Success in racing depends on a combination of four elements: physical fitness, bicycle-handling skills, strategy, and tactics.

In addition, there is the bicycle itself (see Part A). There is also psychological motivation, but that's beyond the scope of this guide. Bicycle-handling skills, strategy, and tactics are addressed here; fitness is addressed in Part C.

Riding in a tight group, or peloton, is an integral part of racing. The peloton sets the pace for a race and provides protection from the wind for most of its riders most of the time. Although there are times when you must break away from the peloton if you hope to win a race, it's essential that you learn to ride effectively within the group.

MAKING CONTACT

When riding in a peloton, you literally rub shoulders and bicycles with other riders, so it is important that you learn how to maintain control in these situations. The best way to learn is to practice with a partner and an old bicycle in a grassy field.

If you fall, the grass is a lot more forgiving than asphalt.

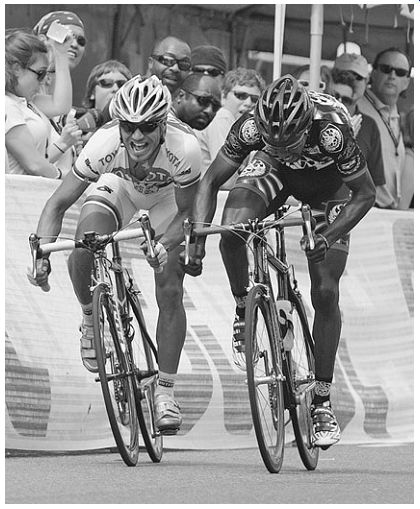

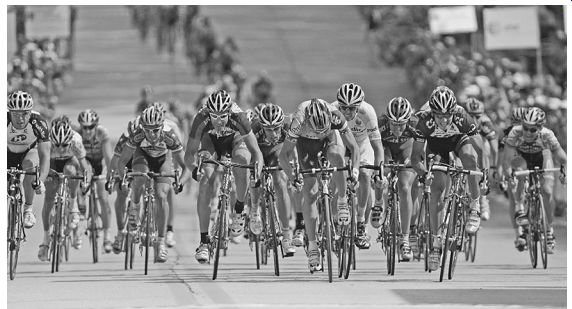

----------- Physical contact with other cyclists is inevitable when riding

in a group.

Start by gently touching shoulders as you ride.

Then work your way up to leaning into each other and pushing off. Keep both hands on the handle bars and use your shoulders, elbows, even your head to push off. Do not allow the bicycles to touch because you'll probably go down. And as tempting as it may be, do not try to knock your partner over; this is not a king-of-the-hill contest. Even on grass at slow speeds, you can become seriously injured.

When you're comfortable pushing off, work on touching tires, again using old bicycles on grass.

While riding slowly, approach from behind and gently touch the side of your front wheel to the opposite side of your partner's rear wheel. (Keep the point of contact behind your partner's rear axle.) When the wheels touch, instinct tells you to pull away immediately. Resist doing that; it often results in a crash. Hold your bicycle straight, maintain control, then gently pull away. Do not attempt this drill with a nice set of wheels.

When racing, you'll often need to move up through the peloton toward the front, where you can react to situations that occur there or create some of those situations yourself. Most of the time, riders will give way when they realize that you're intent on coming through. But they won't always do that, so you must learn to "push" your way through. This is another skill to practice in a grassy field.

You'll need at least two other riders to con duct this drill. While your friends ride next to each other at a slow pace, you come up from behind and work your wheel into the gap between them. Verbally let them know you're there, then push through.

You may make some contact with one or both of the riders. Stay calm and work on maintaining control using the skills just discussed. Keep in mind that you are not physically pushing your way through.

Because you've let the riders know verbally and physically that you're coming through, they will make way. This drill is designed to give you confidence when moving up through the pack. Concerning the "verbal" part of this procedure, be as loud as possible without being rude. You want to leave no doubt that you're coming through, but you do not want to start an argument.

All of these drills contain the potential for crashes and injury. Wear a helmet, keep things slow and controlled, and use common sense. Ride an old bicycle so you won't care if it becomes dam aged, or a mountain bicycle, which is more rugged and stable than a road bicycle.

