent for all types of outdoor activity. Two available models are the R.E.I. Mckinley 11(12 lbs. 4 oz., $361) and Sierra Designs’s 3-Man (8ibs., $250).

For two people, or one space-loving single, better designs are R.E.I.’s Ridge (6 lbs. 10 oz., $160) and Cirque (5 lbs. 12 oz., $120); Sierra Designs’s Star- flight (4 lbs. 9 oz., $145); Eureka’s Cats kill (6 lbs., $84) and Mojave (6 lbs., $77); L. L. Bean’s Allagash (6 lbs., $71); and Cannondale’s Susquehanna (7 lbs. 6 oz., $195). These are samples of the good tents presently available. You generally get what you pay for but don’t buy more than you need.

Tents come with their own stakes, but you might want to replace them with seven-to-ten-inch steel or aluminum skewer stakes for lighter weight. They can be easily pushed into most ground types with your hand or foot.

A tent is expensive, but look on it as an investment in a home away from home. The more you do to prolong the life of yours, the happier you will be in the long run. We always use a ground cloth under our tent to ward off dampness and to extend the life of the tent floor. A piece of two-to-four-mil plastic cut the same size as the tent bottom does the job. Mark one side “this side up” and always put it that way under your tent. As the ground cloth wears and becomes unusable, simply replace it with another from your local paint or hardware store; it’s better to replace it periodically than your tent’s floor.

While at the paint store buy a small (four-to-six-inch) wallpaper paste brush, then cut off the handle. This makes a great brush for keeping the inside of your tent clean; it’s smaller and cheaper than a whisk broom. It lasts longer, is lighter, and helps prolong the life of your tent as well as your sanity by keeping sand and pine needles out of your sleeping bag.

- Sleeping Bags and Covers -

You don’t need an expedition-type sleeping bag for bicycle touring unless you plan to ride your bike up Mount McKinley. The tendency is to overbuy. Quality sleeping bags can be had for as little as $35 or as much as $450. With some thought and planning you can end up with just the bag that suits your particular needs without a massive expenditure.

Perhaps no sleeping bag is best for you. You can save cash, weight and bulk by using a small, high-quality quilt or comforter in its place. Since you will be using some sort of pad under you, why bother with a two-layer sleeping system when one top layer will do as well? You get little insulating value from the bottom of a sleeping bag because it’s compressed under your body. Keep this option in mind, especially if you are traveling in pairs and want to save the weight and bulk of an extra bag.

If you sleep in pairs and opt for this method as we do, all you need is a good sleeping bag with a full-length zipper or a high-quality quilt or comforter. We have been using this system for years to good advantage. On our family bike tours the children use a Dacron comforter in the same manner; thus we carry only two “sleeping bags” for four people. Even when we lived in the Yukon Territory of northern Canada in a tent for four months, we didn’t take to separate bags until the temperature fell below 0°F at night. Families save a lot with this system. A single twin-size Dacron comforter (67 x 80 inches, 3 lbs. 9 oz., $34) is comfortable for two people down to 40° F. and can be used at home on a bed; twice the use for a reasonable price.

If you need to purchase a sleeping bag, you must decide on the type and the amount of fill in addition to the shape you want. There are three major types of fill: natural waterfowl down (duck or goose), man-made Dacron and Fortrel. Down is the traditional fill with advantages of lighter weight, compact- ability and breathability, the factor that gives it a large temperature-comfort range. Disadvantages are high cost, difficulty in cleaning and loss of warmth when wet.

Dacron Hollofil II and Fortrel Polar Guard are man-made fibers that are less expensive than down and easier to clean and they maintain a large percentage of their insulating ability when wet. However, they are heavier, less compactable and don’t breathe as readily as down. Therefore, they are more restricted in temperature-range performance.

Your choice depends on whether you will be bicycling in cold, damp climates where man-made fibers are a definite safety advantage, or whether you need the greater temperature range of down. Cost might be a factor as well (down is much more expensive). Excel lent bags are available with any of these types of fill.

The amount of fill you need is directly related to the minimum temperatures you expect on your tours. Amount of fill equals loft (the height of the bag when fully fluffed on a flat surface as measured from the surface itself to the top of the bag). Loft is the amount of dead-air space that provides insulation to keep you warm. It’s only effective when not compressed, so the fill on the bottom of the bag is relatively useless. Practically, then, loft is the total measurement of the bag divided in half.

