The most economical way to upgrade your gearing is to change freewheel sprockets. Freewheel changes are inexpensive, since sprockets cost only $6 to $20 each. If your freewheel is an old model and sprockets are hard to find, you can replace it with a new one for around $40. If you have a racing rear derailleur and you want a significantly tower Low, you can buy a new touring derailleur and a new wide-range freewheel for less than $70.

It’s easy to change freewheel sprockets. Professional racers change sprockets before every race, to match their gearing to the race course. If you’re a serious racer or triathlete, you can do the same. Some freewheels make the task easier than others.

________ Status of the Freewheel Market ________

While there are a dozen crankset makers and a hundred or so different cranksets, freewheels are more straightforward. There are only four major makers—Maillard, Regina, Shimano, and SunTour—and they make only two or three models each, at least for the aftermarket. The Japanese companies, Shimano and SunTour, have done more basic research into freewheel design in the past decade than had been previously done since the freewheel was in vented at the turn of the century. At first, they concentrated on tooth shape and we saw innovations like alternate teeth and zigzag teeth and different tooth profiles for the different sprocket positions.

Starting about five years ago, some really significant improvements in freewheel design have occurred. In 1979, Shimano introduced the Freehub and Maillard introduced the Helicomatic. Both combine the freewheel with the rear hub, resulting in greater strength and easier sprocket changes. SunTour’s Winner Pro and Regina’s CX and CX-S allow you to build wide- or narrow-spaced, 5-, 6-, or 7-speed freewheels with the same body. In the last two years, freewheel research has concentrated on the interaction between chains, sprockets, and rear derailleurs.

Leaving out all of the new developments, the most important thing the Japanese did was to upgrade freewheel quality. Twenty years ago, low-priced freewheels were unreliable. Stories abounded of freewheels locking up solid, or freewheeling in both directions, 20 miles from the nearest bike shop. The companies that made those rotten old freewheels have either improved their product or gone out of business. Today, you can’t buy a bad freewheel. Any of the listed freewheels will take all of the punishment that you can dish out.

_______ Freewheels for Indexed Shifting _______

Indexed shifting has created a major change in the freewheel market. Today’s freewheel is part of a total system—like Shimano’s SIS, SunTour’s AccuShift, or Huret’s ARIS. Each of these companies makes their own free-wheels. (Sachs-Huret now owns Maillard.) These manufacturers have designed and calibrated their indexing systems around specific freewheel-chain-rear derailleur combinations. You can’t mix and match gear train components any more, as gear freaks have done since the time of the Wright Brothers. II you use “foreign” components, the onus is on you if the indexing doesn’t index. The freewheel is a critical part of the indexing system. The freewheel market has thus been divided into “have” freewheels that are suitable for indexed shifting and “have-not” freewheels that aren’t suitable. The indexed shifting freewheels have the following features:

Two basic configurations: narrow-spaced 7-speed freewheels for racing, and wide-spaced 6-speed freewheels for touring. Both are mounted on a 126mm wide rear hub. The old standard wide-spaced 5-speed free- wheel on a 120mm rear hub is now used only on the lowest-priced bicycles.

• Even spacing between sprockets. SunTour’s narrow-spaced 7-speed freewheels are unevenly spaced but SunTour’s indexed lever is de signed to match.

• Wide spacing on touring freewheels. The narrow-spaced 6-speed touring freewheel is history. You’ll still be able to get sprockets and spacers but the makers have removed the freewheels from the catalogs.

• Sprocket tooth profiles designed for easy shifting. Maillard, Shimano, and SunTour have special tooth profiles. Regina has introduced chisel shaped teeth on their larger sprockets.

• Fewer sprocket sizes. Indexed rear derailleurs can’t shift over very small or very large sprockets. Shimano doesn’t make an 11-tooth narrow-spaced sprocket for 7-speed Dura-Ace Freehubs. None of the indexed rear derailleurs are advertised for 34-tooth sprockets, let alone SunTour’s 38-tooth sprocket.

If you’re thinking about a new freewheel, think about indexed shifting at the same time. You may decide to buy the freewheel that goes with your future indexed shifting package.

______ Standardization ______

PHOTO 1 SunTour Winner Pro freewheels: top to bottom, narrow-spaced 7-speed,

wide-spaced 6-speed, wide-spaced 5-speed, and narrow-spaced 6-speed.

There’s no freewheel standardization, but that doesn’t matter very much. The only thing to worry about is the four different threads that screw onto the hub: ISO, English, Italian, and French. You want English or ISO threads, 1.375 inches in diameter by 24 tpi. The Italian thread is close to the English standard and you can mate English and Italian in a pinch. (Of course you can, that’s my ethnic background.) The new ISO standard thread is a compromise between English and Italian. If you have a French-threaded hub, sell it cheap, complete with freewheel, to someone you don’t like very much.

Everything else about freewheels is unique. It’s as if there’s a Freewheel Designers Politburo that requires a unique new remover and unique new threaded and splined sprockets on every new freewheel, so you can’t use your old ones. There are so many varieties that every now and then they blunder and a Shimano sprocket fits on a Regina freewheel. (I’m sorry Commissar, I’ll never do it again.)

________ Important Freewheel Features ________

The many freewheel models available on the market today can be distinguished one from the other by comparing several basic features. Below is a discussion of these features ‘in the order of their importance.