-------------- Practice making contact in a controlled situation before

it happens on the road.

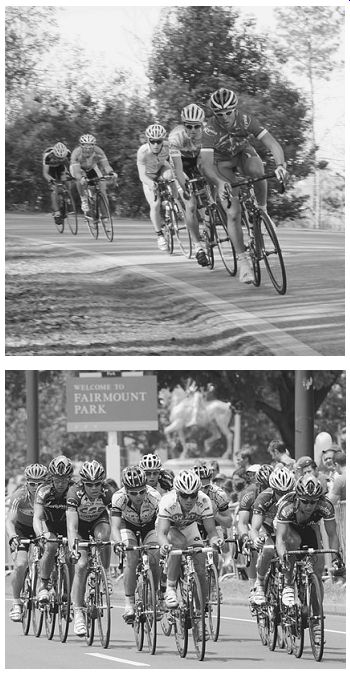

----------- Pace lines can be conducted in a single line (top) or a double

line (bottom).

PACE LINE

Conserving energy is among the most fundamental of race strategies, so cyclists form pace lines to save energy while maintaining a faster pace than they could do by themselves. Pace lines are single- or double-file columns of cyclists in which the rider at the front blocks the wind for those behind. There are a few conditions that determine whether it will be a double or single pace line. High speeds tend to lengthen the peloton into one long line. During group rides it is difficult to be social when riding in a single pace line, so most social rides are usually ridden in a double pace line. Safety also deter mines whether to ride in a single or a double pace line. On narrow roads or in areas of high traffic, cyclists should ride in a single line.

In a pace line the lead rider rotates frequently off the front and is replaced by the rider behind him. Thus everyone shares the hard work in small bits, and everyone benefits aerodynamically. There is an estimated work reduction of 30 to 40 percent when riding this way compared to Cycling alone.

To obtain the optimal effect, riders must keep their front wheel 4 to 12 inches from the rear tire in front of them. Any more than that and they will have to ride just as hard as the individual on the front of the line but receive no benefit.

It takes good bicycle-handling skills and a lot of practice to ride comfortably in a pace line. It is your responsibility to stay off the wheel of the rider in front of you. You must hold a steady, predict able line, guiding your bicycle smoothly and without extreme steering deviations. A cyclist who swerves back and forth is impossible to draft and creates a precarious situation. Practice while riding alone: hold a line by riding along the white line at the side of the road. Once you can do this without extreme concentration, you're ready to start working with a group.

Keep your hands near the brake levers, and pay attention to the riders in front of you as well as the road itself. (If your bicycle has aero bars, do not use them in a group or pace line. They place your hands away from the brake levers, thus slowing your stopping time. The one exception to this rule occurs in training for team time trials.) Don’t overlap the tire of the rider in front of you; that's just asking for a crash, which will likely cause a chain reaction involving everyone behind you.

When you, as the lead rider, are ready to drop off the front, pull to the side and drop to the back of the line by moving to the right or the left. Both sides have advantages and disadvantages. Drop ping back to the left (outside) gives you more room to maneuver but puts you in the path of traffic. Dropping back to the right (inside) keeps you out of traffic but provides only a narrow path to the back of the pack. It also puts the group a little farther into the road. You should not randomly decide to drop back to the inside or outside. In stead, the group should determine ahead of time which side the lead rider will use, then maintain that side throughout the ride, so everyone's movements are predictable.

Before pulling to the side off the front, you should look to ensure that your path is clear to the back. Pull off and slow slightly. When you are within two or three riders of the back, begin to pick up speed again, then slip onto the back. If you wait until the last person passes you before you accelerate, you'll have to do more work to get back on.

How long a rider stays on the front varies with the individual and the goal of the pace line. During races, riders spend only a short time on the front, allowing a faster pace to be maintained without wearing down any individual cyclist. During easy training rides where the pace is slower, cyclists spend longer pulling on the front.