Loft determines the warmth of the bag. The U.S. Army maintains that the “average” person needs 1.5 inches of loft to be comfortable sleeping at 40° F., 2 inches at 20° F. and 2.5 inches at 0°F. These figures don’t take into consideration such factors as windchill, type of shelter, and individual metabolism, which vary widely. Use them as a guide only. Generally, for a three-season bag (comfort to 20° F.) look for 2-2 1/2 pounds of down, or 2 1/4-3 pounds of man-made fiber. The temperature range of a bag depends on the elements of loft and breathability coupled with quality construction and shape.

Of the three basic shapes of sleeping bags — semi-rectangular (some times called semi-mummy), rectangular and mummy — the mummy is most efficient. At 40°F you lose up to half of your body heat through your head alone. At 5°F this figure increases to three-quarters. The mummy bag with its built-in head cover allows a sleeper to draw up the bag so only the nose and mouth are exposed. Its narrow shape is more efficient because of less surface area for heat transference. Mummy bags take a little getting used to at first but most people stop fighting them after two or three nights. It helps to think of a mummy bag as a thick skin that tosses and turns with you rather than a shell inside of which you attempt to turn.

Semi-rectangular bags are larger than the mummy style; some even have a head covering. Above 45°F you rarely need a head cover, and if you anticipate temperatures no lower than freezing (32°F.) a knit hat serves as well. Advantages of a semi-rectangular bag are added comfort due to extra leg room and the bag can be opened for use as a comforter if it has a full-length zipper. The third kind — full-size rectangular bags — are comfortable and capable of making excellent comforters, but we don’t recommend them for cycle touring due to excessive weight and bulk in areas not necessary for body comfort.

If you have a firm idea as to what you want in a sleeping cover and you deal with a reputable dealer or mail-order house, you won’t go far wrong. Be ware of the gung ho salesman who wants to outfit you for an expedition to the Himalayas. Buy the best quality you can, but don’t end up with a bag that is too hot for 90 percent of the places where you will be using it. For much of the United States, in the warmer half of the year, a bag good to 40°F is sufficient if you are using a tent. On those few nights that approach freezing, a wool-knit hat and a layer of dry clothing worn to bed will give adequate protection if not comfort.

A good sleeping bag should last a lifetime if taken care of. Use a heavy- duty nylon stuff bag to carry it. Line this with a plastic bag, then stuff — don’t roll — your bag into it. No stuff bag is water proof after it has been punctured with thousands of needle holes. You can trust seam sealant and hope the top do sure is away from the blast of the rain, or you can use an inner plastic bag and be assured of having a dry sleeping bag at the end of the day.

When not touring, air your bag completely and store it loosely in a dry place in a large pillowcase. If you leave it tightly compacted in the stuff bag, it will slowly lose its ability to spring back to maximum loft.

On tour, especially on cold nights, remove your bag from the stuff bag and fluff it up an hour or two before bedtime. This allows the fill to reach its maximum loft before you crawl in. If the dawn is bright and dry, open the bag to air in the sun for awhile to get rid of trapped body moisture that accumulates during the night.

To obtain maximum life expectancy from your bag, add a liner that can be removed for laundering. Don lined all of our bags using cotton/polyester flannel sheeting tied in with bias-tape ties. Since the liner can be untied and removed for cleaning, the bag itself rarely needs laundering — possibly the hardest wear a sleeping bag can get. The sheet adds a little weight and bulk, but fits into a regular-size nylon stuff bag and adds a bit of warmth on cold nights. It’s especially nice to slide bare into warm flannel instead of icy nylon.

Sleeping Pods

The pad under you is more important than the cover over you when it comes to insulation and warmth. A sleeping pad performs two functions; first, it cushions you from the hard ground. You really appreciate this after a long hard day on a bicycle seat, unless you are one of those fortunate few who can sleep soundly on a bed of rocks. Second, the pad acts as insulation between you and the cold ground. The bottom loft in your sleeping bag compresses to a useless amount under the weight of your body, so the thickness of the sleeping pad is critical in keeping your body heat from being transferred into the ground.

Sleeping pads come in three-quarter lengths (about 42-56 in.) and full lengths (72 in.). Widths vary from 20 to 24 inches. The full-length pad is more comfortable, of course, but heavier and more bulky. The three-quarter length is just as comfortable under the main part of the body; extra clothing or jackets can be used under the lower legs for insulation and comfort.