_______ Ease of Rear Shifting ______

Two freewheel factors enter into shifting: the shape of the sprocket tooth and narrow versus wide sprocket spacing. The freewheel interacts with the chain and the rear derailleur so it’s not quite that straightforward.

_______ Narrow versus Wide Spacing ________

A narrow-spaced freewheel requires a narrow chain. (I’ll talk about narrow spacing here rather than in the chain section because the freewheel is more important than the chain.) Narrow spacing is basically a simple idea. By reducing the width of the spacers between the freewheel sprockets, it’s possible to install six narrow-spaced sprockets in the same width as five wide-spaced sprockets, or seven narrow-spaced sprockets in the same width as six wide-spaced sprockets.

Width is critical because wide freewheels require an asymmetrical “dished” wheel. A dished wheel has the hub offset to make room for the freewheel. The way this is done is described in section 11. The width of the rear dropout and the width of the rear hub have to be the same. The two common widths are 120mm and 126mm. Today, most quality bicycles use the 126mm width. You can comfortably use a wide-spaced 5-speed freewheel or a narrow- spaced 6-speed freewheel with a 120mm width. You can use a wide-spaced 6- speed freewheel or a narrow-spaced 7-speed freewheel with a 126mm width. If you go beyond this, you’ll end up with excessive dishing and a weak rear wheel. Thus the number of sprockets and the sprocket spacing that you can use is intimately tied to the rear dropout width of your bicycle.

I’ve never liked narrow-spaced freewheels and narrow chains, because they don’t shift very well. It’s taken me ten years to be able to properly explain my objections. At first I blamed the narrow chains, and I kept testing one narrow chain after another seeking the holy grail, a narrow chain that shifted as well as a wide chain. I didn’t succeed because the problem isn’t the chain, it’s the narrow spacing between the freewheel sprockets.

When you shift to a larger sprocket, the derailleur jockey pulley pushes the chain over against the larger sprocket until the teeth engage the side of the chain and it climbs up. With wide spacing, the chain can bend 3 to 6 degrees before it runs into the next sprocket. With narrow spacing, there’s so little clearance between the chain and the sprocket that the chain can only bend about one-third of a degree. Then it contacts the side of the larger sprocket. Because the chain is essentially parallel to the sprocket, the teeth can’t find anything to embrace, especially since the rivets on narrow chains are nearly flush. So you pull harder on the shift lever and the flat side of the sprocket pushes back harder against the chain. Finally, with much grinding and mechanical sadism, the upshift takes place. It’s a complex mechanism since it depends simultaneously on the design of the rear derailleur, the shape and flexibility of the chain, and the shape of the sprocket teeth.

Smooth upshifting especially depends on the tooth difference between adjacent sprockets. Narrow spacing works quite well on a racing freewheel, known as a “corncob” or “straight block,” because of the single-tooth differences that exist between adjacent sprockets. A touring freewheel has much larger tooth differences and the flat sides of the big sprockets act like spoke protectors. If narrow chains and narrow spacing had started out as a racing innovation, we might have sorted out the problems when tourists started to fool with wide-range, narrow-spaced 18-speeds. Instead, it started out as a Fuji SunTour-HKK marketing gimmick for sport touring bikes: 12 speeds for the price of 10.

Then the racers realized that narrow spacing provided one more gear and one more one-tooth step, for the same wheel dish. The racers switched over to narrow-spaced seven-sprocket freewheels while we technical experts argued about the merits of the various narrow chains. We wrote about HKK’s Z-chain versus Sedis’s Sedisport versus Daido’s DID Lanner versus Shimano’s Narrow Uniglide until we finally sorted out what was really happening with the rear shifts. Narrow chains also shift a bit worse up front because they don’t settle onto the next chainwheel as readily as wide chains.

Shimano never played the narrow-spaced game. Instead they designed their Freehubs with wide spacing and minimum wheel dish. In 1987, Shimano finally introduced a narrow-spaced 7-speed indexed shifting racing package.

After flirting with narrow spacing, most of the mountain bike makers have switched back to wide-spaced 15-speeds, or they’ve widened the rear dropouts to 130mm to provide less wheel dish with wide-spaced 6-speed freewheels. Some sport touring bike makers still make poor-shifting bicycles with narrow- spaced 6-speed freewheels. That’s a sign of an old model (or an ossified designer). By 1987, the industry had pretty much standardized on wide-spaced 6-speed freewheels for touring bikes and narrow-spaced 7-speed freewheels for racers.

The final critical aspect of sprocket spacing is uniformity. If a freewheel is going to be used for indexed shifting, the sprockets have to be uniformly spaced. The new Regina Synchro and the SunTour Alpha freewheels correct the uneven spacing in the previous models.

Sprocket Tooth Shape

When I say “tooth shape,” I’m talking about the cross section of the tooth. In this area, Shimano and SunTour are miles ahead of Regina. The Maillard (Huret) ARIS is too new for me to evaluate. The European makers concentrated on racing freewheels and they didn’t seem to like or understand wide-range touring freewheels. As long as you don’t use a sprocket larger than 28 teeth, tooth shape isn’t too critical. When you use 32-, 34-, or 38-tooth sprockets, you need a proper tooth shape to help the rear derailleur shift.

