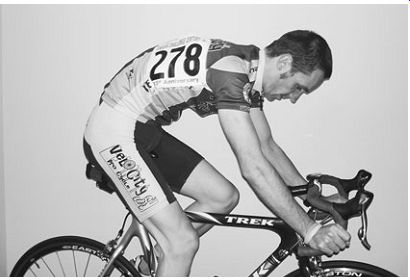

I suspect that the majority of cyclists who are reading this guide are into the sport for a little racing and for the health and fun of riding.

Even cyclists who are not interested in racing may be interested in watching competitive cycling. All cyclists can benefit from an understanding of the different categories of racing. And noncompetitive as well as competitive cyclists may be interested in participating in group rides.

RACING

When people think of bike racing, what usually comes to mind is a road race with a mass start, a set distance, and a finish line. This is not always the case, though; there are other types of races with variations of these characteristics. The USCF rule book gives detailed rules for all of the racing events discussed here. But for a general discussion, read on.

------------ Road racing is what typically comes to mind when you hear

a reference to competitive cycling.

Road Races

The archetypical race with which most people are at least vaguely familiar is the road race. It is held on a public road, with distances usually ranging from 25 to 130 miles and courses of one of four different designs. A point-to-point race involves starting in one place and finishing in another. An out-and-back race involves racing to a turnaround point, then returning by the same route. Many road races are single-loop races, where cyclists race in one large loop, starting and finishing in the same place. A circuit race involves a smaller loop that cyclists cover a number of times. Circuit races are the most spectator-friendly because the crowd sees each rider more than one time.

Another advantage of the circuit race from the organizer's point of view is that there is less road to close and patrol.

In many road races, different individuals race different distances based on their experience level as established by the USCF in the States, and other governing bodies elsewhere. (The USCF is the road racing division of USA cycling, the sanctioning body for all types of bike competition in the United States.) Beginners start in Category 5 and move up through the categories as they improve.

For example, in one given race event, Category 5 riders may race 30 miles, Category 4 riders 45 miles, Category 3 riders 65 miles, Category 2 riders 80 miles, and Category 1 riders 130 miles. Many times, two or more divisions are grouped together at the same distance.

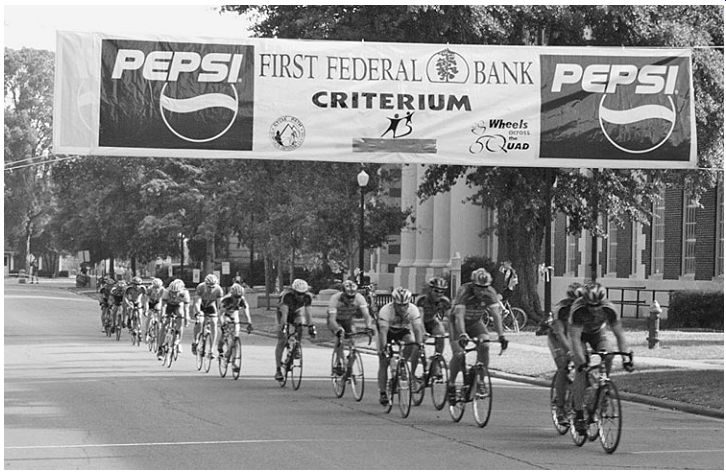

Criteriums

Criteriums (called crits) are short, fast races involving a looped course that cyclists race around numerous times. These courses are usually 1 to 2 miles long, with turns that can make the race difficult and technical, especially at the speeds that the cyclists hold throughout the race. The courses used in these races are usually flat but can be hilly. The length of the race may be determined by a number of laps or by a time limit.

To keep the pace fast, prizes are offered on specific laps. These prizes, called primes, are awarded to the first cyclist past the line on a specific lap.

Other methods to keep the pace fast are pulling out the last man on each lap, or pulling out lapped riders.

Due to the fast pace and tight turns, crashes are likely. This has resulted in another unique aspect of the crit: the free lap rule. If you crash or have a technical (a problem with equipment), you are awarded a free lap.

The combination of a short looped course, technical corners, fast pace, and primes makes these races exciting for spectators.

------------ Criteriums involve a short looped course, usually about one

mile, that riders race around multiple times. The duration of the race may

be a fixed number of laps or a set time limit.

---------- Time trials require that cyclists ride on their own against

the clock.

Time Trials

Time trials allow individuals or teams to race against the clock without the interference or help of other riders or teams. Individual time trials are unique in that the outcome depends entirely on each cyclist's ability. Time trials usually range from 5 to 35 miles and may be over flat or hilly terrain. Because of the lack of drafting (riding in another rider's slipstream, which is common in road races and crits), aerodynamics are extremely important in time trials. This has led to the development of special equipment and bicycles designed to improve aerodynamics.