For overall comfort, an air mattress is hard to beat, but it provides little if any insulating value due to moving air in it. The air mattress is great for summer conditions, but is uncomfortable below 45 or 50°F. Besides providing comfort, the air mattress compacts nicely, a decided advantage for bike touring. The best air mattress we have found is Air Lift (small — 1 lb. 5 oz., $20.50; large — 2 lbs. 7 oz., $29.50) consisting of separate, replaceable tubes in a nylon cover.

Ensolite (small — 1 lb. 6 oz., $7.50; large — 1 lb. 13 oz., $12.75) and Blue- Foam (small — 6 oz., $4.75) represent the closed-cell type of sleeping pad so popular today. Each cell is enclosed so that small dead-air spaces trap and hold the air. It won’t absorb water so no protective covering is needed. These pads are very light, fairly compact, rugged and excellent insulators, but they leave a lot to be desired in comfort. The most common and useful thickness ( in.) just barely fools your bones into thinking they are not on the cold, hard ground.

More comfortable is the open-cell pad constructed of urethane foam. This type does not insulate as well as the closed-cell type, and will absorb water. It’s bulkier with a common thickness of 1 ½ inches. Most come with protective covers such as those sold by R.E.I. (small — 1 lb. 14 oz., $14; large — 2 lbs. 12 oz., $18.50).

A new pad on the market offers the tourist the best of both worlds. En closed in a nylon cover, it’s a sandwich of 1 ¼-inch open-cell foam with ¼-inch closed-cell foam. Even with its nylon cover, it should be carried on your bike in a waterproof plastic or nylon sack. This is an excellent product for the person who wants both insulation and comfort. The EMS Super Pad comes in small (1 lb. 10 oz., $15) and large (2 lbs. 14 oz., $19.50) sizes.

Which sleeping pad you prefer depends on your attitudes toward bulk, weight, comfort, durability and size. Whichever you choose, do use one. The bad old days of sleeping on the bare ground are gone forever. A modest expenditure for a good sleeping system will save you the money you might have spent for motels rather than facing another miserable night on the cold ground.

A ground cloth is an integral part of your sleeping system. If you are tenting, you are already aware of its advantages in preserving the tent floor and keeping moisture out. Even if you are using a poncho or tarp shelter (especially if you are using these) the ground cloth is a necessary item. It keeps moisture and dirt off your sleeping pad and cover, adding years of life to each. For maxi mum efficiency it should be a foot larger in length and width than your pad. The lightest and most durable ground cloth is made of coated nylon taffeta available for $3.50 a yard in a 55-inch width. A less expensive alternative is two-to four-mil polyethylene, which can easily be replaced as it wears out.

Mark your ground cloth on one side to insure that all the tree sap and gunk is on the bottom every time you use it. A nylon ground cloth doubles as a table cloth or picnic ground cover for maxi mum usage.

The most complete, high-quality sleeping system can be enhanced by a few maneuvers as you set up camp and prepare for your night’s sleep. Try to find as level a sleep site as possible and remove any small stones, sticks, pop-up tabs and bottle caps. Spread your ground cloth, then lie on it for a minute to check for anything missed or an undetected slant. If a slope is unavoidable, put your head uphill, it’s better to take care of these site-selection problems while still light when you are functioning with daytime perception. Struggling around at midnight to dislodge a rock under your shoulder is no fun.

If the night appears to be cold or your bag is thin from a long period of compression, open it and fluff well at least an hour before bedtime. Sleeping bare is probably the most comfortable, unconfining and relaxing way to sleep, but if you insist on clothing, make sure it’s absolutely dry. Don’t sleep in any clothing you cycled in that day as body moisture trapped in your clothes means a colder night. Depending on your tolerance and the minimum temperature you expect, add a knit hat and dry socks for maximum comfort.

A jacket or spare clothing inside your clothing bag serves as a pillow; add more clothing under your legs if the sleeping pad is short. For middle-of-the- night sanity, always put your light, watch and water bottle in the same easily accessible place.

Bumps in the Night

For those new to camping, the first few nights may be a bit unnerving. Most of us live very sheltered existences, with little experience in the normal nocturnal sounds of the wild. There is a whole world of little animals out there who do all their business in the night. They won’t harm you but tend to stumble around a bit. We have had mice unwittingly race across us, and Don once had a raccoon walk lazily over her in her sleeping bag. Skunks and raccoons are common night neighbors. The only thing you have to fear is your own panic. Lie still and you might be entertained; probably you will be left with a humorous story to tell around the next campfire.