Shimano does this by twisting the teeth so that the tooth corners snag the chain when you shift up. It works just beautifully. It works so well, in fact, that I don’t use Shimano twist-tooth freewheels in my rear derailleur tests because their eager shifting masks the small differences between derailleurs.

Shimano has done a lot of experimenting over the last decade. First, they left out every other tooth on their largest sprockets (“alternate teeth”). Then, they cut off the tops of one tooth on the large sprockets (“cross cut teeth”). Neither of these innovations seemed to make any difference. Then, they chamfered the teeth on the inside only (“chamfered sprocket”), which helped. Then, they twisted the teeth (“twist-tooth”), which really helped. Finally, they carved away the back of their twist-tooth sprockets (“super shift”), which shifted so quickly that you sometimes got two shifts instead of one. By the time Shimano introduced the SIS package, they knew what was needed for predictable shifts that matched the calibration of the SIS shift lever. Twist-tooth is their standard.

SunTour has played a similar game and their tooth profiles have changed over the years. They now have three different tooth profiles: symmetrical teeth for the smallest sprockets, asymmetrical teeth that are flat on the outside for the middle positions, and asymmetrical teeth with a set for the largest sprockets (“zig-zag teeth”). You have to be very careful assembling a SunTour free wheel. If you install the sprockets backwards, or if you install an outer sprocket in a middle position, the shifting is dreadful. — Until 1987, Maillard and Regina used symmetrical teeth chamfered on both sides with a flat top and a little groove. You can flop them over and get twice the wear but that’s their only advantage. Shifting deteriorates with more than a two- tooth difference between adjacent sprockets. This is particularly noticeable with narrow spacing. As a further insult, the flat top of the teeth sometimes allows the chain to ride on top of the sprocket until you kick it over with the rear derailleur. This doesn’t happen with Japanese freewheels. In 1987, both companies introduced new freewheels with a chisel-shaped tooth profile on the larger sprockets. Regina calls this Synchro. In 1988, Maillard (Huret) introduced a new ARIS tooth profile. On all makes of freewheels, the smallest sprocket (the one on the outside) usually has a different, more symmetrical profile, because you don’t shift up onto the smallest sprocket.

Neither Maillard nor Regina actively market a 34-tooth sprocket, which tells you something about their view of the touring freewheel market. ( FIG. 1 shows the various tooth profiles and TABLE 1 indicates the profile found on each freewheel model described.)

There’s a third reason that freewheels may shift poorly. The sprockets may be worn. Small sprockets wear out much faster than the larger ones. If you can see that the shape of the leading edge of the teeth on a sprocket is significantly different from the trailing edge, it’s time to replace that sprocket. Many people change the small sprockets whenever they buy a new chain.

______ Number of Speeds _______

The proper combination of chainwheels and freewheel sprockets was covered in the discussion on gear selection found in section 3. Before you pick out a favorite arrangement, measure the dropout width of your bicycle. If you’re building a loaded touring gear train, stick with wide-spaced freewheels, five sprockets with a 120mm dropout and six sprockets with a 126mm dropout. A narrow-spaced, wide-range 18- or 21-speed triple is a dumb idea. If you’re building a racing gear train, use a narrow-spaced freewheel, six sprockets on a 120mm dropout and seven sprockets on a 126mm. If you’re building an intermediate gear train for a sport tourer, establish your priorities. Do you want smooth shifting or two extra gears? It depends a bit on your gear patterns. Crossover patterns, which waste gears, need the extra two gears.

For a minimum cost upgrade, don’t change the number of speeds. Just buy new sprockets for your present freewheel. Sometimes you can convert a 5- speed freewheel to a 6-speed. SunTour Winners and Regina CXs are designed with this in mind. You can replace the outer sprocket with a two-sprocket pair on some Regina and Maillard freewheels. The easy way to revise a freewheel is with the help of your nearest pro bike shop. Freewheel sprocket boards are a hallmark of a pro bike shop. Before you spend a lot of money on a worn-out freewheel, check the cost of a new one. It’s easy to spend more on sprockets than on a whole new freewheel.

___ Smallest Small Sprocket ____

There used to be a standard for the size of the smallest sprocket. Regular touring freewheels had five sprockets, and the smallest sprocket had 14 teeth. Deluxe racing freewheels had six sprockets and the smallest sprocket had 13 teeth. SunTour and Shimano changed the pattern. Your small sprocket can now be as small as 11 teeth with a Shimano Dura-Ace Freehub or 12 teeth with Maillard, Regina, or SunTour freewheels. You can use the smallest sprocket with either racing or touring gearing arrangements. So in today’s multiple- choice world, you have to decide which small sprocket is right for you. You can get a 100-inch High gear with a 52-tooth chainwheel and a 14-tooth sprocket, or with 48 X 13, or 44 X 12, or 41 x 11, or even 55 X 15. To help you with your decision, I’ll explain the factors involved.

___ Higher Highs ___

A small fraction of the bicycling population needs a High higher than 100 inches. An even tinier group needs a High higher than the 108 inches you get with a 52-tooth chainwheel and a 13-tooth sprocket. Still, racing chainwheels with 56 and 58 teeth are made, and 115-inch gears are used by very strong time trialists. An 11-tooth Shimano Dura-Ace Freehub sprocket and a 52-tooth chainwheel give a high of 128 inches. For most people, the proper response is “So what?” If you like to pedal downhill at 45 mph or you have long cranks or a slow cadence, you might occasionally use an “overdrive” gear of 110 or so. Most riders are better advised to save their knees and speed up their cadence. I have a 118-inch High and a 108-inch 17th gear on my loaded touring bike, but I use them only about 5 percent of the time. Shimano sells a few 11-tooth sprockets to racers for the downhill side of hilly stages. The 12-tooth sprocket has become the racing standard since it became readily available.

