The best place to begin bicycle touring is at your own front door. You can start today. Pack a little food, fill your water bottle, check your bike and head out. Where? Does it matter? OK, that is a little unfair. To some it matters, but to others.

To us, the archetypal cycle tourist is one who cycles purely for pleasure, for the experience itself. There are no goals, no restrictions, no reservations, no time schedules. If a philosophy exists at all, it’s that it’s better to travel than to arrive. The means and the end become one. Impossible in this world of clocks and fences, tickets and timetables? Perhaps. But a bicycle is a very good vehicle for easing through the barriers that we build around ourselves. You can only go at a limited speed; you are subject to every whim, whiff and wayside attraction; you have every excuse in the world to totally flow in the “now” of experience.

If you can, give yourself a chunk of time and try a non-destination bicycle tour. Pick a direction and set out. In most areas of the country there are campgrounds, towns and motels in which you can pass a night without advance notice after you have put enough miles in for the day. In spite of our seemingly innate need for routine and structure, you can cater to the craving for adventure in your nature simply by cycling out of your confines on a bicycle — if only for a weekend.

As ideal as this may seem, it’s not everyone’s idea of a good time. It assumes a certain expertise on wheels, a familiarity with touring and tripping that you may not feel you have at this point. So how else does one begin touring by bicycle?

It’s best to start slow and gradually build toward your personal touring goal, whether that is to go overnight to a nearby park with the family or to try for a coast-to-coast summer on wheels. Naturally, we advocate building up physically, dealt with more extensively in Section twelve, but you must also build up psychologically for touring. This is especially true if you are easing a reluctant spouse or friend into cycling and cycle touring. You need to build on positive experiences; frequently the most positive experiences of our lives are the small ones, the little things that may not have seemed at the time like an “experience” at all.

Initially, if you have not yet cycled distances, you need to learn that a bicycle will truly get you from here to there and back again. Ten miles in one day may seem mind boggling at first; it did to Don when she began. And it is. But the next time is easier, with each ride bringing greater distances within the scope of possibility.

Begin with day tours. Pack a lunch or pick a distant, favorite restaurant and spend the day on your bike. If there is a cycling club in your area, join the club members on shorter rides — don’t pick a 50-miler if you are just beginning. Trying to keep up with the Joneses is the best way to end up hating your bicycle.

Most clubs have beginner rides; if not, have your own. Is there a favorite area near your home? A museum, theater, park, zoo or simply a scenic view? Pick a relative or friend you enjoy visiting.

The important thing is to get there and back again by bicycle.

Increase the amount of time you spend on your bike for each day trip. As your cadence and riding style improve, your range will extend, opening new possibilities of pleasure.

At some point you will resent turning homeward midway through your day. The hills or fields or sights of the city will beckon and you will wish you could cycle the whole weekend instead of a single day. It’s time to plan your first overnighter.

By now you know how far you can comfortably travel in one day. Plan your first overnight tour for around that distance. Don’t give into the temptation to exceed your maximum distance to date. Remember, you must be able to get out of bed and do the same thing the next day, hopefully with a smile on your face. If you have done 35 miles in a day, try an overnight round trip of 60 miles. You will no doubt feel like going farther the first day; adrenalin works muscular wonders but it has a way of deserting you overnight. Resist the temptation, lie down on the grass until it goes away if need be. The best time to determine how far you should go the first day is at the end of the second day.

On your first overnighter, treat yourself to a motel, a hostel, or some soft place to land. Your equipment needs are then minimal yet you have maximum comfort at the end of the day. Many reluctant riders have been hooked on cycling because a considerate companion smoothed the rough edges off a first tour. A credit card is the lightest piece of touring equipment yet developed. If you possess one and are not averse to using it, why not let it ease your entry into the wide world of bicycle touring?