Individual fitness and race tactics also influence the time spent on the front. If you're on a breakaway with individuals who are stronger than you are, you may need to spend less time on the front and more time recovering by sitting in (staying in the slip stream and off the front). You may even need to sit out a few turns every so often to recover, or stay off the front completely. To stay off the front, stay on the back; when the rider at the front pulls off, create a gap between yourself and the rider in front of you, allowing the rider coming back to enter the line in front of you. Although this will not win you friends, it will enable you to stay with the group when you might not be able to otherwise.

One of the most common mistakes that new riders make is staying too long on the front and slowing down the pace. If someone is yelling for you to get off the front, oblige him or her. If you are not slowing the pace, other cyclists will happily allow you to stay on the front as long as you want, wasting your energy while they conserve theirs. Don’t stay on the front until your legs are screaming, though. In either case, rotate back, recover, and await your next turn.

Do your best to maintain contact with the group. Avoid being dropped off the back of the peloton; if you are alone, it is extremely difficult to get back on. If you are not the only cyclist dropped, you may be able to work together to close the gap.

But if you are having difficulty keeping contact with a small breakaway, you may want to drop back to the main group and hope they catch the break before the line.

---------- In a double pace line, the cyclist in front will pull off and

drop to the back of the line on their respective side.

Rotating Pace Lines and Echelon

Riders in a rotating pace line and echelon (explained later) continually rotate in a circle to keep the group moving at a fast pace. No rider spends more than a few seconds in the front. It takes more coordination to ride in these formations than in a regular pace line.

A rotating pace line is used in a headwind, a tailwind, or when there is little or no wind. Two columns of cyclists ride side by side. The inside column moves up and the outside column moves back. The lead rider on the inside moves over to the front of the outside column at the same time that the last rider in the outside column drops back and moves to the end of the inside column, immediately resuming the pace of the rider in front. Riders continually rotate, spending little time on the front, in order to keep the pace of the entire group high. The inside lane is usually referred to as the fast lane, and the outside lane as the slow lane.

An echelon is used in strong crosswinds; the line slants in the direction of the wind to shield the greatest number of riders. A slanted echelon rotates across the lane instead of straight back, so it's important that it not cross the center line into oncoming traffic on an open course.

Think of a slanted echelon as having front and back rows. The front row circulates into the wind. The most exposed rider in the front row drops back to the second row and begins circulating away from the wind. The angle of the echelon tends to adjust itself automatically as riders feel themselves in the most sheltered position from the wind.

Slanted echelons have only about six to eight riders, depending on the width of the road. When more riders want to keep the same pace, more than one group forms, one behind the other.

A slanted echelon is much harder to maintain than a straight one and takes longer to learn.

When moving through rotation, you must pay close attention to the riders around you to ensure that you don’t cross wheels.

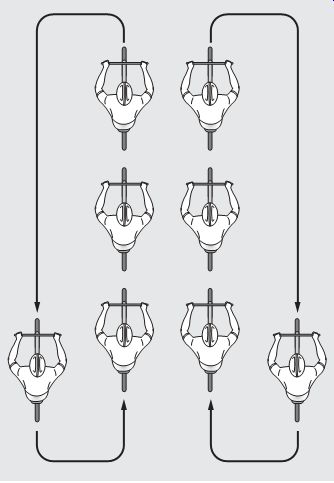

----------- An echelon is a rotating pace line used to combat crosswinds.

The echelon slants into the wind, with the rider in the front row rotating

toward the wind, then dropping into the back row, which rotates away from the

wind.

STRATEGY

On the surface, a Cycling race appears to be nothing more than many riders trying to beat one another to the finish line, and the fastest rider wins. In reality it is as complex as any chess game, and often it is the smartest rider, not the strongest, who wins. Strategy consists of an overall game plan for the race, and a choice of tactics at the appropriate times.

Pacing Athletes learn early to pace themselves. If you go too hard too soon, you will "blow up" and have to drastically reduce your workload just to complete the distance. If you go too slow and lose contact with the peloton, you forfeit the benefits of drafting and will probably never catch up. An optimal race pace is the highest one you can maintain without blowing up, right up to the finish line. Nevertheless, there are times when pacing goes out the window.