Other nighttime .sounds are falling limbs, pinecones, and rocks and the wind whispering through treetops. Owls are famous for peopling the night with spooky sounds; learn to recognize them for what they are and your imagination has that much less to feed on. Aside from bears — and they’re mostly in national parks where they have lost their fear of man — there is nothing that will do you any real harm. Make sure your food is suspended out of harm’s way between two trees (not over your head) and you should pass the night well.

Sleeping out of doors is one of the most pleasant experiences imaginable, especially when you have taken the necessary steps to insure a comfortable bed. The first several nights you may be a little stiff and sore from cycling all day and sleeping in an unfamiliar bed. All of that passes with time and experience.

Food Preparation

Bicycle camping does not necessarily mean preparing your own meals.

If you don’t enjoy doing it or don’t want to carry the extra equipment, there is only money between you and taking all your meals in restaurants. Of course you must then cycle in places where there are restaurants that offer the type of food that both agrees with you and favors your cycling activity.

Food preparation is a normal, even enjoyable procedure for most cycle campers. In most areas of North America and Europe you are never more than two days from a supply point (grocery store) so it’s not necessary to carry large amounts of food. The food you buy need not be dehydrated or of special preparation, so you save money while enjoying fresh, familiar food. Frequently you can purchase your dinner and breakfast supplies toward the end of your cycling day so you don’t have to carry them any great distance.

Never be totally dependent on a store being open. We always carry one compact, dehydrated emergency meal in case we don’t make it to the next town or the store is closed when we get there. We have come close, but have never yet used it.

Preparing your own food does not always mean cooking. During the hot summer months when most cycle touring takes place, it’s easy to completely forgo cooking. When touring in summer we rarely cook since we crave cold foods and drinks. Read more about what to eat in Section thirteen.

Going without a stove, pots and fuel can save up to three or more pounds and a lot of bulk besides. This is tempting given the general availability of food on most tours. There are, however, two situations where you should cook; when temperatures are low so that you want and need warm food, and in Third World nations where food and water might be questionable. Even in the summer, hot food is a priority item in high- altitude touring.

If you decide not to cook, your only needs are eating utensils, tools for cut ting and opening, and a means of carrying fresh food. Cooking requires a decision to either carry a small pressure stove or opt for open fires.

Open-Fire Cooking

The traditional method of camp cooking is over an open campfire. Many people don’t feel as though they are camping unless they breathe in a little wood smoke. Aside from a romantic aspect, an open fire saves having to carry a stove, and you can use more than one pot at a time. On the other hand, open- fire cooking requires a degree of skill not common in our overly processed society. It takes more time to gather wood, build the fire, wait for a bed of coals, prepare the meal, clean the pots and extinguish the fire. You can get pretty grubby from that romantic aroma. The biggest drawback is that open fires are restricted or prohibited in many areas, with good reason. Fire permits are frequently required, and they are rare landowners who permit you to build a fire on their property. Overpopulation and environmental considerations work against your getting wood in the first place, unless you buy it in organized campgrounds. No matter how aesthetically pleasing the fireside, denuded trees, campfire-started wild- fires and old fire pits that mar the landscape all work to end the age of the open fire.

We’re not anti-campfire, having spent many memorable evenings with wood fires either in the open or in portable wood stoves. But for the camping cyclist primarily restricted to heavily traveled paved roads, the campfire is not usually a practical means of food preparation. If you do use a fire, make sure it’s both legal and safe for the area you are in. Try to use already established fire rings or pits rather than building a new one. Clear at least a ten-foot circle around your fire down to mineral earth (no humus, dry leaves, sticks and grass). Gather only dead, downed wood that has not picked up moisture from the ground. Keep your fire small using pieces of fuel that will completely burn up. Carry and use a small, stainless steel backpacking grate (3.5 oz., 5 x 15 inches, $5) to make your cooking easier and more efficient. Carry your pots in bags to keep from blackening the rest of your equipment. If you prefer to clean the outside of your pots each time, coat them with soap before using on the fire; the black comes off much more easily. Most important, make sure your fire is completely out by drowning it with water until you can stir the ashes with your bare hand. Fire can burn deep into some richly organic soils only to erupt days later into a wildfire.