FIG. 1 Freewheel sprocket tooth profiles.

===

TABLE 1. Freewheels: Smallest Sprocket; Largest Sprocket; Tooth

1. The weights shown are for 14-17-20-24-28 sprockets on the 5-speed freewheels, 14-16-18-21-24-28 sprockets on the wide-spaced 6-speed freewheels, 13-14-15-16-17-18 sprockets on the narrow-spaced 6-speed freewheels, and 12-13-14-15-16-17-18 sprockets on the narrow-spaced 7-speed freewheels. The Shimano Freehub and Maillard Helicomatic weights include the weight of a small-flange, 126mm hub. Subtract about 330 grams to compare these weights with those of conventional freewheels.

2. See figure 1 for the tooth profiles. Sym = symmetrical, or teeth with a chamfer on both sides and a flat top; Asy = asymmetrical, or teeth on the small sprockets have a chamfer on both sides, while teeth on the large sprockets have a chisel profile with the chamfer on the inside. Tw = twist-tooth, or teeth chamfered on the inside and twisted clockwise; AsyZ = asymmetrical zigzag, which is the same as asymmetrical except that the teeth on the largest sprockets are set alternately left and right.

3. Remover symbols: Sp = splined; 2N = two notches; 4N = 4 notches.

===

______ Less Weight ______

The weight saving possible with small sprockets and chainwheels appeals to me. It makes more sense than drilling holes in highly stressed components. An alpine gear train using a 52/40 crankset and a 14-17-20-24-28 freewheel weighs about 1 pound, 13 ounces (810 grams). The same gear train using a 41/32 crankset and an 11-13-15-18-22 freewheel weighs about 1 pound, 4 ounces (570 grams). You save more than ½ pound, and you save even more if you use a racing instead of a touring rear derailleur.

My wife doesn’t like triple shifting but she wants a low Low. Her bike is an ultra-wide 12-speed using a 40/28 crankset and an 11-13-15-18-24-34 Shimano Freehub. The biggest problem we had with this setup was finding a front derailleur that mounted low enough and cleared the chainstay. Her gear train has been in service for five years.

________ Chordal Action _________

The mechanical engineering textbooks recommend 16-tooth minimum sprockets for maximum efficiency and chain life. At 400 rpm, a 14-tooth sprocket can transmit 50 percent more horsepower than an 11-tooth sprocket.

However, bicycle gear trains are not industrial chain drives and sound engineering principles don’t necessarily apply. The main problem with very small sprockets is “chordal action.” The sprocket isn’t completely round so the chain moves with a jerky action. The uneven movement amounts to 2 percent for a 16-tooth sprocket, 3 percent for a 13-tooth and 4½ percent for an 11-tooth sprocket. I can’t detect the chordal action in my 11-tooth gear trains. Small- wheel bicycles like the Moulton AM-7 use tiny sprockets to avoid monster chainwheels. At the International Human Powered Vehicle Association finals, the Moulton entry used a 10-tooth sprocket to go 50 mph at a cadence of 120. They had a 9-tooth sprocket in reserve, if the rider had needed it.

___ High Chain Force and High Tooth Wear ___

As you reduce the diameters of the sprockets and the chainwheels, the chain tension must increase to transmit the same power. An 11-tooth drivetrain stresses the chain 27 percent more than a 14-tooth drivetrain. The answer seems to be to make stronger chains. The Sedisport Pro, Regina CX, and Shimano Dura-Ace racing chains are among the strongest made.

The higher chain forces work against fewer teeth. Without question, smaller sprockets wear out faster. The response has been to make the small sprockets out of very hard alloy steels. I’ve been using 11-tooth sprockets for more than six years and I’ve only worn a small hook in one or two. However, I’m more of a spinner than a masher and only use my highest gears to pedal down hills.

____ Tooth Jump ____

Tooth jump is the most severe problem that you encounter with tiny sprockets. I suspect it’s the main reason that so few professional racers or tandems use 1 1-tooth sprockets. It’s unpleasant when you’re really stomping on the pedals to have the chain jump a tooth or two and the pedal fall a couple of inches. To avoid tooth jump, the rear derailleur should position the jockey pulley close to the sprocket and well forward. This provides more chain wrap.

Summing up, if you have a 14-tooth freewheel and you’re happy with your High, stick with it. If you’re buying a new crankset and a new freewheel for loaded touring or for sport touring, you might as well order a freewheel with a 13-tooth small sprocket. The benefits exceed the demerits. If you’re buying a racing freewheel, buy a 12- or 13-tooth small sprocket depending on how high you want your High (11-tooth sprockets are still pretty much a gear freak’s specialty item). Keep the size of your large chainwheel between 45 and 52 teeth. If you find that you never use your High, install a 15-tooth sprocket to give you a useful High.