The best example of pacing in cycling is the time trial, where each cyclist rides against the clock.

If you ride too hard, you blow up before the finish; if you do not ride hard enough, you still lose. It's a fine balancing act.

Each cyclist's pacing strategies are based on previous experiences racing similar distances.

The more experience you have, the better you can pace yourself through a time trial. Most experienced riders start with a slightly elevated pace, quickly level off into a maintainable rhythm, and pick up the pace near the end, usually 1 to 2 km from the finish. Beginners often go too hard in the beginning. All cyclists tend to make small adjustments throughout a race based on how they feel and how many miles remain.

Pacing in a road race or a criterium is usually set by the riders on the front. Due to the benefit of drafting, the group is able to maintain much higher speeds than individual cyclists can on their own.

Staying with the main group during most of the race is necessary; however, there are times when you should set your own pace. During long climbs, if you can't handle the pace of the group without blowing up, drop off the back and try to get back on during the descent. Attacking also requires individual pacing. Once free from the group, you will need to hold your individual time-trial pace. In a small group that has broken away, pace is determined by the fitness of the riders in the break.

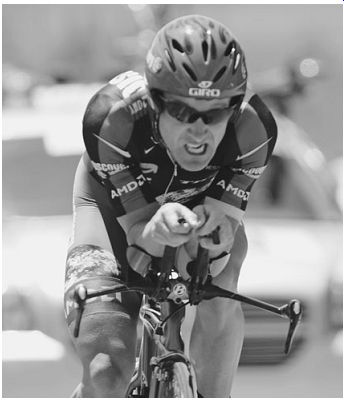

------------ Pacing is the key to riding a time trial. Cyclists must adopt

a pacing strategy that allows them to push as hard as possible without prematurely

fatiguing.

------------ Although cycling appears to be an individual sport, it's

very much a team sport.

Racing as a Team

Although cycling is very much a team sport, it is perhaps unique in that individuals and teams compete simultaneously, and individuals, not teams, are the victors. A cycling team works together so that one of its members will win the race.

Professional cycling teams hire riders with specific skills to fill specific positions. They hire climbers to climb, sprinters to sprint, and domestiques to work for the lead riders on the team. During flat stages, teams work to ensure that their sprinter is in position to sprint for the line at the end of the race. When racing through the mountains, the team works to protect their climber so they can exploit their strengths while climbing the mountain and win the race. The goal of a cycling team is to use the strengths of their team members to place their lead rider in an optimal position to cross the finish line first.

Racing clubs usually need to be more egalitarian, but it's sometimes hard to convince an individual to throw away his chance at victory in order to assist someone else's. A club must try to persuade its riders that they are all working for a common goal and should perform their assigned tasks to the best of their ability to secure a win for the team.

Racing as an Individual

For many cyclists-especially beginners-there are few opportunities to race on a team. Racing as an individual can be difficult, especially at races where teams dominate.

Individuals constantly form ad hoc agreements with other riders to cooperate on tactics--for example, cooperating on a breakaway or a chase.

These agreements may be explicit or implicit, sym biotic or one-sided, but they are fragile and transitory, and ultimately you are competing against these temporary partners.

As an individual rider, you can’t depend on anyone to blunt the wind for your benefit exclusively or assist you in pushing up through a group, so you must use smart tactics. Try to stay near the front, ready to respond to moves from other individuals and teams.

One advantage to racing as an individual is that you can conserve energy by staying off the front of a pace line because you do not have to blunt the wind for anyone.

TACTICS

The methods by which you implement strategy are called tactics. Doing the right thing at the right time involves understanding what's happening around you, knowing where you should be in the peloton at any given moment, knowing how to create desirable tactical situations, and deciding whether to instigate, join, or hinder an attack.

Several terms need to be understood before reading this section on tactics:

__Attack. A swift acceleration designed to separate a rider from the pack.

__Breakaway. An individual rider or a group of riders who have created a significant gap between themselves and the main peloton or smaller group of riders.

__Bridge. The act of closing the distance to a rider or group of riders when they have created a gap.

__Chase. When the peloton or small group of riders is working to close the distance to a rider or group of riders who are out ahead of the group.