Stoves

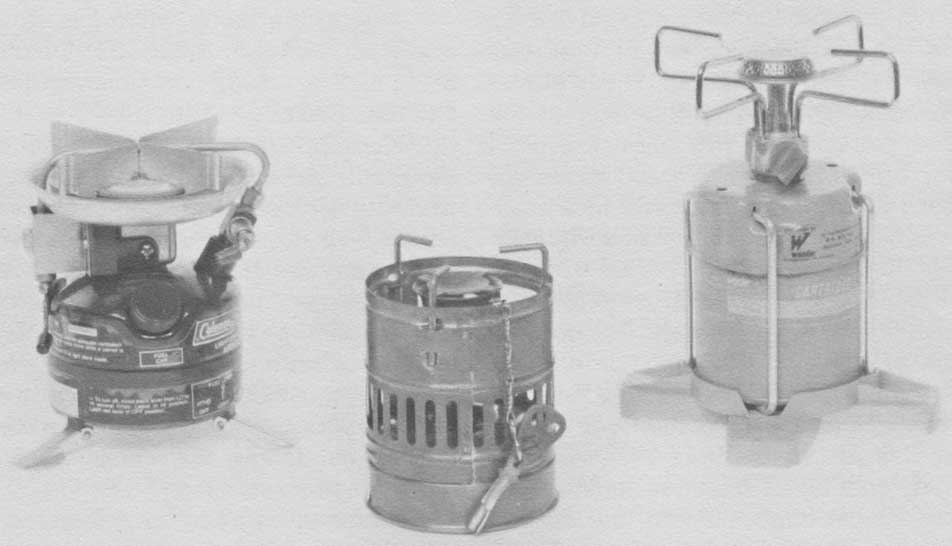

The so-called “backpacker” stove is an alternative to the open fire. It’s small, fast, efficient, clean and relatively easy to use. It poses no danger to the environment and leaves nothing be hind. On the minus side for the cycle tourist are its bulk and weight (1-2 lbs.), and the fact that on longer trips you must also carry extra fuel. These stoves are noisy, with no comparison to the quiet romance of the open fire. And they are not cheap. A good stove will cost you anywhere from $25 to $50, al though the investment is small considering its long life span.

Before you attempt to choose a stove to tour with, you must decide what type of fuel you prefer. Your choices are white gas, kerosene and butane. White gas (Blazo, Coleman fuel, Camplite, Campstove fuel) was once available in any quantity at most gas stations. It’s now almost impossible to find so you must purchase brand-name fuels in one-gallon cans at outrageous prices. That size is impractical for cycle touring, so you must carry small containers from home or use unleaded gasoline from service stations. Unleaded gas works, but over an extended period will plug your stove.

In spite of cost and quantity difficulties, white gas is highly efficient, generally available throughout the United States and Canada, and clean. It readily evaporates if spilled and no special starter fuel is needed to prime the stove, although many require priming with white gas, which can be a tricky procedure. Highly flammable, it needs to be used with caution. White gas can be impossible to find in many other countries; in Europe ask for naphtha and hope for the best.

Among the better white-gas stoves are Svea 123R (1 lb. 2 oz., $29), Optimus 8R (1 lb. 7 oz., $33), and Coleman Peak 1 (2 lbs., $28.50).

Kerosene (paraffin in the United Kingdom, petroleo in Latin America) is available all over the world. The kerosene stove is practical for the bicycle tourer with expansive plans. If you can’t get kerosene for some reason, you can use diesel fuel, stove oil or home heating oil. Kerosene is a relatively safe fuel in that it must be heated before it will ignite; if you spill some you have a mess but no real danger. Extremely efficient, it’s cheap to use.

Problems with kerosene relate to its difficulty to light. It requires special priming fuels; alcohol is the most common and is available at drugstores in most countries. Tubes of jellied alcohol are available, which are more convenient for the cyclist to carry. In a pinch, you can use gasoline to prime. Kerosene is smelly, dirty and won’t evaporate when you spill it. Two of the best kerosene stoves are the Optimus 45 (2 lbs. 7 oz., $40) and Optimus 00(1 lb. 11 oz., $37).

The third common stove fuel is butane. It’s available in many forms but for cycle touring, the disposable cartridge type is most practical. Butane is fast, simple to use since it requires no priming or preheating, and delightfully quiet.

Disadvantages are lack of efficiency compared with white gas or kerosene and dependence on expensive, difficult-to-find cartridges. In the United States and Canada replacements can be purchased at outdoor or sporting goods stores, while in Europe they are available at many campgrounds and tourist-type stores. As for the rest of the world, good luck. Another difficulty, especially for the cycle tourist, is that the cartridge must remain attached to the stove until emptied, a bulky requirement. When empty, the cartridges stink unless you tape over the hole; so they need to be disposed of properly and quickly. Good butane stoves include the GAZ Bleuet S-200 (1 lb. 13 oz., $12) and the GAZ Globetrotter (1 lb., $19.50). Cartridges for the S-200 weigh 11 ounces each and cost about $1.35; for the Globetrotter the cost is $1.19 and cartridges weigh 6 ounces each.

