Imagine yourself already on the road, let’s say 14 days into a month-long tour of the backcountry of Utah and western Colorado. You are touring alone, camping along the way with occasional stops in motels, completely self-contained with your camping and touring gear in rear panniers and a handlebar bag.

The buzz of your alarm (travel clock or wristwatch) shatters the silence of your still-dark tent; you turn it oft, groaning at the 4:30 A.M. hour. Just as you settle back into your sleeping bag for 40 winks, you remember where you are and why you must be on the road so early. It’s the last of the desert but temperatures for this July day are predicted to reach 100°F. You have many miles to go before that happens, a lot of them in the higher elevations and steeper roads of the western Rockies. Adrenalin sends you out of your bag, bike light in hand, to search for your clothes. As you feel the cool morning air of the high desert just before leaving the tent, you grab your warm-up jacket.

Emerging into the predawn darkness, you pull out your sleeping bag and lay it over the top of the tent to air in the low humidity of the desert. You re member tours in the Midwest and East where you had to air it inside the tent because everything outside was soaked with dew. This brings your first smile of the day and renews your love of desert touring.

Breakfast begins with a bowl of cereal moistened with powdered milk or the last of the fresh milk you purchased the night before. A slice of whole wheat bread spread with peanut butter is either topped with or accompanied by a banana, the last of several you bought at a fruit stand two days ago. You make a mental note to buy more this evening. You decide against starting up the pres sure stove for your usual cup of hot herb tea with honey due to the rapidly increasing color in the eastern horizon.

You watch the few, temporary clouds turn from deep purple to pink with silver trim as the still-sunken sun begins its influence on your half of the world. The morning silence is punctured by the chirping of a cricket nearby and the distant, soft hooting of an owl as he turns loose of the night so your day can begin. You break the moment to gather your cup, spoon and knife — the only dishes to clean after your simple breakfast.

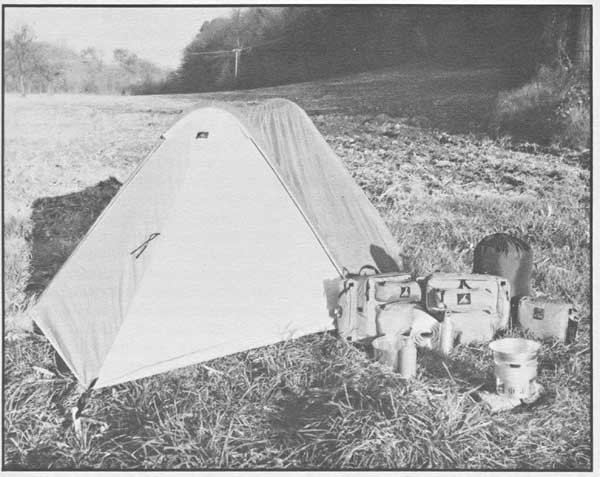

ABOVE: One of the biggest rewards of bicycle touring is your ability to be independent

and self-sufficient. All the supplies at this typical campsite can be readily

loaded aboard the bike and transported as far as you care to go.

Once in motion, you put away your kitchenware, stuff the now-dry sleeping bag into its sack and roll up your sleeping pad. While inside the tent, you gather up the paraphernalia of the night — map, book, light, watch and extra water bottle. Once the loaded panniers are outside the tent, you sweep it out, drop it and roll it up. The ground cloth needs to be shaken and turned over a bush to dry; even in the desert it picks up moisture from the ground, blocking it from entry through the tent floor. At this point you welcome the call of nature. You grab your trowel and toilet paper, going off to find a spot that is no good for any thing else (not in the middle of a potential campsite, picnic area or trail). After making use of the 6- to 12-inch hole you dug, you cover it with the original dirt and place a good-size rock on top to discourage re-excavation by desert animals.

On returning to camp, it’s time to check your bike for the day’s journey before loading it up with gear. After checking the tire pressure with your gauge, you pinch the spokes in pairs all around to check for loose ones, then spin each wheel while observing its passage past the brake pads to check for trueness. Finally, you run your fingers lightly over the tires for imbedded objects and check the functioning of the brakes.