___ Largest Large Sprocket ____

Choosing the largest freewheel sprocket is more straightforward than choosing the smallest. The economical way to get a lower Low is to install the largest sprocket that your freewheel (or rear derailleur) will handle. Regina makes a 31-tooth sprocket, Maillard a 32-tooth sprocket. (The Maillard sprocket board has a place for a 34, but they are very rare.) Shimano makes a 34-tooth sprocket for both Freehubs and regular freewheels. Dura-Ace and 600 EX sprockets top out at 28 teeth, but the lower-priced sprockets are completely interchangeable except for color.

SunTour is special. They make a 38-tooth AG (alpine gear) sprocket that requires a special AG rear derailleur. It’s most useful for economy Lows on bicycles like the Schwinn Varsity, which has a 39-tooth inner chainwheel. No smaller chainwheel is available and it doesn’t make economic sense to install a new crankset. You can get a 31-inch Low with a 34-tooth sprocket. If that isn’t low enough, you can get 28-inch Low with the 38-tooth sprocket. Shifting with the AG rear derailleur is good but not excellent.

SunTour now makes 34-tooth sprockets for all of their freewheels. They used to play games with the gear freaks. They made 34s for their low-priced Perfect/Pro-Compe freewheels but only 32s for their top-quality Winners. The Perfect splined sprockets had slightly deeper splines, so you had to file them a bit to use them on a Winner. Old SunTour Perfect large sprockets had an excessive amount of set on their zig-zag teeth and they worked poorly with narrow chains.

The main reason not to use a 34-tooth sprocket is indexed shifting. So far, both Shimano and SunTour are limiting their rear derailleurs to 32-tooth sprockets in the index mode. In the nonindex mode, today’s touring rear derailleurs shift like gangbusters on the “buzz saws.” If your gear scheme only involves a 31- or 32-tooth large sprocket, buy a Shimano or SunTour freewheel anyway because the Japanese wide-range freewheels shift the best and you may want a lower Low in the future.

Mechanical Construction

The best mechanical design for freewheels calls for both a strong rear hub and a strong freewheel body. The two requirements often conflict (I talk about hub construction in section 11). The Shimano Freehub and the Maillard Helicomatic take a different approach. They integrate the hub and the free- wheel, which allows them to locate the hub bearings next to the dropout. This puts the load right next to the dropout and results in fewer broken axles. The integrated design requires that the hole in the smallest splined sprocket be bigger than the freewheel body. Shimano’s 11-tooth No. 1 sprocket and 12- tooth splined No. 2 sprocket means that the Freehub’s freewheel body is only 1.35 inches in diameter. Shimano has to go to special lengths to provide an adequate ratchet in this small diameter. The Helicomatic uses a more conventional freewheel design and its sprocket arrangement isn’t quite as flexible.

Designers of conventional freewheels face a different set of problems. As long as the smallest sprocket had 14 teeth, the freewheel body diameter could be designed to fit inside the 15-tooth splined No. 2 sprocket. When the market demanded 11-, 12-, and 13-tooth sprockets, there were problems. The makers solve these problems in different ways.

Some makers use a narrow 4-speed freewheel body and screw one or two of the outer sprockets onto the fourth sprocket. The small outer sprockets hang outboard of the large-diameter body. This stresses the outboard freewheel bearings and makes it harder to change sprockets. Other makers step the freewheel body and thread the small outer sprockets onto the small-diameter outer section. The larger-diameter middle sprockets thread or spline onto the larger-diameter section, which holds pawls, ratchet, and inboard bearings. Some bodies have three steps.

Ease of Changing Sprockets

The ease with which sprockets can be changed has two aspects. First, how easy is it to take off the old sprockets and install new ones? Second, how many sprockets do you have to own to cover your needs? Shimano Freehubs and Maillard Helicomatics win hands down on both points.

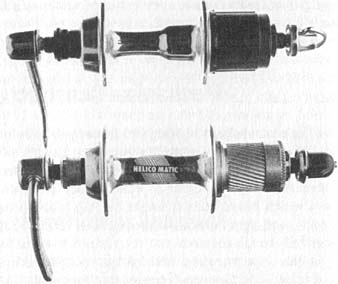

PHOTO 2 Freewheel-hub combinations: Shimano Freehub (top) and Maillard

Helicomatic (bottom).

______ Ease of Sprocket Removal ______

The most convenient design for easy sprocket changing has a threaded sprocket on the outside and splined inner sprockets. That’s how the Shimano Freehub works. You unscrew the small sprocket, zip on a stack of spacers and splined sprockets, and screw the small sprocket back on. The Maillard Helicomatic is similar. Both Maillard and Shimano let you pre-assemble the sprockets into a cassette, but this hasn’t been a big advantage.

The freewheels that pair the two small sprockets together are harder to work on. Basically, the more threaded sprockets and the more different thread diameters and spline diameters you have to deal with, the more difficult it is to change sprockets. If you’re buying a freewheel to incorporate your ultimate gear scheme, easy sprocket changes don’t matter very much. If you plan to change your sprockets every few months (or every race), then ease of changing sprockets is important. ( TABLE 1 rates this feature.)

________ Number of Sprockets Needed ________

If your freewheel has threaded pairs, different thread diameters, different spline diameters, and different tooth profiles for different positions on the freewheel, then few, if any, sprockets can be used in more than one position. Thus, if you want to be able to change sprockets for different events or different types of riding, you will have to purchase a range of sprockets for each position.