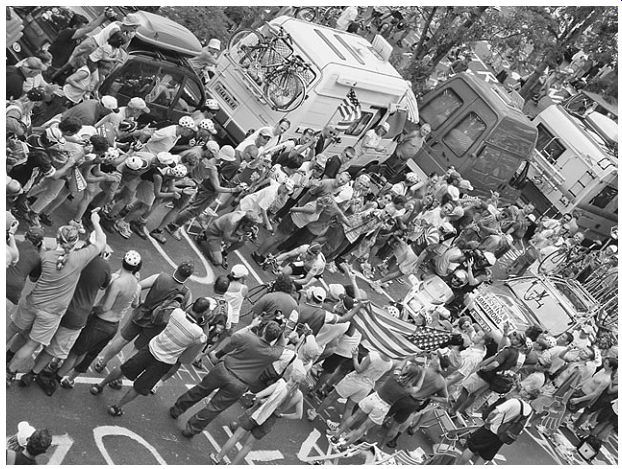

Stage Races

Stage races are a combination of two or more of the race types listed above; they range from two days to three weeks. (Most stage races in the United States last two days and consist of a road race, a time trial, and a crit.) Large stage races, known as grand tours, may include several iterations of each event. The most famous stage races are the Tour de France, Vuelta a España, Giro d'Italia, and, most recently, the Tour of Georgia and the Tour of California. The 2007 Tour de France consisted of three individual time trials and eighteen road races that varied from flat to mountain stages.

---------- The Tour de France is the world's best-known stage race.

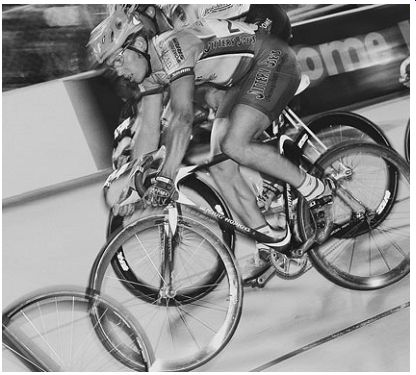

--------- Track races are conducted on a racetrack called a velodrome.

These races are short and fast.

Track Racing

This guide does not address track racing in detail, although it is briefly described to complete the picture of performance cycling (leaving aside off-road events as 100 percent valid but nonetheless a different sport altogether).

Track racing consists of racing short distances on a round track called a velodrome. Most tracks are 333 meters long but can range from 200 to 500 meters and are banked for cornering.

Races vary in distance and type. The most common distances are 200 and 500 meters and 1, 3, and 4 kilometers. Some of the most common forms of track racing are individual and team pursuit, time trial, elimination, and keirin, in which the racers are paced by motorcycles.

Cyclists use special track bicycles with a single speed fixed gear and no brakes. It takes a little while to get used to riding a fixed-gear bicycle because you don’t stop pedaling to slow down; you slow down by slowing your cadence. Fixed-gear bicycles are relatively inexpensive but may not be cost effective if you don’t live near a velodrome.

Most velodromes offer track racing lessons, and some even require them before allowing you to race.

Many velodromes also rent bicycles so you can experience track racing before investing in a specialized track bicycle. There are about fifteen velodromes in the United States; they are listed on the website of the American Track Association (see Appendix).

NON-COMPETITIVE RIDING

Many cyclists who have no interest in racing are nonetheless serious, committed riders. They enjoy noncompetitive events, which test their abilities outside a race situation and provide opportunities to ride and interact socially with other cyclists.

Supported and Charitable Rides

Supported rides provide resources and assistance to cyclists throughout the ride. A well-supported ride has aid stations at regular intervals along the route that provide food, drinks, bathroom facilities, and shaded areas to rest. One pays an entry fee to participate. Organizers run SAG wagons (defined variously as support- or service-and-gear), vehicles equipped and staffed to provide mechanical assistance and medical and safety support and to pick up cyclists who can’t continue for any reason.

Some well-organized rides are run on closed or semi-closed routes. The fewer cars allowed on the route, the more pleasant the ride and the smaller the chance of an accident. Route maps are often provided, and turns along the route are well marked with paint or signs. In some cases, volunteers supervise the turns, to keep riders from get ting lost and to assist in traffic control, especially at busy intersections.

Supported rides are frequently sponsored by charitable organizations, some of which do a fine job of raising funds through well-organized events. See the Appendix for three of the biggest supported rides (and their websites) that benefit charitable organizations; there are dozens, if not hundreds, more. Visit your favorite charity's web site to see whether it has a supported ride in your area. If it doesn't, consider organizing one and get in touch with the charitable-giving coordinator.