You can keep your baggage needs lower by eating out. If you can’t afford it or can’t hack the state of American culinary art, either take along or buy your food at a market at the end of the day. Meals are easy with cold foods or supermarket deli specials on paper plates. As soon as you feel comfortable and competent putting any number of miles under your seat on a two-day tour, be gin carrying whatever gear you desire for fun, food and fulfillment. If camping is your idea of heaven, go at it with tents, panniers and Primus stove (see Section nine). If city life is your bag, pack an evening gown or tux and cycle to a downtown hotel for an evening at the theater. Have to attend a family re union 50 miles away? Get there by bike. You will find things to talk about with relatives you never knew you had any thing in common with, or you might simply confirm their already “iffy” opinion of you. Either way, it will liven up your visit. Your weekend touring possibilities are only as limited as your imagination.

Frequently, the best weekend tours begin at your doorstep. The less you involve other modes of transportation, the more time you have for the pleasures of cycling. If you can plan circular trips with a minimum of backtracking, so much the better. The only guide you need for this type of tour is the basic automobile road map. If you live in a major metropolitan area, there is probably a bicycle-touring guide guide that outlines day and weekend trips. Many regions and states have such guides; ask at your local bicycle shop, guide store or library. Check with your local bike club for good trips, or join them on rides in your area. Some state automobile clubs have bicycle-touring guides; if not, the local office should have knowledgeable people who are familiar with the surrounding area and could suggest possible routes. At the least, auto clubs have high-quality road maps. County maps are frequently the best for detail, yet cover enough area to keep you cycling in circles for weeks or months of mini-trips. If you aren’t already a member of an auto club, consider joining one. Sometimes the maps, tour books and camping guides alone are worth the membership cost, even if you don’t own a car. As a cyclist you share the same roads, enjoying both the rights and responsibilities of a motor vehicle.

Sooner or later we hope you find yourself with a chunk of time and the inclination to cycle somewhere far, far away. This might be a 400-mile trip through your state that begins right at your door, or it might mean a transport somewhere for two weeks of cycling in a totally different area. Try Utah in the spring, southern Arizona or Hawaii in the winter, New England in the fall, or how does an Alaskan cycling summer sound? How far can you cycle in how long? You probably know your “comfort range” by now, but a safe average to plan on is 50 miles a day when fully loaded; 60-80 miles with a minimum of gear or with more touring experience.

Knowing how far you can go in a day, plus the known amount of time you have available, you can sit down with a map and gain a realistic idea as to what the world offers you and your bicycle. Now the fun begins. As we said, the best touring begins at your doorstep. Better yet, it can begin in your living- room easy chair right now. Pick up a map, lean back and follow us.

Route Selection

You must first decide where you want to go. The safest, fastest, easiest route in the world is no good whatsoever if it’s not where you want to be.

Once your ultimate destination is decided, then you can begin to plot out the best route to or through it. By best we mean limited traffic, paved shoulders, small gradients, predominant tail winds; all those things that seem to smooth the road so you can enjoy the aesthetics of the area.

Trying to find all of those elements in one route is at best extremely difficult. But you should have them in mind as you select one road over another. Most rural secondary roads offer the least traffic unless they pass through recognized vacation areas. The most unlikely roads can be unbelievably congested on weekends until you discover that a good fishing lake is nearby. Hunting season can do terrible things to an otherwise deserted road. Look for major roads or interstate highways that drain the majority of traffic from secondary roads nearby. In an earlier day, these smaller roads were direct routes into and through an area; they are ideal for cycling.

When selecting routes we frequently opt for off-the-beaten-path areas that most tourists bypass. Many motor tourists drive directly from one resort area or scenic attraction to the next. We usually note where those areas are and try hard to skirt around them. Our policy is to stay away from popular attractions and concentrate on quieter, more secluded countryside where the cycle tourist has a chance to experience the totality of the environment in a leisurely, personal manner. The Grand Canyon is awe inspiring no matter how you get there. But it takes a bicycle to really experience the tiny Mormon settlements of southern Utah, the vast expanses of a ranch in Wyoming or the small seaports of Maine.

Where to Stay

Whether you are just taking mini tours or you are planning a big one, you want each night’s stay to have as little fuss as possible. If you don’t camp, your choices are pretty well limited to private homes, motels or hostels. Private homes are up to you to find and treasure, unless you can take advantage of the system of private homes that serve as “tourist inns” offering economical lodging and sometimes meals. This is worth asking about in towns you pass through, especially in the central and eastern United States.