__Counterattack. The act of attacking from within the chase group immediately after the group has caught the rider or riders whom they were chasing down.

__Lead out. The act of riding hard and fast at the front to provide shelter for a teammate and set him up for a sprint to the finish.

Stay Near the Front, Not on the Front

I have seen this situation occur innumerable times. A rider trains hard and well all year for the first race of the season. The race starts out a little slow, so this rider goes to the front and picks up the pace. He's feeling strong, and for miles no one escapes off the front, although several drop off the back. Finally, less than three kilometers from the finish, the attacks begin. The rider finds that he can't respond, his lead disappears, dozens of "weaker" cyclists blow by him, and he finishes near the back of the pack.

Although many tactics are employed in Cycling, beginning cyclists frequently ignore the most important one: don’t work harder than you have to. Stay in the group and enjoy the benefit of drafting. This is especially true for individual cyclists and weak teams. (Strong teams can afford to have cyclists on the front pushing the pace for their main riders.) By staying near the front, rather than on the front, you'll be in a position to respond to attacks or make a move of your own. (You'll also minimize the risk of being involved in a crash.) This does not mean you should never be on the front. If you are a strong cyclist and the pace is too slow, go to the front and attack aggressively, as discussed below. Once the pace has picked up, drop back and allow someone else to do the work, and get yourself ready for the last few kilometers.

------------- When initiating a break, attack hard so other cyclists are

not able to go with you.

Breaking Away

A breakaway occurs when one rider or a small group of riders attacks and breaks from the main group. This is designed to get the cyclists near the finish line with as few competitors as possible during the final sprint. A breakaway is therefore a good idea for strong riders, but not for strong sprinters who expect to come on strong at the end.

Initiating a break is always a gamble. If you never risk anything, you can never win, but breaking away isn't like bluffing at poker, so do not attempt it if you do not have the fitness level to pull it off. However, if you feel strong and the situation is right, attack like there's no tomorrow.

To initiate a successful break, you must surprise your competitors. Wait for a moment of inattentiveness and be careful not to advertise your intentions. Avoid attacking from the front. In stead attack from the side and behind the lead riders. The leaders won't see it coming, and those bunched elsewhere in the group will have trouble getting around the leaders to respond. Because everything happens so fast, you'll be off the front before anyone can respond.

A successful break always begins with swift acceleration. If you slowly ramp up to speed, you'll find a large group of grateful riders sitting in behind you.

If you intend to initiate a break, attack and attack hard, creating a gap between you and everyone else.

Once you have been off the front for about 400 meters, look back to make sure you're not giving the peloton a free ride. If you are, ease up and try again later. If you're alone, keep up the speed a little longer, then work into a time-trial pace. If you brought along a small group that broke away from the peloton, immediately begin working together in a pace line.

Certain times are particularly opportune to initiate a break:

__When there is a lull in the race, or the peloton is inattentive, is a good time to initiate a break.

__Immediately after a breakaway has been caught is an ideal time to counterattack. The riders from the first break will be tired, as will those driving the initial chase, and there will be confusion as to who will lead the next chase.

__If you can accelerate on hills, attacking near the top of the climb is a good idea. Don’t attack too early on the climb, or you will pay for it before the top.

__Winding roads with tight turns are another good place; it's easier for an individual or a small group to maneuver through turns than it is for a large peloton. Pulling out of the peloton's line of sight around a corner deprives chasers of a visual carrot.

Attempting a solo breakaway in a strong head- or crosswind is a bad idea, but a small group may excel under these circumstances. No one will want to get on the front and do the work necessary to bring the group back.

Joining a Breakaway

It's a gamble to join a breakaway because you do not know whether it will succeed. Familiarity with the other riders and teams in a race makes it easier to gauge a break's chances, but this comes only with experience. As a coach, I usually prefer aggressive mistakes to passive ones; I would rather see a cyclist go with a break that fails than have him sit in and miss the winning break. (Having said this, I would not want to see one of my cyclists make a break 10 miles into a 50-plus-mile race.) Do not be afraid to take a chance. You can learn as much from your mistakes as from your successes.