By now the ground cloth should be dry (if not, fold the wet side into itself) so it can be folded and slipped into the tent bag along with the stakes, brush, fly and tent itself. After checking around for loose items, you hook the panniers and handlebar bag to your bike, making sure everything is snug and properly hooked. You strap the tent, sleeping bag and pad on top of the load, again taking care that everything is well cinched down with no loose ends. Then you put the snack food for the day into the handlebar bag for easy access. After filling your water bottles from the folding water jug, you strap it across the top of the load on the rear rack, noting that there is only about a half-gallon left. Since there is a town about 35 miles ahead, you are not concerned. This should be your last “dry” camp as you will be in the mountains tonight.

One last look around camp reveals yesterday’s socks hanging on a bush; you spook a white-footed mouse as you grab them and stuff them into your panniers. It’s a good thing you can get into them easily even with everything al ready loaded on top. The mouse eyes you suspiciously from under another bush as you begin a few stretching and twisting exercises. You have completely lost the stiffness and aches of the first week out, and your body quickly responds to your exercise routine. Warmed up, you walk your bike back along the almost invisible dirt trail you followed about ¼ mile from the highway around a small hill to the quiet, secluded spot where you spent the night. Out of sight from the road, you were careful not to camp in the wash just a little farther on. Dry now, its steep banks attest to the torrents of water that have poured down it in past flash floods. It could flood even though not a drop of rain is falling for miles around. It drains a small range of mountains in the distance; a good rain there (out of your sight) might mean a flash flood here. Flash floods cause more deaths in the United States than any other weather- related phenomenon, including tornadoes and hurricanes.

The eastern sky is clear and bright as you reach the highway. You are glad you passed up that other camp at the base of yesterday’s last hill; morning muscles need a warm-up on the bike before attempting anything really strenuous. You mount your bike by straddling it first, putting one foot into its toe clip, pushing off, then placing the other foot in its clip as you coast the first few yards. Fleeting pain registers from your butt as it settles into position, but the ache lessens as your whole body adapts to its familiar cycling pose. Spinning (pedaling rapidly) in your lower gears helps get your muscles warmed up and accustomed to their task for the day.

You are all alone on the highway during this very special, pre-sun period except for an occasional rabbit or tortoise that chooses to cross the road ahead of you. Suddenly you spot a coyote. He freezes in disbelief as he tries to interpret your intrusion into his world. You slow to a halt, then stand absolutely still until he tires of the game and lumbers off to see what unsuspecting prey he might find for an early breakfast. You use this opportunity to remove your warm-up jacket, placing it in the outside pocket of a rear pannier. Muscles are warmed up now and the coyote has given you the second smile of the day.

Back on the bike, your cadence is smooth as you approach the first hill of the morning. Gearing down, you grip the bars and put your legs to the test. The grade increases but you match it with your gears, suddenly finding your self at the top breathing hard but not overly tired. You are on a plateau with the sun just peeking over the horizon up ahead. Time to stop for sunscreen, lip cream and a drink of water and to attach your helmet visor since the sun will be hitting you directly in the eyes for an hour or so.

On the go again, traffic has in creased with daylight. You find yourself checking frequently in your rearview mirror and relying more on your ears to let you know what is happening behind you. There is about a foot of good pavement to the right side of the fog line; you know you might need it if crowded from the rear. When a big, semitrailer rig or bus approaches you drop to the down position on the handlebars and hang on to keep from being bumped around by the slipstream; that shoulder looks pretty good to you. If the road is narrower or another vehicle is approaching head-on so the vehicle to your rear can’t give you any room (otherwise most truckers and bus drivers will, most RV drivers won’t), it’s best to stop completely and straddle your bike until the danger passes.

Fast-moving, large vehicles kick up quite a slipstream, but it’s worse when the wind is blowing. If the wind is coming from your left or ahead, an approaching truck breaks its relatively steady pressure as well as tossing you around in its own turbulence. If the wind comes from the rear or your right, the shake-up won’t be as severe since the wind remains constant. A lot depends on the strength of the wind, the speed of the truck and the lay of the road. No matter what, if there doesn’t seem to be enough road for the two of you, stop to allow the vehicle to pass; it’s the polite thing to do. If there is room for the vehicle to go around, give yourself enough road space to maneuver in case of turbulence. Don’t ride on the very edge of the pavement; you are inviting the vehicle to edge by without passing properly. One slip of the wheel and you will be in the ditch on your head (helmeted, of course).