Motels offer a sometimes expensive, yet very available nationwide accommodation alternative. There are numerous state and nationwide chains that you can contact for advanced reservations, sometimes toll free from your home phone. Of course, you must then stick to your planned cycling schedule, something hard to do given the delights and distresses of bicycling. If you are not sure of your distance capabilities or would like to wander without restriction, there are usually older independent motels and hotels where reservations are seldom necessary. We have found these to be generally inexpensive if we are willing to forgo swimming pools, saunas and free ice.

When stopping at a motel, give yourself time to cool off before entering. Take off your helmet and rearview mirror (best done out of view of the office), and run a comb through your hair. We have been refused lodging only once due to our cycling appearance, but others — especially lone males — report problems more frequently. Sure, as long as you can pay the tariff, appearance shouldn’t count, but to many people it still makes the difference between the good guys and the bad guys. Always present yourself in the best possible light and explain as soon as feasible that you are bicycle touring (not cycle touring). They may think you’re crazy, but at least not malicious or dangerous. We never ask ahead about taking our bikes and gear into the motel room; we do it as a matter of course. We have yet to run into any trouble, even at major hotels, but we do opt for unobtrusive entries and out-of-sight elevators when ever possible.

For lodging somewhere between the minimal expense of camping and the maximum expense of “moteling”, hostels are the answer. Most hostels pro vide dormitory-style sleeping accommodations usually with blankets, cooking facilities and sometimes showers provided. Costs run $1-$4 per night, with chores occasionally required in addition to the fee. Hostels were originally intended for traveling students, but adults are welcomed in most countries of the world. A membership card is required and may be obtained for a small fee from American Youth Hostels, Inc., National Campus, Delaplane, VA 22025; it’s accepted all over the world.

In Europe, youth hostels are found everywhere; daily cycling between them is easy. In the United States there are only about 200 hostels, mostly situated in the Northeast. It’s possible to tour using hostels for all of your accommodations, but this gets tricky for extended touring. Every year legislation is introduced into Congress to subsidize the building of more hostels, but it has not yet been passed.

Meeting nice people is one of the nicest things about staying in hostels. It’s perhaps the quickest way to learn the ins and outs of inexpensive travel. Hostels are a great medium for fostering international understanding and friendships; we highly recommend them for your use.

Maps – Print, Google-Maps, MapQuest, Smartphone

Planning your long-distance tour can be almost as much fun as doing it. You can begin as soon as you decide where you want to go. If you are not familiar with an area, or even if you want only to update your information, there is a huge amount of material available to you. The best place to begin is with maps.

Maps are to the bicycle tourist what recipes are to the cook. Good ones are full of general and specialized information just waiting to be discovered. Most people read a map; maps really come into their own when they are interpreted. A good text for developing your map-reading skills is Mapping by David Greenhood, but you will find that maps bend to your will if you simply ask the right questions and take the time to find the answers.

Maps are basically representations of the earth’s surface on a flat piece of paper. There are specialized maps of just about any phenomenon, but the better automobile road maps are adequate for most cycling purposes. Topographic maps, those showing relief (the ups and downs of the land) using con tour lines, can be useful but are by no means necessary. Although they show many cultural features such as roads and towns, they are not as up to date as most road maps. Good coverage with topographic maps on a long tour would mean a big expenditure and a storage problem due to the size and number of maps that would be involved.

If you want to use them for shorter tours, they are available at many back packing stores or directly from the government. Request an index for your state, pick out the specific maps you need, then order them at a cost of $1.25-$2.00 each depending on the scale. If you live east of the Mississippi write: Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geo logical Survey, 1200 South Eads Street, Arlington, VA 22202. If you live west of the Mississippi write: Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey, Box 25286, Federal Center, Denver, CO 80225.

Good local and county maps are available from bookstores and, of course, on your cell phone. Rand McNally has excellent state maps. Many gas stations now charge for maps but they are still a bar gain. State-supplied road maps are usually of poor quality. For Europe, the Michelin 1:200,000 series is excellent as are Bartholomew’s maps of the United Kingdom. In the United States, Michelin’s maps are available at PO Box 5022, The Bicycle Touring Guide New Hyde Park, NY 11040; Bartholo mew’s maps from the American Map Company, 1926 Broadway, New York, NY 10023.