Sprocket Versatility:

Sprocket versatility involves four questions concerning the sprockets that are available for each particular freewheel. How small a smallest sprocket is available? How large a smallest sprocket is available? (This second concern is important to Junior racers who are limited to a 90-inch High or to people who want Highs in the 805.) How large is the largest sprocket? What intermediate sprockets are available in what positions?

SunTour offers six 15-tooth sprockets and four 16-tooth sprockets for use on the Winner Pro. (However, you can’t make a Winner Pro with a 16-tooth outer sprocket.) There are seven 15-tooth sprockets and six 16-tooth sprockets available for use on the Regina CX. By contrast, the Shimano Freehub has one threaded sprocket and one splined sprocket in each size and you can even make up a Freehub with an 18-tooth outer sprocket. ( TABLE 1 lists the number of sprockets found on each freewheel model, while TABLE 2 describes the type of sprockets used and the choices available for each position.)

Making a custom-built freewheel used to be harder because the widely available freewheels had limited sprocket versatility. Now you can make up almost any reasonable sprocket combination. However, only SunTour and Regina make 27-tooth sprockets. At 28 teeth and higher, you have to pick even numbers. And not all freewheels can be made up into a straight block.

== ==

TABLE 2. Sprocket Versatility

1. The sprockets are numbered from the outside to the inside, so Pos. 1 refers to the outer, smallest sprocket The designation 17-26,28,30,32 means that 17-, 18-19-, 20-, 21-, 22-, 23-, 24-, 25-, 26-, 28-, 30-, and 32-tooth sprockets are available for these positions.

2. Sprocket types indicate the sprocket arrangement from smallest to largest P = pair, a small, externally threaded sprocket mating with a larger, internally threaded sprocket; I = triple, three sprockets threaded together. Sm = small thread; LTh = large thread; SSp = small spline; MSp = medium spline; LSp large spline; ITh = internal thread; LHTh = left-hand thread (found only on Regina Oro large sprockets). 1-Sib, 2-SSp, 2-LSp means one small-threaded sprocket, t small-splined sprockets, and two large-splined sprockets.

== ==

_____ Weight _____

The freewheel is a big, heavy lump of metal, so its weight is important to the weight fanatics. As discussed earlier, one way to save weight is to use smaller sprockets and smaller chainwheels for the same gears. The other alternative is to make the freewheel body and the sprockets out of aluminum or titanium.

Currently, there are four alloy freewheels available: the Campagnolo C-Record, the Maillard 700 Course, the SunTour MicroLite, and the Zeus. The C-Record is very expensive. The Maillard and the SunTour are expensive and the Zeus is a bargain. If you buy an alloy freewheel, expect to change sprockets frequently because aluminum sprockets wear faster than steel sprockets. Of course if you can afford an alloy freewheel, you probably won’t worry about sprocket expense.

PHOTO 3 Range of freewheel sprockets: Shimano Dura-Ace Freehub, 11 to 16

teeth (upper right); Maillard 700, 12 to 17 teeth (upper left); SunTour Perfect,

14 to 38 teeth (bottom).

______ Bearing Seals _____

Conventional folklore says that you shouldn’t grease freewheels because the grease will harden and cause the pawls to hang up. Then along comes Phil Wood with his ingenious freewheel greaser. Phil assures me that Phil grease will not harden in a normal freewheel lifetime. I believe him, but I haven’t bought one of Phil’s grease guns yet. All four major freewheel makers say to oil and not to grease their freewheels.

I still treat my freewheels in the time-honored fashion. Every six months or so, I flush them out with kerosene and then I pour oil in the front until it comes out the back. Since oil doesn’t do much to keep water out of the freewheel body if you ride in the wet or in the outback, mountain bikers demand something better. Fortunately, the best of today’s freewheels include labyrinth seals to keep the oil inside and the water and dirt outside. This feature is shown in TABLE 1.

____ Tooth Hardness ____

The harder the teeth, the longer a sprocket will last before it develops a hook and has to be replaced. Worn sprockets and stretched chains cause poor shifting and chain jump. The small sprockets wear out first. Sprocket wear is the main argument against using freewheels with aluminum or titanium sprockets. You save weight but you have to replace the sprockets regularly. In TABLE 1, the numbers used to describe tooth hardness are taken from the C scale of the Rockwell hardness test. Teeth rated C-20 and below are relatively soft and short-lived, while those rated C-40 and above are relatively hard and long-lived.

_____ Type of Remover _____

There are two general kinds of removers, splined and notched. With a splined remover, there is less chance of gouging up the face of the freewheel body. There are two kinds of splined removers, solid and shell types. The solid models require you to completely disassemble the hub before you can remove the freewheel. The shell models fit around the outside of the axle cones, but they’re more delicate. Phil Wood makes a series of shell removers for those models that come only in solid versions. With a notched remover, use the quick-release skewer to make sure that the remover is securely locked into the notches. I try to have a remover for every freewheel that I’ve tested. At last count, I was up to sixteen. And you wonder that I’m just a bit paranoid about standardization.

_____ Freewheel Makers ______

In the other component sections, 1 cover only the components that are currently in production and are widely available in the aftermarket. Freewheels are an exception because you can still buy sprockets for obsolete freewheels. To help you decide between revising your present freewheel or buying a new one, I list both current and obsolete freewheels in tables 1 and 2, and also describe them below.