An hour has passed since you mounted up; it’s time to take a break. You look for a spot where notice both directions down the road, pulling off the highway completely if possible. The slipstream of a truck can knock over a bike parked on the shoulder whether it’s leaning on a post or a kick stand. You always try to park your bike standing up, either on its kickstand or leaning (carefully) against something solid. Laying a loaded, lightweight touring bike continually on its side subjects it to unnecessary strain and abuse.

A 10-minute break every hour helps you maintain a good touring pace. You resist the temptation to flop on the ground; walking around while you eat and drink helps keep your muscles loose and dries your shorts faster. Even if you don’t feel particularly thirsty, you drink something. As the day proceeds to warm up (you, too) you drink every 15 minutes or so to insure adequate hydration. Don’t trust thirst as an indicator of need.

On the road again, you see a cattle guard ahead. Frequently found in the West, they are pits covered with closely spaced steel pipes. Livestock won’t cross them so they serve as fences across the highways. It’s best to stop, dismount and walk across. Cattle guards are hard on your wheels and dangerous to your health if you slip while crossing. If you insist on riding over them, cross perpendicular to the pipes, not on a diagonal. The same goes for railroad tracks. Both of these are dangerous situations for cyclists; we speak from painful experience.

As the morning progresses with a cooling breeze from your own momentum in your face, you approach a small town — one where you are picking up mail sent in care of General Delivery. Your friends and relatives have been cautioned to put “Please Hold for Bicycle Tourist” on all mail so it won’t be returned (hopefully) as required after a two-week waiting period in case you are delayed. You are also expecting a tire from your local bike shop since the one you are riding on has a nasty cut and there are no shops on your route. In the post office, you pick up letters from home, new maps for the section ahead on your journey ( you left these pre-pack aged to be mailed by people back home on a set schedule), an unexpected box of homemade cookies, and some friendly words from the postmaster who has been wondering who you were and what you would be like. The tire arrived too, so you are all set for the next leg of your trip. This town was chosen as a mail drop because it was located on the route you were most likely to take, yet it was close to an alternative route you were thinking about. Before you leave the post office, you mail a postcard home notifying folks of the next mail drop if they don’t already know it.

The clock on the post office wall says it’s only 10:30 AM., so you decide to push on the next 18 miles to a larger town before it gets much hotter. You plan to change your tire during the afternoon break. A fruit stand just on the edge of town speeds you on your way with fresh fruit for now and a little in your pack for later. The proprietor lets you fill your water bottles there too and you still have the half-gallon in the folding jug for emergencies. There will be no water until the next town.

The 18 miles pass quickly except for one section that has been freshly tarred. It’s common for highway departments to put down fresh oil with a layer of sand and gravel for cars to pack down. Works fine for them but it’s murder on a bicycle. So you dismount and walk your bike on the dirt shoulder; better than riding through that messy, gooey stuff. A few cars honk as they pass; you recognize some people from the fruit stand as they wave. You are feeling good, physically alive, and one with blue sky and wide horizons. You can hardly tell where your own body leaves off and the scenery begins.

Toward the end of the 18 miles you begin to feel the heat, approaching 100°F, now, and you know it’s time to get off the road through the middle of the day. There is no longer a breeze as you match the speed of the wind to your rear so you feel like you are pedaling in a dry sauna. As your thoughts turn to shade trees and swimming pools, you spot the next town just ahead. Larger than the last, it’s still small enough to cruise around easily on your bike for a quick reconnaissance. Is there a shady park? A coin laundry? Maybe showers at a truck stop, at the laundry or at a public swimming pool? Sometimes independent motels will let you shower for a small fee during the quiet daytime hours. You take a good look around since you plan to be here three to four hours. A stop at the chamber of commerce building tells you there is both a coin laundry and a swimming pool, the latter in a big, shady park. The town planner comes out to shake hands and discuss bike touring in general, his town in particular. He likes your idea of developing a list of families who would be interested in putting up bicyclists overnight to keep on file at the chamber of commerce.