Non-supported Rides

"Non-supported" means just that-the group must be self-sufficient. The course is completely open, and there is no SAG wagon and no aid stations along the way. Participants meet at a designated time and place to ride as a group. The majority of local group rides fall into this category. Your lo cal bicycle shop should be able to tell you when and where local group rides occur.

If you are responsible for organizing a group ride, keep these factors in mind:

__Plan water stops, especially during periods of extreme heat. Churches, schools, and some businesses may provide good places to stop.

__Consider traffic patterns, and plan the safest route possible.

__Designate a sweeper to avoid leaving anyone behind.

__Require everyone to wear a helmet on all organized group rides.

__Develop route maps of the most common local rides.

If you are organizing structured group rides, you may want to have the participants sign an informed-consent release before their first ride.

The more structured the ride, the greater chance that you could be held liable for injuries.

FINDING EVENTS

Once you start looking for races or rides in which to participate, you'll be surprised at the number and variety within a reasonable distance from your home.

The USCF lists all sanctioned events on their website (see Appendix). Use the "Road" drop-down menu and select "Find a Race," then click on the state of interest to obtain race locations, dates, and contacts for more information. Many listings include links to websites for specific races.

Probably the most comprehensive site for racing and noncompetitive Cycling events is active.com, where you can register online (for a few extra dollars) for most events.

Small, local events may not be listed online, so visit local bicycle shops, most of which have an area for event announcements. The shop staff can often pro vide insights about local events, such as how popular, competitive, or well organized they are. Race and event information also appears in some enthusiast magazines such as VeloNews and Bicycling.

After you've collected the information, select the events you wish to participate in. Identify the key events that relate to your competition or fitness goals-where you want to be when you're at the top of your form (see Section 9 for details).

REGISTRATION

Many event organizers require registration prior to the day of the event. There are often two cutoff dates: an early one before which you can register for a reduced fee, and a second one that represents the actual deadline. Registration fees are not re fundable, so do not register for all your planned events at the beginning of the season. If you be come injured and can’t compete, you'll forfeit a large amount of money. Instead, mark the cutoff dates on your calendar and register for one at a time, preferably before the fees increase.

There are a couple of exceptions to this recommendation. Some events cap the number of entrants; if you wait too long, you won't get a spot.

To avoid being locked out, contact the race director to determine how fast the event fills up. Also, registering early may motivate you to train harder because you've already paid for the event and you know there won't be a refund.

MONEY

Racing can be expensive: entry fees, travel, hotel, food, miscellaneous expenses, and the cost of an annual racing license. When you budget for the up coming season, include the cost of transporting your bicycle. Most airlines charge about eighty dollars.

Any weekend event away from your hometown will easily cost several hundred dollars. Before you get in over your head, calculate the total cost of your season. Keep in mind that this does not include up keep and maintenance on your bicycle and gear.

Funding

Once you see the breathtaking total, you'll have to figure out how to come up with the cash. Consider establishing an "events fund" and putting aside a set amount each payday.

Many bicycle clubs hold fund-raisers to support their race teams, and commercial sponsorships are not out of the question. Many companies are interested in supporting athletics in their local communities and have money budgeted specifically for this purpose.

To make an effective pitch for some of that money, you'll need a good presentation. It should include the following:

__Team profile, including riders, director, coach, and other staff members.

__Team's past achievements and long- and short-term goals.

__What the company will gain from its sponsorship. Estimate the number of "eyeballs" that will view the sponsor's name through the exposure that your team or club will provide. You can offer advertisements on the team's jerseys, T-shirts, banners, and website. Signage on the team vehicle can range from large sign magnets to full-coverage graphics. Include images or examples of what you're offering.

__Altruistic benefits of the company's sponsorship: for example, raising funds for charity, or to promote fitness or athletic competitions.

__Outline of detailed operating expenses for one year of training and racing, to justify the need for sponsorship.

LOGISTICS

Do your planning well in advance to avoid stress over logistics as the event nears. Know where your accommodations are and how to get there. The race director can give you information about nearby hotels and campgrounds. Hotels near major races fill up quickly, so make your reservations early.

Whether you spend the night in the area be fore the race or drive to the area early in the morning, give yourself plenty of time and know exactly how to get there. The start of a race is stressful enough without having to worry about being on time, finding parking, checking in, and so forth.

Assume that everything will take longer than planned and include a margin of error.

If possible, travel a day or two in advance and stay the night, especially for an important race.

This will allow you to sleep later on race day and give you time to familiarize yourself with the course. Taking a "pre-ride" allows you to deter mine which sections of the course are easy or difficult so you can plan your race strategically.