Any of the better maps will show you the current road situation, but they also contain many cultural and physical features. Some are shaded to indicate major physical relief. Elevation is the distance of a point above sea level; relief is the local difference in topography (how much one point is above or below another). An area may be 7,000 feet in elevation yet relatively flat with little relief, such as a high plain or plateau. Conversely, a road might parallel the coast at only 100 feet average elevation, yet that road may be very hilly with steep gradients due to rugged relief.

General relief can be interpreted from unshaded road maps if you look closely at available data. Town elevations and passes are usually marked, or town elevations can be found on the back of the map in the index section. If town A is 1,050 feet and town B is 1,330 feet with a 4,000-foot pass in between, then you can figure on some pretty hard pedaling to the pass and a nice, long downhill to town B. This is general and not to be read as absolute reality, but it does give an indication of what is in store for you on a particular road. If you want to know if a stretch of road is uphill or downhill, check for a stream or river flowing beside it. Follow the stream until you can determine its point of origin or exit, then you can determine the nature of the road. By looking closely you can tell a little about the lay of the land by stream patterns. Short, relatively straight streams can mean steep, rugged topography; long, winding streams usually indicate gentle valleys.

Using these clues along with your general knowledge of an area, you can make good decisions about what you can expect in any given region and what routes to choose. Maps provide an excess of information; it’s up to you to ask the right questions and interpret the data on the map for the answers.

Maps tell you much more than physical and road information. The cultural data is sometimes of greater importance to the touring cyclist. The population of a town according to the latest census not only satisfies your curiosity but gives you a valuable clue as to the services you might expect to find there. A village of 400 may not have a grocery store, but a town of 3,000 surely does. With some road experience you will even be able to make an educated guess as to whether a store would be open on Sunday. (Very likely in a town of 3,000, if there are no really large towns nearby.) With practice you will be able to predict fairly accurately if ser vices and facilities are available; be aware however, that customs vary in different states or even in differing ethnic areas within the same state. In some sections of the country, markets never seem to close; in others, 6:00 P.M. is the absolute end of the business day. In one area, stores may close on Mondays and remain open on the weekend; in others, Sunday is the observed non business day. Be flexible and always carry emergency rations.

Most good road maps show public campgrounds; some even show private ones, but we have found it best to supplement this information with camp ground guides published by map companies, travel trailer groups and auto clubs. In the West it’s particularly important to know whether camp grounds provide water; the guides tell you this, road maps do not. Many public campgrounds are located in national forests, which are usually shown as green shaded areas on road maps. These areas usually mean trees, and in the West trees mean higher elevation with improved scenery; clues important to the cycle tourist in planning a route.

Roadside rests are another feature shown on good road maps. In some states these are no more than a trash can or table; in others they might mean running water, flush toilets, phones and even overnight camping. When planning critical aspects of your tour such as water-supply points and overnight stops, don’t rely on a single map source, no matter how good it is. On their road maps, Arizona and California use the same symbol for roadside rests. California interstates provide full service at these with water, making bicycle touring possible in large areas of desert where it would otherwise be difficult if not risky. However, when the tourist enters Arizona conditions change radically. There, roadside rests can be very primitive with no water available. The cyclist cannot make assumptions when it comes to important things like water. He should use more than one source of information.

Road maps frequently designate scenic routes. When venturing into new areas notice the best of the region by planning your trip along such routes. Be aware, however, that some of these might be heavily trafficked, especially on weekends and during peak summer months. Off-season and during the week these routes can be delightfully lonely.

In addition to being critical to plan- fling and carrying out your tour, maps offer unlimited hours of enjoyment, relaxation and education to the armchair portion of your tour. Every good tour consists of three definable segments: the preparation, the actual tour and the memories of it all. Maps are important to all three. If you are using your map only for the actual tour, you are missing out on two-thirds of the pleasure. If you are like us, you will never be able to realize all of your touring ambitions, but that doesn’t stop us from enjoying many tours vicariously by selecting a route and traveling it from the softness of our living room using pretend wheels over paper roads. Whether you are actually planning a trip or just taking a magical mystery tour you will be sharpening your map skills and broadening one very real aspect of the bicycle touring experience. No one is born with map reading skills.