Laundry first, fun later. In the laundry rest room you change into your swim trunks or clean clothing if you have any at that point. (Susan uses our lightweight tablecloth as a sarong while everything else is in the wash.) Laundry times can be filled with letter writing, journalizing, map study or catching up on the newspaper. You might simply sit and watch your clothes going around without you.

Once the laundry is done, a rumble in your stomach sends you cycling to a grocery store to pick up lunch and a can of frozen orange juice concentrate to mix in your water bottles. With a pinch of salt it’s a cheap, comparable substitute for more expensive athletic drinks, which can be impossible to find in many small towns.

Now to the park to relax, eat, swim and shower. Be sure to take in every thing you will need if the pool is in the usual fenced enclosure. Lock your bike to the fence or some other permanent object within view. This pool lets you exit and reenter for a single fee so you take a quick, refreshing plunge, then re tire outside near your bike for a nap under a shade tree. You continually sip orange juice and water throughout the afternoon to maintain your liquid and electrolyte levels.

After your nap you decide to change your tire, clean up your bike and oil the chain. With a small, damp rag you start at the top and work your way down, all the while looking for any problems that might need your attention. Then you use your cutoff, one-inch paintbrush to clean off the cluster. With the newspaper you were reading earlier (or one appropriated from a trash can) you shield your bike as you spray and wipe down your chain. As you lock up the bike again after putting away your tools, there is time for another swim and a good, soap-down shower before step ping into your clean clothes.

By now it’s 4:00 P.M., the worst of the day’s heat is over. It’s still in the high 90s but you feel strong and refreshed from your long stop as you pack up to hit the road once more. The next town is 20 miles away, but you have checked with at least two people who say the market there is open until 9:00 P.M. You decide to wait until then to buy your food for dinner, breakfast and to morrow’s snacks.

Outside of town you begin to climb more rapidly on approaching the mountains. Passes are higher with shorter downhill jaunts in between. Small subsistence ranches fill valleys as the uninhabited desert gives way to marginal farmland. Gone are the red rock mesas and buttes of the desert, which filled your days with deep shadows and gaunt shapes testifying to an eon of wind and water working on unprotected land. You miss them in a way, as though friends have been left behind. But lonely ranches fill the void where farm families sometimes wave to you from front porches in this late afternoon.

About a third of the way up a particularly steep climb, a dog comes racing out from a ranch barking every inch of the way. Most dogs you encounter have limited territorial bounds, usually stop ping at the road. You automatically check for your small spray can of Halt dog repellent mounted on the handle bar stem — it’s the same as mailmen use — and find it reassuringly in place. Some of your cycling friends use their pumps as weapons against dogs, but you think that is too dangerous for both you and the animal. Instead, you always attempt to outrun them unless you get caught laboring up a grade like this one.

Oh, oh. He is a big one and still coming fast. You shout a firm, authoritative “No!” but Dummy doesn’t even check his pace. Concentrating on con trolling your bike and watching the road, you wait for him to cross the point of no return onto the highway, then taking aim, you let loose a stream of Halt as he gets about ten feet from your leg. Dummy acts like he hit a brick wall, tumbling head over heels and coming up pawing frantically at his nose. You are forgotten as he tries to get at the offending material. Halt is only red pepper and wears off quickly, therefore harmless to the dog, but there is no doubt about its effectiveness if your aim is good. You love dogs in general, but you know that you have not only saved your own skin, but that this might deter the dog from future encounters that could end his life under the tires of a non-forgiving truck. That wouldn’t wear off. You hope he has learned a lesson; one good thing, you certainly got to the top of that hill in record time.

At the top of one particularly grueling ascent, there lies before you a long, steep, winding downgrade of two miles or more into a major river valley. It’s a good time to take a break to allow the sweat of the last climb to evaporate be fore the long, cooling descent. While you drink and eat a snack, you walk around your bike checking to make sure there will be no surprises as you sail down at high speed. Brakes, tires, spokes, cables and gears are all in or der. You also check the rack and rear load to make sure it’s still tightly cinched and secure. Back on your bike, you wait for a long break in the traffic before pulling out onto the road.