The importance of a pre-ride is made clear by the experience of a friend who was unable to pre ride the course and was unfamiliar with the territory. He did know that there was a long, hard climb near the end of the race, so, as a strong climber, he decided to sit in (staying in the slipstream and off the front) through most of the race, then attack on the climb. Following this strategy during the race, he waited until he saw the crest of the hill in the distance, then he turned on the juice. No one came with him, and the gap just grew and grew.

Although he was beginning to fade as he reached the top, he still thought that his success was assured. When the road flattened out, he breathed a sigh of relief. Then the road curved to the right.

As he came around the bend, his jaw dropped as he looked at the remainder of the climb. He estimated that he still had a mile to go before the true summit. The peloton caught him on the last section of the climb and dropped him out the back. His misjudgment on the length of the climb cost him the race.

Find out from the race director whether there is neutral support-mechanical support provided to all riders in the race. At some races neutral sup port provides wheels for flat changes, but most of the time you have to supply your own wheels, which are carried in the neutral support vehicle.

Many smaller races don’t have neutral support.

At most criterium there is a pit area where you can place your spare wheels. You also need to determine the location of feed zones (specified zones where water and food can be passed off to riders), so you can plan accordingly.

---------- At larger races, neutral support provides wheel changes for

all teams.

--------- It's advisable to lay out your equipment and check it off a list

before packing it for a Cycling event.

EQUIPMENT CHECK

Can you imagine showing up at a race without some critical piece of equipment? It happens all the time. One of my cyclists arrived at a mountain- bicycle race without his front wheel, and a friend rode the bike portion of a triathlon wearing running shoes because he had forgotten his bicycle shoes.

We all run through a mental checklist before we leave for a race, but that's how we forget things. It's essential to have a physical list, such as the one below, on which you check things off in pen as you collect and pack your gear. (Photocopy this list for reuse, or write your own with your personal preferences.) Lay out your gear, and check off each item as you pack it. Do this the night before you leave.

Equipment Checklist

__bicycle (tuned and in working order)

__race wheels

__spare wheels for support

__helmet

__shoes

__jersey

__shorts

__socks

__gloves

__tire pump

__toolbox, spares, and supplies

__water bottles

__nutrition

__stationary bicycle trainer (for warm-up)

__proper rear cassette (you may need more than one depending on terrain)

__sunglasses

__sunblock

__medications (if needed)

Make sure your bicycle is in working order be fore you leave for the race. Check all bolts with a torque wrench. Check that your wheels are true and the spokes are properly tensioned. Check that the derailleurs shift properly and the brakes work well. Examine your tires; remove any foreign objects embedded in the tread.

Pre-Race Maintenance Checklist

__all bolts, but especially on the seat post, stem, and crankset

__pedals

__brakes

__shifters and derailleurs

__cleats on shoes

__wheel sets (trueness, spoke tightness, tires; check quick-release tightness on race day)

__headset

__frame and handlebars (check for cracks)

__chain (check for wear and lubricant)

It is also a good idea to outfit a dedicated toolbox to carry to races; it should contain all the bicycle tools and spare parts you may require. Many events have mechanics to help those in need be fore the race starts, but it is unwise to count on the availability of that support.

------------ Side placement for a race number.

---------- Back placement for a race number.

RACE DAY

You will need to awaken early on the morning of the big event. Bring a battery-powered alarm clock for insurance against a faulty hotel clock or a forgotten wakeup call. Get up early enough so you can eat breakfast two hours prior to the start of the race. Arrive at the race grounds early so you have time to park, check in, confirm start time, get organized, and warm up.

Sign in and pick up your race packet and race number at the registration/check-in table.

Ask the race officials how your number should be pinned: along your side or across your back.

Attach numbers so they catch as little wind as possible. Check for your start time. If you are racing a time trial, you need to determine your own exact start time. A race may start at 7 A.M., but your individual start may not be until 8:30 A.M.

This knowledge will allow you to better plan your warm-up so you can come out of the start gate primed to go.

----------- A stationary trainer allows a cyclist to warm up while remaining

close to the start and avoiding road traffic.

It is inevitable that there will be too many riders and too few portable restrooms (with hyped nerves, there's always an increased demand for the facilities). This leads to long lines, so do not wait until right before the start. Use the facilities before your warm-up.

Spend 20 to 40 minutes warming up before the start of your event. Time it so you arrive at the start line at the same time as most other riders-usually 5 to 10 minutes prior to the start of the race. Warming up on a trainer allows you to remain close to the start line and away from the chaos on the roads. Besides, it may be difficult or impossible to warm up by riding on the road prior to a race. If feasible, use a non-race rear wheel on the trainer, and switch to your race wheel after warming up. This will prevent you from prematurely wearing the tread on your race wheel.