ABOVE: Three popular stoves: Coleman Peak, Svea 123 and GAZ Bleuet S-200.

The fuel type you choose depends on the extent of bicycle touring you anticipate as well as your own preferences in handling ease. Both white gas and kerosene stoves require attention to de tail and some experience in use — best gained in noncritical situations such as camping in your own backyard. If you want simplicity and don’t mind the shortcomings, pick a butane-burning stove. We use a Svea 123 (white gas) stove for tours of no more than a week or two in the United States and Canada. For longer than that, or outside those two countries, we use the Optimus 00 kerosene model due to its efficiency and more easily obtainable fuel.

Good operating techniques ease your job no matter which stove you use. Place the stove on a level, stable spot (not in the tent) where it’s sheltered from the wind as much as possible. Have your food ready to go before you light the stove; always use a lid for quicker, more efficient heating. When using white gas or kerosene, strain all questionable fuel through a rag or Cole man filter funnel (1 oz., $1 .50) as you fill the stove to prevent problems halfway through the stew.

Prime white-gas stoves using a three-inch section of plastic straw (with your finger over one end to provide suction) or an eyedropper to lift the fuel from the tank into the primer cup. Al ways tighten the tank filler cap before lighting, and never refill a hot stove. In very cold conditions insulate white-gas and butane stoves from cold ground or snow.

Extra fuel for a butane stove means carrying as many cartridges as you need or touring where they are readily available. With white gas or kerosene, extra fuel should be carried in a strong, leakproof metal container. This can be carried in one of your water-bottle cages if it fits properly; many cyclists carry one attached to the underside of the down tube, so it can’t harm other gear if the container leaks. You can carry kerosene in a good-quality water bottle. Be sure it’s well marked so there is no possibility of confusion with bottles containing water or drinkable liquids. Sigg makes an excellent, strong, round spun-aluminum fuel bottle with a good gasket and tight lid that is virtually leak- proof. Of the three sizes — 1/2 pint (2 oz., $4), 1 pint (4 oz., $4.50), and 1 quart (5.5 oz., $5) — the pint best fits into a water-bottle cage. Fuel can be carried in your panniers, but put the container in a plastic bag first in case the impossible leak occurs.

An excellent accessory for the Sigg fuel bottle is a pouring cap (1 oz., $1.50) to use when you fill your stove. It’s easy to control the flow so you will be able to dispense with a funnel if your fuel is clean.

ABOVE: Sigg Tourist Cook Kit (and Sigg fuel bottle) assembled with a Svea

123 stove and ready for use.

Cookware

How much do you plan to cook and for how large a group? Some people can get by with a number-two tomato can and a spoon (Tim), while others seem to need a full field kitchen (Don). Read through Section thirteen, “Food for Touring,” before making your final decisions on cookware and utensils. It might change, or at least define, your ideas on this subject.

A basic kit for two to four people is a set of two nesting aluminum pots with lids. Your stove should fit into the smaller pot for maximum compactness. Handles that can be removed or folded into the unit are best. Pots without handles can be lifted with a pliers device called a pot gripper (2 oz., $1.25).

The outfit we use most and like best for one to five people is the Sigg Tourist Cook Kit (1 lb. 8 oz., $25). This unit has two pans (3½ pt. and 2½ pt.), a lid that serves better as a pot than a skillet, a stove base (for the Svea 123), a wind protector and a pot gripper. The whole thing nests into a unit only 43% x 8¼ inches. The Optimus 00 kerosene stove fits into the basic cooking pots when the wind screen and Svea stove base are removed. (They are not needed for the Optimus 00.) You can purchase separately 6’/ aluminum Sigg plates (2 oz., $1.50), which nest into the Tourist Kit. If you like frying foods, carry along a Teflon-coated aluminum frying pan with holding handle (12 oz., $5.50).

When cycling with a group of six or more, you need two Tourist Cookers or a pot large enough to hold the whole unit. Your choice in cooking sets is endless, including the possibility of buying pots separately to fit your individual needs. For cycle camping use nesting units that incorporate your stove for maximum compactibility.