As hard as it’s for us to imagine, not everyone loves maps or feels comfortable trying to unlock their secrets. It’s certainly easier and may even be necessary for you to follow someone else’s route. They are available, planned in de tail down to each rest stop, along well- thought-out, safe (hopefully) routes, through towns willingly playing host to many cyclists. Traveling that way relieves you of much of the responsibility and a lot of the advance planning of a bike tour. Beware. It can also rob you of the joy of complete independence, of charting your own way in the world, of getting where only you want to go, and perhaps of your being the only one who happens along that way.

Gathering Information

You will need and want more information about an extended tour destination than is available on road maps alone. If you are totally unfamiliar with an area, anything can help give you in sight. A lot of advance information may seem superfluous when it comes to actual planning, but it can add appreciably to your enjoyment on tour, sharpening your view so that you can look deeper into an area because you are already familiar with surface things.

Allow yourself time to write for in formation that might not be readily avail able to you. Whenever you write, be specific about what you want to know and where you are going to be touring. Make it as easy as possible for the informant to answer you, even to listing questions that can be checked yes or no, or at least answered very briefly on your same sheet of paper. We were deluged with requests for information following the publication in Bicycling magazine of articles on our cross-country trip. Most were broad requests for information, some wanting us to “tell anything you know” about bike touring or a specific route. Tim’s article “Four Across America: Afterwards” in the May 1978 issue was in partial reply to these requests; this guide will have to take care of the rest. Obviously, we weren’t able to write the amount of information requested in one reply. When you ask for information, be specific.

Most countries in the world and each state in the United States has a department of tourism. You may contact it through the U.S. consul or state capital to request information on a specific region. You will usually be deluged in re turn with loads of information on cultural and scenic attractions. De scribe exactly or as closely as possible where you will be touring and ask for any other information they might have on that particular area. Be sure to mention in your request that you are bicycle touring.

Other sources to approach in writing are the chambers of commerce in towns along your route. Write directly to the chamber of commerce addressed to the town (using zip codes) and it will get to the right people. If you ask specifically about accommodations and services, you will sometimes get detailed lists including lodging prices. Many towns have climate charts that can help you to decide when you would prefer to tour and the sort of clothing and equipment you will need. If you want, ask the chamber of commerce to include an issue of the local paper.

More information is available in general and regional tour books from your local library. Let the librarian in on your plans and you will have access to a vast amount of information you probably never dreamed existed. Many large libraries have newspapers from various regions around the United States, some have international periodicals as well. These are good for the type of information we discussed, which gives you a feeling of familiarity in advance so you can use your touring time to really get into the more unknown aspects of an area.

Also at the library, again the larger ones, is perhaps the greatest single source of really important information for the bicycle tourist in the United States. This is the National Atlas of the United States. The amount of information that can be gleaned from its pages is astounding. Plan several hours to pour over it; be sure to have a note guide for jotting down important data. It’s fairly large and it’s difficult to photo copy selected pages, but not impossible. This guide is available from the U.S.

Government Printing Office (see address below) for the sum of $100; better hope your local library has it.

The National Atlas of the United States has maps of just about every mappable phenomenon in this country from air pollution to public lands to wind direction. Anyone anticipating an extensive tour in this country should be aware of this source of information. The map of prevailing wind direction is of particular interest, since wind is one of the major weather elements that affects your tour. There is nothing worse than gearing down to struggle along on a level or even downhill section because of a strong head wind. Day after day of fighting head winds can be the most de moralizing part of any tour. You can’t do anything about them, but you can at tempt to plan your tours around known prevailing winds. That is why most cross-country tours are planned from west to east, also why most West Coast tours start in the north and proceed south. Using the wind direction maps in the National Atlas will give you an idea as to “normal” wind patterns. Don’t be too shocked, however, if you happen to encounter abnormal winds while touring; it happens all too often.