If you think a break will succeed, jump on quickly. If you did not initially make the break and it appears that the peloton will not respond, you must make a realistic judgment as to whether you can close, or bridge, the gap. If you decide to go for it, use the same methods as for initiating a breakaway.

If you join a breakaway, work with the other riders to ensure that the break will hold until the finish line. Even at the professional level, breaks sometimes fail at the finish because riders refuse to cooperate over the last kilometers: no one wants to work on the front, and the pace drops while the peloton picks up the pace and closes the gap. Save the tactics for the sprint to the finish. It's better to have a top-five finish than to be caught and spit out the back by the peloton right at the finish line.

On the other hand, try not to lead out your rivals in a sprint for the finish line by allowing them to sit in your slipstream until the end.

As you approach the finish line, there may come a time to drop the rest of the breakaway.

When you decide to go solo, attack from the rear.

After your turn on the front, drop to the back and fall a few bicycle lengths behind the last rider so you can build up speed and attack. Your momentum will carry you past the riders before they can respond.

If you are strong enough or lucky enough, they will not close the gap.

If you have a teammate in the break, attempt to wear down the rest of the riders with a series of attacks. Rider A attacks while Rider B, usually the stronger of the two, sits in on the chase.

The moment the group catches Rider A, Rider B comes over the top and attacks. If it works correctly, Rider B will be off the front. If not, Rider A sits in on the chase and waits to attack when Rider B is caught.

If your break is not close to the finish line and is being reeled in quickly, you have a decision to make. Can you and your group pick up the pace and maintain the gap? If not, do not blow yourself up.

Drop back to the main group, stay near the front, conserve energy, and wait for the next attack.

Help or Hinder? When riding as an individual, you should always help in the breakaway because you want to reach the finish line with as few people around you as possible. But if you know that the catch is imminent, shut it down and wait to be caught. Team riders may also choose to hinder the break if their main hope for a podium finish is back in the peloton.

There are two main strategies for slowing the break:

__sit in, and do no work that benefits the break

__actively slow the breakaway

Be subtle when attempting to slow a break away. Pull through when it is your turn, then slightly lower the pace and stay on the front a little longer than normal. Don’t drastically slow, or the others will just pull around and pick up speed.

Split the break by allowing a gap in the middle of the pace line. If you're lucky, the riders behind will not notice until the gap is significant. You will not make friends with this last tactic, and it will rarely succeed more than once during a break.

Chases

If a break goes off the front and gains ground, the peloton must decide whether to bring it back immediately or gradually, but it must be brought back. If it's early in the race, stay calm and work the break back slowly. If it's near the end or the group contains strong riders, bring the break back immediately.

--------------- When a breakaway occurs, the peloton needs to chase it

down.

How to Chase

The main group must work to bring a break back, but who will do it? Be patient; wait and see who will take up the chase. Many times, a team will come to the front and pick up the pace. If a team is willing to do the work, great. Sit in and conserve your energy. If a team has a rider in the break, however, the team may not be interested in bringing it back, especially if it's one of their strong riders.

If no one takes the initiative, you can attempt to lead out a chase. Go to the front and ramp up the speed. Stay on the front for a brief period, then pull off. Hopefully the group will maintain speed and you can sit in. Unless you're working for a team, do not stay on the front when chasing down the break. If you're able to put in that kind of effort, attack and attempt to bridge instead, making your own break from the peloton to join the leading group.

How to Stop or Slow a Chase

Individual riders should never stop or slow a chase: it is always in their interest that the break be run down. However, if you are part of a team and have a strong rider in the break, here are a few strategies you can use to hinder the chase:

__If no one has initiated a chase, move close to the front and just sit there.

__Once a chase has started, go to the front and slightly increase speed to give riders the impression that you're working on the chase, then gradually decrease speed to set a false pace. Eventually someone will catch on and pull through to set a real pace to bring the group back, but you'll have at least delayed the chase, which might be enough.

__Place riders strategically near the front, having them slow and create gaps between the lead chasers and the peloton. This will force riders to come around you and interfere with the chase.