On long tours with large groups, especially when touring in isolated areas where prepared food is hard to get, the Optimus Mini-Oven (15 oz., $15) comes into its own. This sits on top of most small stoves and lets you cook up goodies such as bread, biscuits, pies and even cakes. Carrying along the basic ingredients is far easier than the completed product.

Another great cooking aid (mostly for large groups due to its size and weight) is the English-made Skyline four-quart pressure cooker (2 lbs. 13 oz., $34.50). It’s invaluable for quick cooking, especially at high altitudes. It enables you to include many grains and cereals in your cycling diet, which normally require too much time and fuel to be practical for camping. Saving fuel helps make up for added weight.

Your choice in cups and plates is almost limitless. Ever popular are stacking plastic mugs and the ubiquitous stainless steel Sierra cup (3 oz., $2). Stainless steel, unlike aluminum, won’t burn your lips when filled with hot fluid. We frequently use cups instead of plates, since food comes off the stove in single courses and cups are much easier to handle than hot aluminum plates. When touring with the children Don prefers deep, stacking plastic mugs, as food — especially liquids — is less likely to slosh around than with the shallow Sierra cups.

Any utensils will do although many prefer the light, stainless steel variety that clip together (3 oz., $1.50). Don’t forget a sharp, simple camp knife. You don’t need a ten-inch “macho” survival weapon. While Tim was guiding in Ida ho, he discovered that the biggest greenhorns always seemed to have the biggest knives. All you need is a sheath or folding knife with a four- or five-inch blade. Most wooden-handled boning knives available in hardware stores are fine. L.L. Bean sells an inexpensive, high-quality camp knife with sheath (Bean’s trout knife, 4 oz., $5). We used a folding knife for a while but got tired of cleaning cantaloupe seeds and fish scales out of the handle groove. Except for small tasks, multiple-blade knives are useless around the kitchen.

On longer trips you will have to have some means of keeping your knife sharp. More expensive, high-carbon steel knives require expensive stones or steels for sharpening, but cheap knives are sharpened easily (and frequently) with a small whetstone or sharpening steel. We like Herter’s convenient five- inch sharpening steel for all-around camp use ($2.75).

Don’t forget a can opener. Probably the greatest material contribution to civilization made by the armed forces has been the tiny GI or P-38 can opener (0.2 oz., 25c Tie a piece of red cord to it as it’s forever turning up lost.

A handy, specialized kitchen item necessary in desert areas is a folding water bottle. The best one we have found is Swedish-made, soft plastic with built-in wooden handles at each end. It holds 2’/2 gallons, has a spigot and can be rolled up into a compact bundle. We carry one .on many of our tours; it re fuses to wear out. Tim has rigged up a portable shower by attaching a water sprinkler to a piece of flexible plastic tubing, which fits tightly onto the spigot. When we arrive in camp early, we fill the bag, hang it in the sun to take the chill off the water and soon enjoy a makeshift shower.

Unfortunately, we know of no pre sent source for these Swedish bags, but check around. Other varieties of folding plastic bottles are readily available (2’/2 gal., 4 oz., $1.50). If you don’t carry an extra water container, yet get caught needing one partway through your tour, use a bleach bottle from the trash at a laundry. It cleans up easily, is reliable and free.

One last item to store with your kitchen gear is a supply of garbage bags. Save plastic bread sacks or pro duce bags for this purpose, or you can always use paper grocery bags as you buy food along the way. Carry your trash with you until you find a proper receptacle.

Packing Up

There it sits. All that stuff you are planning to take along on your tour. How are you ever going to get it all onto your bicycle? If you have planned care fully and are taking only what you know you will need, rather than what you think you will need, you should be OK. If the pile still looks impossible, go through it all separating those items you will be using every day or must have in certain situations. That extra-large cooking pot the pajamas, the full-size bath towel — essential or just nice to have? If necessary, make two piles; those things you absolutely can’t do without and those things you think are important to have along. If it all ends up in the first pile and it’s still too much, you have a problem. Better take along a spartan buddy on a big bike. Check your equipment against the lists for various types of tours in sect. A. These are not the final word, but what you have should resemble the suggested list.

For weekend motel touring, you can probably get all of your necessary items into a stuff bag that you can tie onto the top of the rear rack. A 10 x 20- inch stuff bag (3 oz., $5.50) is the least- expensive way to carry gear on short trips, or if you have a handlebar bag and seat bag you can put your gear into them.