Weather Information

In addition to the National Atlas, there are more specific sources of weather information for the entire United States that are of value to the cycle tourist. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration puts out a series of pamphlets entitled Climates of the States. In theory there is one for every state but some are out of print. Write the U.S. Government Printing Office, Cap Street, Washington, DC 20402 for the state or states you want (about $1 each). If you live near a major college or university, its library should have a government publications section where you can look at and reproduce what you want. The Climates of the States pamphlets give you specific data on high and low temperatures, precipitation and frost-free periods for climate stations around each state as well as detailed information for selected stations in the state. There is a synopsis for the entire state with a breakdown of climatic regions within it. If you use these pamphlets you will have no excuse for not knowing what to expect climate- wise where you are touring. They are only describing climate, the long-term trends in atmospheric condition, not the weather, which is the daily mixture of elements through which you will be riding. Weather and climate can vary drastically, but you will at least have a guide as to what is probable.

If your touring is limited to one specific area, write for “Local Climatological Data,” available through the National Climate Center, Federal Building, Asheville, NC 28801. For a small fee (20c the center will send you a climatic data sheet for almost any town or city in the United States. Each sheet gives you specific information on temperature, precipitation, wind direction, percentage of sunshine, record highs and lows, amounts of snow, rain, hail and humidity. Simply request the sheet(s) for the town or city you are interested in. Great for the planning stage of a tour, these sheets give hours of enjoyment to the armchair tourer as well.

Road Conditions

As you gather data on scenic wonders and possibilities of sunshine, you might also obtain what advance information is available about road conditions — shoulders, traffic hazards, gradients, and perhaps large-scale construction projects — that might detour or detain you. If you have settled on a specific tour and route, with leeway for the inviting and the unforeseen, there really isn’t a whole lot you can do about road conditions. But like the weather, it’s good to know the possibilities. The best, single source of road information is the state’s highway department. Some states have a centralized data- gathering department, others handle it on a regional or county basis. Phone or write your local office and ask how you can acquire traffic flow, gradient and road shoulder information. If they can’t help, then ask for the address of the state office. Most states have specific information on road conditions that is valuable to the cycle tourist, but many charge for the data. Some states, like Washington and California, have an office just for providing information to bicycle travelers on routes and road conditions. Ask the states you are interested in for any information specifically on bicycling in their state. Whatever you do, don’t ask for road information on the whole state. Decide beforehand what roads you most likely will be traveling, then ask about those routes and any alternative routes they might suggest. Also, ask about any planned construction or repair projects on your route L during the period you will be touring. Bi cycling over wet tar behind motor homes and trailers is no fun.

Wide paved shoulders are a cyclist’s dream. They can also be frustratingly rare or intermittent for un explained reasons. You may be better off trusting to luck and taking what you get. In some states, almost all primary and secondary roads have some sort of paved margin to the side. Even if only a foot or two, it’s important to the cyclist — not as a steady path, but as an escape hatch when traffic pressures dictate. Many roads are only two lanes on which the cyclist has as much right as a vehicle. Unfortunately the typical American motorist does not always agree, even though it’s the law.

Somehow, sharing the road with a cyclist is a blow to the ego of many drivers, especially if they have to pull out of their lanes to pass. Even if there are no cars approaching in the opposite direction, many drivers won’t pull out to give the bicycle a few extra feet. In other areas of the world, it’s an accepted practice to pass cyclists as one would any other slow-moving vehicle on the road. While riding in Mexico we were pleasantly surprised that the Mexi can driver almost always moves over to the opposite side of the road when passing a cyclist. However, when American tourists came along they seldom did the same, and instead inched by dangerously close and frequently forced us off onto the dirt path at the side of the road.

Time after time on our cross-country trip we were passed dangerously close by motorists who refused to slow down as they approached us in the lane, even though they could see us and our Buggers far ahead and could also see that we had no shoulder on which to pull off. Many times we were passed on blind curves or on “no passing” sections of hills, simply because drivers would not slow down and ob serve the legal method of passing an other vehicle, evidently because we were on bicycles. Tractors and horse- pulled wagons get more road courtesy than the cyclist.