You move into the drop position for maximum control with sure access to the brakes. As the landscape sails by at increasing speed, you apply the brakes in short blasts — the rear just a fraction before the front. Using both brakes, you apply a little more pressure to the front as that takes the brunt of the weight, but the back brake is equally important in acting as a drag to keep the rear down. Since it’s still pretty hot, especially the road surface, you stop halfway down to check for overheated rims. There isn’t much danger since you are riding with clincher tires instead of tubulars, but caution is needed since the rim could conceivably heat up enough to blow the tube. Braking friction can soften the glue on tubulars enough that they could roll off the wheel at the worst possible time. Either way, it’s best to stop part way through a long descent with a heavily loaded bike to check the rims. If they are too hot to touch, wait for them to cool somewhat as you enjoy the view, take some pictures or have a drink.

Back on the road you are careful to ride a little farther out than normal to avoid loose gravel or other hazards that might be difficult to negotiate at this speed. You feel comfortable in the nor mal path of the right wheel of automobiles, away from the dangerous oil slick between the wheel tracks. On hot days such as this one, or when the road is wet, this oil track becomes a real hazard — especially to a loaded bicycle traveling downhill at high speeds. Because you are aware of the hazards, are pre pared for anything, and know that you and your bicycle are in top condition, you thoroughly enjoy this long, downhill run with no mishaps.

Since you don’t yield to the temptation to let all systems go in a totally out-of-control, breakneck descent, you pedal most of the way downhill in your highest gear, keeping your leg muscles warmed up and preventing cramps from windchill on overheated perspiration- soaked legs. Sometimes pedaling is more of a spinning exercise but it serves the purpose.

What a great ride! At the bottom the road turns to follow the river gradually upstream into the mountains that begin to close in on all sides. You have truly left the desert now and are in the Rockies. Your eyes welcome the darkening, descending line of green timber, which seems almost to rush into the river valley as you climb steadily higher. During a rest stop you check your map and see that the town where you will be buying dinner is just up the road, possibly two or three miles away. You hope to camp at a forest service campground 11 miles beyond the town. If you don’t make it that far, there is plenty of open country in which to camp. But it’s only 6:00 P.M. and doesn’t get dark until a little after 9:00 p. you figure you will be setting up camp around 7:30 P.M. with plenty of daylight left.

As you roll into the sleepy little river town, you locate the market on Main Street. It’s no supermarket but will surely have what you need since you are not relying on hard-to-find, specialized lightweight foods. You lock your bike in front of the store near a window but out of everyone’s way. Just in time you remember to remove your helmet, sunglasses and rearview mirror, smiling as you recall the startled look on the storekeeper’s face at that tiny town in Utah last week when you forgot to do that. He must have thought you to be from the moon. Your handlebar bag comes off quickly to accompany you into the store since you will need your list, pen, traveler’s checks and ID for this “serious” shopping trip.

The store is busier than you expected with people gathered around the bulletin board reading about local happenings and others gathered around the cooler drinking Cokes. They are friendly and some who saw you ride up ask where you are going and where you come from. They are surprised that you have been on the road two weeks, averaging 70 miles a day. One old rancher tells you about the high mountains up ahead and offers to take you over the pass to spend the night on his ranch in the next valley. Tempted, you think about it, then decline his offer, trying to make him understand that you are doing just what you want to be doing by choice. That is what cycle touring is all about. He smiles, shakes his head, and says he is jealous of your freedom and wishes he were “young again.” You tell him about your 66-year- old touring partner in the Appalachians last year. He laughs and says maybe he’ll take up doing what you’re doing then, in his “old age.”

You fill your grocery cart with food for dinner, breakfast and snacks tomorrow. The thought of fresh lettuce, orange juice and cold yogurt prods your appetite as you pay for your purchases and load them all into your panniers with a loaf of bread riding temporarily on your back in the canvas guide bag you carry along just for such overloads. You filled your water bottles but know from your campground guide that there is water at your evening’s destination. You have emptied the folding water jug since you will be following a stream all the way and have water-purification tablets in case you don’t get to the camp ground tonight.

The road gets really steep as you begin to feel the day’s mileage in general weariness. You are thankful when you pass the national forest entry sign; your camp is not far now. The road narrows as it winds upward. You force yourself to concentrate on what is ahead and what notice in your rearview mirror. Drivers, especially if they are from out of state and not accustomed to driving in the mountains, tend to panic a little on narrow, winding roads. You, on your fully loaded bicycle, are not one of the sights they expect to see around the next curve.