For cycle camping, packing is a bit more complex. Organize your equipment into functional groups — kitchen, sleeping, shelter, clothing, recording (camera, note pads) and miscellaneous. Give some thought as to how and when you will be using various items and separate them accordingly.

To keep things both dry and organized, we use individual bags Don sews up from coated nylon taffeta material (55 in. wide, 2.7 oz., $3.50 yd.). Light, strong and waterproof, the material comes in a variety of colors, which permits easier identification either by different categories or by different members of the family or group. Digging through panniers at dusk when everything is in identical blue bags can be upsetting. You could number or label bags if you prefer one color.

We have clothing and toiletries bags for each family member, and separate bags for tools, shower shoes (usually wet and muddy), washcloths (also wet), gorp, writing materials, toys and food staples. We go bananas over bags.

Once everything is categorized and packed in whatever individual manner you prefer, decide what you want in your handlebar bag. Reserve it for small items you use frequently or need to find easily. Our handlebar bags carry cam era gear, glasses, sunscreen, lip cream, wallet, notebook, pencil, handkerchief, snack food, frequently used tools and any other personal necessities. Once your handlebar bag gear is separated, weigh it with the bag — then weigh your remaining gear. The front load should be approximately 20-30 percent of your total gear load. Do some juggling if necessary to stay within this range. If you are using front panniers, try different equipment up front until you arrive at the best weight for the handling qualities of your own bicycle.

Remaining gear goes into the rear panniers. First decide on what you want and need in any outside pockets. These are things you need to get to often or fast such as extra water, lock and cable, rain gear, extra food (snack or lunch), and perhaps a jacket. When loading the main compartment, keep heavy items on the bottom. Tools, stove, cooking gear, air mattress and staple foods are best here. Put lighter items such as clothing and toilet articles on top.

Pack each pannier set (front or rear) evenly. One side should be within one or two pounds of the other for best- possible riding characteristics. Once you have an evenly spaced load, maintain it — and your sanity while on the road — by always putting everything back the same way each time you load up. If you do this initial packing at home with access to a scale, and then stick to your arrangement while on the road, you ease your passage as well as insure a smooth-handling loaded touring bike.

Once the panniers and handlebar bag are full, it’s time to strap on the sleeping bag, tent and sleeping pad. These travel best sideways across the top of the rear rack if your panniers permit this arrangement. With front panniers and rack a small tent or sleeping bag can travel up front, but usually everything in this category goes to the rear. Put the heaviest item forward next to the seatpost, being very careful that it does not interfere with the rear brake even if the load shifts. Shift the load as far forward as possible since a heavy load to the rear can cause fishtailing.

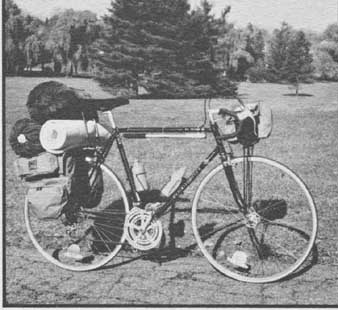

ABOVE: A good example of a poorly loaded touring bike with too much weight

for back, oversize equipment and panniers too far behind axles. Straps are

a more secure tie-down than Bungee cords.

Elastic stretch (Bungee) cords are popular tie-downs but we don’t like them. Sometimes these cords are not stretched enough to put adequate pres sure on the load or to keep them from coming unhooked. If they do come loose or one time you forget to hook them, the hook will grab onto the spokes. Then you have real problems. Many accidents occur on loaded touring bicycles when objects become en tangled in the wheels. We prefer 3/4 or 1-inch nylon straps with secure buck les. Use the kind that can be adjusted for length, fasten them securely, and you won’t have to worry about shifting loads or spoke entanglement. Interlace the straps (two or three) through the rack platform and on either side, place your baggage on the rack, then cinch it all down firmly.

When everything is carefully and thoughtfully loaded on your bike, check all attachments one more time before taking off on a trial run. Riding a fully loaded touring bike is a lot different from jamming around unloaded. It takes you longer to start and stop, not to mention the extra instability due to the heavier, higher load. Go slow to get the feel of things, staying out of traffic or other scary situations. Ride as much as possible with your bike fully loaded before setting out on a long tour. You will be doing your body a favor and you will have time to correct any problems be fore you get away from home.

Plan ahead, allow yourself plenty of practice time, and the day will soon come when you roll out of your drive way completely self-contained, self-propelled and self-confident. There is nothing between you and the world but miles.