Lack of shoulders on lightly traveled roads is not a tour-stopping problem. We have traveled thousands of miles on two-lane roads, and many of those miles have been the most pleas ant we have known. There are dangers however. The ignorant, in-a-hurry motorist is one. Another is the recreational vehicle looming up behind you on that narrow road with its mirrors extending two feet into your backside, or even worse, you see it approaching blithely from the rear with its metal steps dangling dangerously out from beneath the door. That is the time to abandon the road. Take their license number if it makes you feel better — although it won’t do much good unless the protrusions put them beyond the legal eight- foot width requirement — but don’t decide that this is the time to lay claim to your piece of road. You may get six feet of ground out of it, but not pavement. On heavily traveled tourist routes with limited or no shoulders (such as California’s coastal Highway 1) the bicyclist is at the mercy of RV drivers who are sometimes inexperienced and unaware of the danger they represent for cyclists. Use your rearview mirror constantly and keep an escape route in mind.

Recent passage of federal legislation allows highway funds to be used for bikeway construction, which now includes the widening or paving of road shoulders. If all states would pave just two feet of shoulder on all their roads, think what a boon to bicycle touring that would be. Maybe someday …. Until then, you can write to the state department of highways to ascertain where paved shoulders exist if you want to limit your touring to those roads. Other wise, take what you get, keep your ears and eyes open, and help make states aware of the need for paved shoulders.

You may want to take road gradients into consideration when planning your tour. An all-flat tour might be easy, but it might be boring too. Road maps give you some indication of the terrain, using the clues of elevation and stream- flow we mentioned. If you want more detailed information about a specific route, the state highway department might be able to help you. When we tour we try only to avoid the steepest passes if possible. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking that all passes must be circumnavigated. Some of the finest country is found at high elevations; you will miss a lot if you don’t attempt a big one now and then. Mountains can be deceiving. We found crossing the Rockies through an 11,000-feet pass more enjoyable than passing through the Appalachians over a seemingly endless series of 3,000-feet passes. It’s all relative to your outlook and whether you are where you want to be or just on the way there.

- Getting to Your Jumping-Off Place -

Although the ideal is to tour from your front door and back again, we realize that it’s not always possible or desirable. Perhaps second best is to drive your car to a safe place (such as a 24- hour service station, police station or ranger station), then pedal off to return by a circular route or public transportation from the termination point of your tour. All you really need is a secure means of carrying your bicycle on your vehicle and the will to put some time in behind the wheel before you can put some time in on your wheels.

If you don’t have a car or time and distance negate its use, public transportation will have to get you where you want to tour. The transportation of bicycles via public conveyances in the United States is in a continual state of flux and uncertainty. Due to rapid changes in policy and price, we can only give you hints and guidelines, leaving final arrangements and details to you. Always check the regulations and procedures of public carriers with at least two employees of the company you are dealing with, preferably at least a day apart. Take names and numbers when someone tells you something so that you have at least that much to back you up if things are not as they should be when you reach your destination.

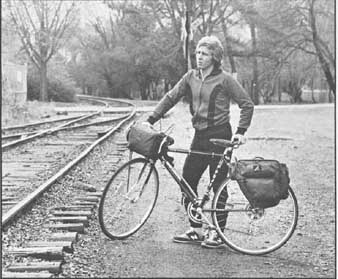

above: Many cyclists find the train (Amtrak, etc.) a very convenient way to get

to the starting point for a tour.

The train seems to be the best public transport available for bicycles now in the United States, and in Europe too. Train travel is sometimes comparable to the cost of similar bus transport and, more important, your bicycle is usually handled with less hassle and greater care. Unlike Europe, the United States has limited passenger-train service now, with probably even more restricted travel in the future. When planning rail transport to your jumping-off place, make sure at the beginning that there is passenger service available there; many routes are freight only. Get a copy of Amtrak’s (National Railroad Passenger Corporation) national timetable, which includes a map of its service-including stops. Write to Po Box 2709, Washington, DC 20001. If you know specifically where you are going, call Amtrak’s toll-free number (in your phone guide or ask information) to check on service and timetables. Be sure to verify that your bike can be loaded or unloaded at that point. Amtrak has many stops where freight cannot be handled due to lack of baggage-handling facilities and personnel. Unless you find out absolutely, you may find yourself standing at Podunk Station, U.S.A., while your bike passes on another 200 miles to Bigville. Some times freight can be loaded or unloaded only on certain runs. Know where your bike is so you don’t have any surprise eight-hour waits for another train.