____ Maillard _____

Maillard makes three different brands of freewheels: Atom, Normandy, and Maillard. The Atom is the lower-priced model for the OEM market. The Normandy uses a 4-speed body and an outer two-sprocket pair. It has a large- diameter bore and is the lightest model. The top-of-the-line Maillard 700 won 11 straight Tour de France victories. The various models that bear this name are usually carried by the mail-order houses and bike shops. The Maillard 700 comes with an expensive all-alloy body or with a steel body. The 700 Course body can be made into wide-spaced 5- and 6-speed freewheels and the 700 Compact can be made into narrow-spaced 6- and 7-speed freewheels.

Maillard’s Helicomatic hub-freewheel has almost the same sprocket versatility as Shimano’s Freehub and in some ways (larger-diameter bearings and ratchet) it’s a superior piece of mechanical engineering. In the past, my main objection to Maillard was their old-fashioned sprocket tooth profile. Wide- range Maillard freewheels simply didn’t shift as well as their Japanese competition. I observed this on my derailleur testing machine and I could feel the difference out on the road. I once talked about this to their director general at the Long Beach Bike Show. He said that Maillard had built asymmetrical sprockets a Ia SunTour, but they couldn’t detect any difference and the European buyers preferred symmetrical sprockets.

Maillard freewheels and Sedis chains are now owned by Sachs-Huret, and the Huret ARIS indexed shifting system will use Maillard and Sedis. In 1987, Maillard provided chisel-shaped teeth on their largest sprockets. In 1988, they Introduced a brand-new ARIS tooth profile.

____ Regina ___

There are three series of Regina freewheels: Extra/Oro, Extra-BX/Oro-BX, and CX/CX-S. Extra and Oro are quality designations. They’re essentially the same except that Oro sprockets are brass plated. I recall an apocryphal story about the Regina inspector standing in front of two boxes spinning freewheels. The extra-smooth ones went into the Oro box and the rest went into the Extra box.

Extra/Oro is out of production. It’s an antique design that’s been around for 40 years. Milremo and Atom used to make lower-priced Oro clones but they’ve passed away. It’s very hard to change sprockets on these freewheels because all of the sprockets are threaded. The two largest sprockets have left-hand threads and you have to remove the freewheel and lock the body with a special tool to change the big sprockets.

The main reason that this freewheel survives is that there are so many of them (and Atoms and Milremos) still in service and so many bike stores have sprocket boards. That’s a considerable investment since there are 59 different sprockets on a full board. There’s even a special “Scalare” body to allow making up a 13-14-15-16-17 straight block. The 6-speed Oro uses a triplet. The little sprocket screws into the second sprocket, which screws into the third sprocket, which (finally) screws on to the body. Today, there’s no good reason to buy an old Extra/Oro freewheel, but if you have one, you might decide to change the sprockets.

Regina replaced the old Extra/Oro series with the Extra-BX and the Oro BX. In 1987, the BX models were upgraded for indexed shifting. The upgraded version, called Synchro, has chisel-shaped teeth and uniform sprocket spacing. These are modern designs with one threaded sprocket and two sizes of splined Sprockets in the 5-speed model and a two-sprocket pair in the 6-speed model. Synchro is made only in wide-spaced versions. This is the freewheel to use if you build a do-it-yourself indexed system with Campagnolo’s Syncro levers.

The CX and CX-S are Regina’s modern, top-of-the-line freewheels. They’re very similar to the SunTour Winner. One body lets you make up wide and narrow 5-, 6-, and 7-speed freewheels. The wide-spaced 5- and 6-speed versions are called CX and the narrow-spaced 6- and 7-speed versions are called CX-S. They have all of the complexity of the Winner and then some. Regina added an extra threaded sprocket in the middle. There are 47 different sprockets and five different spacers on the sprocket board. The CX and CX-S use symmetrical sprockets in all sizes. The America is a special version of the CX and CX-S with a plastic bearing seal. It comes in a neat can that you use for cleaning and oiling.

_________ Shimano ________

Shimano makes freewheels in four different price-quality levels for the aftermarket: Dura-Ace, Sante, 600 EX, and the Z series. Shimano currently imports Dura-Ace and Deore XT Freehubs into the USA. Shimano avoided narrow-spacing until 1987. Now racers can get indexed shifting, narrow-spaced 7-speed Sante and Dura-Ace freewheels with sprockets available from 12 to 28 teeth. The Sante and Dura-Ace freewheels are identical except for the finish of the sprockets. Shimano does not believe in sprocket pairs. On the Dura-Ace and Sante freewheels, the small outer sprocket threads into the body rather than into the No. 2 sprocket.

Thanks to their twist-tooth profile, all of Shimano’s freewheels and Freehubs are superior shifting, particularly with Uniglide chains. Shimano free- wheels and Freehubs have a minimum number of different kinds of sprockets. It’s easy to change sprockets and it requires a minimum number of sprockets.

Shimano Freehubs are the gear freak’s favorite because of the ease of changing sprockets and their sprocket versatility, from an 11-tooth (Dura-Ace) or 12-tooth (all other models) smallest sprocket all the way to a 34-tooth largest sprocket. There are five or six different Freehub models but Shimano is currently only importing Dura-Ace and Deore XT Until 1987, all Freehubs were wide-spaced 5- or 6-speeds. (Shimano made a wide-spaced 7-speed Dura-Ace AX Freehub in the aerodynamic age. Now it’s a collector’s item.)