Just then you spot a huge motor home rounding the curve behind you. Glancing ahead you see nothing but traffic; he won’t be able to pull around you and he doesn’t seem to be slowing up at all. There would be room for him to pass except for the mirror that sticks two feet out into your space. You know he must be unaware of the danger it represents for you as he is not attempting to slow his speed at all. Since what little shoulder there was disappeared about a mile back, you immediately pull off onto the dirt edge and wait for him to pass. The driver waves at you in a friendly fashion, seemingly unaware of your panic.

Your knees are a little shaky as you get back on the road and push pedals again. With more than the usual relief, you enter the turnoff to the camp ground, a small forest service sign at a dirt road going into the woods at the right. It’s an older campground with small spaces pleasantly tucked into the forest — a tenter’s paradise. There are only a few other campers spread throughout the 11 sites you have to choose from. Finding a fairly isolated spot away from the outhouse, you pedal back to the entrance and deposit your two dollars at the self-service permit station.

With an hour or so of daylight left, you pitch your tent, fluff your sleeping bag since it will be much cooler tonight than you are accustomed to, and pre pare dinner. As you sip the chicken bouillon you prepared in water boiled while setting up the tent, you fix a salad with fresh green lettuce and ripe tomatoes. When it’s ready you start the pasta cooking for macaroni and cheese, your main carbohydrate for the evening. Dessert is a big cup of yogurt as you lean against a ponderosa pine watching the sun’s last display of color in the west. Food never tasted as good.

ABOVE: Some cyclists prefer to travel alone because they feel it permits greater

independence and mobility.

A final batch of water warmed on your stove goes to do up your few dishes with enough left over for a sponge bath as you change into warmer clothing for the evening. Although it isn’t really cold, you have been so long in the desert that the mountain air at 6,000 feet seems to have a chill to it. There will be no difficulty sleeping to night.

As you finish up your chores, some of your camping neighbors walk by and stop to talk. They are curious about your mode of transportation and seem a little amazed at your lack of gear. When they ask how far you came today, you realize that you don’t know so you get out the map to check. It turns out to have been an 84-mile day, really good for the amount that was in the mountains. They laugh because they have come that far in their car since mid-afternoon. But this day will stand out in your life as special, filled with sights, sounds, smells and experiences that will make you forever feel a part of this piece of the world. For them, it was just another long day behind the wheel on the way to somewhere else.

The couple, somewhere in their mid-thirties, say that they would like to try what you are doing sometime but don’t think they could make it. You try to convey to them your belief that anyone who is physically capable can travel long distances by bicycle if he really wants to. It has been done by the deaf, the blind, and even by people with only one leg. The secret is in a heart and mind that are curious about the world, and flexibility enough to fit in just about anything that comes along. But their questions center on the kind of bike you have, what sort of camping equipment you use and how extensive has been your physical conditioning. All of those things are elements, but they are not what is important. You tell them instead that yes, you are organized and yes, you need to be aware of the difficulties, but most of all you need to be loose enough to accept unforeseen circumstances such as breakdowns, detours, and an outstanding sight-to-see as additions to your tour, not interruptions. Bicycle touring itself becomes the whole experience; everything else — including get ting where you are going — is just a small part of the larger whole.

You smile to yourself remembering your first tour. You had eight days, yet came home four days early after several mechanical breakdowns and missing a bus when it became apparent that you wouldn’t be able to complete the tour as you planned it. Now, you would simply change your plans accordingly and spend all eight days on the road, even if it wasn’t the “original” road. Any road will do; it’s the traveling on it that counts.

Your guests wander away, convinced that they really would like to take a bike tour if only. . . But perhaps meeting you has broadened their horizons to the point that one day they will match their wishes to wheels.

It’s completely dark now with stars as your rooftop companions. You take your panniers into the tent after locking and covering your bike. There will be dew in the morning, the desert seems a long-ago memory. You put your bike light, water bottle and wristwatch next to the head of your sleeping bag. You won’t need an alarm in the morning to beat the heat of the day. As you lie in bed you can hear all sorts of night noises as the world outside your tent passes into the care of the nocturnal. You hope their night is as fruitful and happy as your day has been.