Amtrak now requires the boxing of all bikes. Because of changes in Amtrak requirements, we advise you to check with them before traveling. Amtrak sells boxes for $4 at its major urban stations. There is also a $5 handling charge for all bikes.

If you plan to box your bike, call ahead to the station to insure that boxes are available or get your own from a bike store. Plan to arrive at the station at least an hour early so you can remove your pedals, lower the seatpost and turn the handlebars for boxing. Be sure you have both the tools and the know-how to do this. (Loosen your pedals before you leave home. Few tourists carry a 12- inch pedal wrench in case you can’t break them loose at the station.) If you aren’t boxing your bike, still plan to arrive at least 30 minutes ahead of departure. Baggage clerks are notoriously inflexible about receiving bicycles late; be nice to them and they will be more likely to be nice to your bike.

If you are returning to the same jumping-off point, don’t count on Amtrak — or any other public carrier for that matter — to store your box for you. It’s your box and they figure it’s your problem. This all sounds pretty bad; certainly it’s worse than in Europe where people have been hauling bikes around for decades. Protect yourself by planning ahead, checking and double- checking all steps where you are relying on someone or something else.

Have enough cash for any unexpected delays, be flexible and smile a lot.

Buses are another way of getting there with your bike. In the United States and Latin America buses run just about everywhere at one time or another. The cost is usually low, but your bike must be boxed or covered in an acceptable manner so as not to damage other baggage. Bus baggage compartments are more restrictive than trains, so make sure you box it well. Put a block of wood between the fork blades to insure that they don’t get com pressed. The box has to be smaller than those for trains and planes; use the bike-shop kind, which requires removal of the front wheel. All this takes time and a knowledge of what you are doing and how you can undo it when you want to put it all back together again. Check with the bus company for exact size restrictions so you are sure that the box you use is right, but many times bikes are excused from size regulations.

We have heard that bike boxes will fit standing upright in Continental Trail- ways bus baggage compartments. On Greyhound the box has to lie flat on its side, usually under all the other luggage. Be there when your bike (box) is loaded so you can attempt some control over the process (suggest nicely that it go in upright if possible and please don’t put the box of rattling liquor bottles on top of it). Also make sure your bike changes buses whenever you do.

Airplanes are the fastest and most expensive means of getting you and your bike on tour. Within the United States, most airlines allow you to take your bike along for about $10; most also insist on it being boxed. Some carriers have large boxes that don’t require removal of the front wheel; there is usually a charge for these. Always check with at least two airline employees, including one at the airport itself, to insure that a box is available when and where you need it. There is nothing worse than getting to the airport only to find that they just gave out the last box. Make sure you have the tools accessible to box your bike and leave yourself plenty of time to do it right.

On international flights, regulations regarding bicycles are varied and changing all the time. Most certainly, however, your bike will have to be boxed in the smaller bike-shop-type carton, or in some sort of specialized bag. On some international carriers your bike goes as part of your weight allowance, on others you pay an excess weight fee even if your baggage total is •not in excess. Sometimes the same carrier will charge you one time, but not the next. Confusion reigns. Keep your bike and baggage below the maximum weight allowed if possible and if you care. This can sometimes be assured by wearing your heaviest clothing and carrying tools and cooking gear in your carry-on luggage. Pack your bike in the smallest possible box, smile a lot, and hope for an understanding person at the check-in counter. You have of course checked regulations and know who told you what if a problem arises.

When you first make your plans to use public transportation, call around, check carefully and travel the line that is most sympathetic to your needs as a bicycle tourist. It won’t hurt to let them know that that is why you are traveling with them instead of with a competitor. Smooth the way for the next cyclist.

No matter how you get to your jumping-off point, there is real joy in un loading your bike, attaching your gear, and pedaling off self-contained and self-propelled while others hassle with suitcases, taxis, schedules and reservations. Point your wheels in the direction you want to go and head out. Such in dependence and self-sufficiency in a complex and frustrating world are two of the primary advantages of bicycle touring. If you have your sleeping bag and cooking gear on behind as well, you are even that much further ahead on your way to cycling pleasure.

above: Boxed bicycle, ready for transport.