------------- Climbs are ideal places for strong climbers to make a move.

Weaker climbers must make tactical decisions on how best to proceed.

Hills

If you are a good climber, hills are the ideal place to break away or keep the pace high and hurt the other riders. Watch for weaker climbers and try to stay in front of them. If they allow a gap to form between themselves and the riders in front of them, you may not be able to come around and close the gap; even if you can, you will expend extra energy doing so.

If you are a poor climber, you may want to move to the front before the climb begins. If you're lucky, the group will allow you to set the pace for a while. Immediately or eventually they will pass and you will begin to drift back through the group, but if things work in your favor you will still be close to the group when it crests the hill. If in stead you start the climb in the back, then the gap will only get larger. Don’t blow yourself up on the climb. Instead ride at a pace you can handle, and attempt to close the gap after the climb.

If the climb is long and hard and the main group is keeping a pace you can’t handle, drop from the group and ride your own pace. In most cases you won't be the only one off the back and you'll have other riders to work with.

Beware of pushing too high a gear up hills, or you'll tire quickly. Don’t allow your cadence to drop below 70 rpm unless you're standing. When climbing out of the saddle, cadence is determined by the gradient and personal preference. Through trial and error you will be able to determine what cadence works best for you when climbing out of the saddle. This is usually determined by the steepness of the climb.

Descending

Descending hills offers an excellent opportunity to gain time on your rivals. This requires a lot of confidence, which comes only through practice and trial and error.

Get in an aerodynamic position that still allows complete control. Keep your head up and look as far down the road as possible. When you are going so fast that pedaling is useless, get low on the bicycle and bring your elbows in. Position your cranks parallel to the ground and bring your thighs in against the top tube. If your bicycle begins to shake, stay calm and gently slow until the wobble subsides.

Most high-speed wobbles are caused by the rider being too tense. Trying to compensate instead of relaxing usually makes the wobble worse. Some wobbles, however, are caused by the bicycle. Check for a loose headset, spokes, or wheels.

------------ Being able to descend hills in a fast, controlled manner gives

you an advantage over many competitors.

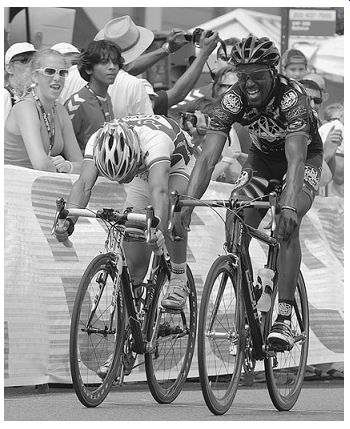

---------- Sprints are controlled chaos, with every cyclist contending

for the best line to the finish.

----------- "Throwing" your bicycle forward at the finish line

can mean the difference between first and second place.

Sprints

There's more to sprinting than just pedaling as hard as you can for the finish line. You must make decisive tactical decisions from the approach to the sprint all the way through the finish.

Your sprint strategy begins even before the race. Scout the approach to the finish line. If there are turns on the approach, determine your best route through them so you can position your self optimally in the peloton before reaching that point. Note potholes and other obstacles, and look for prominent landmarks that will help you gauge your distance from the finish line.

You can’t sprint timidly and expect to win.

You have to be right up near the front, and when you decide to go, do it decisively and own your path; it should be the straightest route possible from your current position. Avoid getting trapped between the group and the roadside barriers, which will seriously limit your options and create a potentially hazardous situation.

Don’t initiate your sprint until you're sure you can hold it to the finish line. Instead, sit on the riders that begin their sprint too early, and come around when you're ready to sprint for the line. Initiate the sprint in the same manner as a break. If there is a crosswind, attempt to at tack from the downwind side so your competitors are blocking the wind. Focus solely on your path and the finish line, give it your all, and ignore the other riders. As you approach the finish, focus your sprint about ten meters past the line to avoid slowing prematurely. Finally, "throw" your bicycle forward at the line by rapidly straightening your arms. The minute fraction of a second gained is often the difference between winning and second place.