In 1987, Shimano decided that the racers wanted 7-speed SIS. So they came out with narrow spacers and narrower threaded small sprockets. You can now make the Dura-Ace Freehub into either a wide-spaced 6-speed or a narrow- spaced 7-speed. The early (1981) Freehubs had mechanical reliability problems. Over the years, Shimano has made frequent modifications so that the Freehub is now one of the most reliable units available.

_____ SunTour _____

SunTour currently makes four freewheel models: Winner Pro, Winner, Alpha, and Perfect. SunTour dominates the low-priced freewheel market. There are probably more low-priced Perfect and Pro-Compe freewheels in use than everything else combined. (These two models are the same except for the Pro Compe’s gold-plated sprockets.) Over the years, the Perfect and Pro-Compe have improved in quality, but they haven’t changed in essential detail since SunTour entered the U.S. market in the early 1970s. There are two threaded sprockets and three splined sprockets on the 5-speed model. There used to be a variety of wide- and narrow-spaced 6-speed models as well.

PHOTO 4 Narrow-spaced 7- speed freewheel bodies: top to bottom, Regina

CX-S, Shimano Dura-Ace, and SunTour Winner Pro.

Right from the start, SunTour used a symmetrical tooth profile on the threaded sprockets and an asymmetrical profile on the large splined sprockets. In the late 1970s, they provided zigzag teeth with a distinct set—one left, one right—on the largest sprockets. This interfered with the shifting of narrow- spaced chains and SunTour reduced the amount of set. SunTour makes a 38- tooth sprocket for the Perfect series. It gives you an idea of the impact of the indexed shifting revolution, that SunTour is replacing Perfect and Pro-Compe with a new Alpha series. Alpha is a low-priced, wide-spaced 6-speed freewheel similar to the old Pro-Compe.

SunTour made substantial revisions to their freewheels in 1987 to accommodate AccuShift. You can tell the AccuShift-compatible models because they have four notches for a four-notch remover. SunTour’s top freewheels, Winner Pro and Winner, were little changed, but the narrow-spaced 6-speed versions will no longer be sold. Narrow-spaced 7-speed Winner freewheels have uneven spacing: The smaller sprockets are wider-spaced than the larger ones. SunTour designed the AccuShift shift levers to match the uneven spacing.

SunTour developed and marketed the first narrow-spaced freewheels, known as “Ultra” type. SunTour Ultra-6, wide-range freewheels shift better with narrow spacing and narrow chains than any others. SunTour’s top-of-the-line freewheel has progressed from Winner to New Winner and back to Winner and Winner Pro. The Winner Pro has an excellent labyrinth seal to keep out water.

The current Winner series was designed to let the bike shops build up wide and narrow, 5-, 6-, and 7-speed freewheels with just one body. It’s a complicated system. There are 41 sprockets and seven spacers on the Winner sprocket board, It’s absolutely essential that you use SunTour’s chart when you assemble a Winner. I’ve answered dozens of letters from people who have misassembled their Winners, turning them into losers. I once calculated that there are 534,287 wrong ways to assemble a 6-speed Winner, and only 1 right way.

SunTour tries to keep some sprocket interchangeability between their different models and between new and old models. In the 1986 metamorphosis from New Winner to Winner/Winner Pro, the second set of threaded sprockets went from large-threaded to small-splined. SunTour both threaded and splined the Winner Pro body so the shops could use up their old stocks. You can use the Perfect/Pro-Compe splined sprockets, including the 38-tooth “buzz saw,” on the Winner bodies.

PHOTO 5 Wide-spaced freewheel bodies: top to bottom, Maillard 700 Course

(5- or 6-speed); Regina Oro BX (5- or 6-speed); Regina America (6-speed);

Shimano MF-Z (6-speed); and Maillard Helicomatic (5-speed).

_____ Everybody Else _____

Everybody else consists of two aluminum-bodied freewheels made by Campagnolo and Zeus. Campagnolo introduced their ultra-light, 6- or 7-speed C-Record freewheel in 1983. Symmetrical profile sprockets are available in sizes ranging from 12 to 28 teeth. Cost for this freewheel runs around $200 for the 13- tooth version. The 12-tooth version uses two titanium sprockets, which adds an extra $100 to the price. Campagnolo provides a $500 tool kit in a plushly lined hardwood box to properly service their freewheel. Campagnolo replacement sprockets are priced accordingly.

At the other end of the alphabet and the price spectrum, Zeus makes the least expensive alloy freewheel. It comes in wide-spaced 5- and 6-speed and narrow-spaced 7-speed versions. The small sprockets are steel. Sprockets are available from 13 to 30 teeth. The 5-speed model’s smallest sprocket has 14 teeth. Prices run in the $75 to $100 range.

_____ My Favorite Freewheel ____

Picking my favorite freewheel is easy. It’s the Shimano Dura-Ace Freehub hands down for both racing and loaded touring. It has the best shifting tooth profile, and it’s strong and reliable because of the wide-spaced hub bearings. It’s also adequately sealed against water. The sprocket versatility and the ease of changing sprockets on this freewheel is the best available. I have nine Freehubs on the bicycle fleet.