. You can upgrade your bicycle’s gear train by converting to indexed shifting. It will let you shift on the rear just by moving the shift lever to the next setting. It will also make it much easier for you to shift while you’re pedaling uphill.

Indexed shifting is a greater Improvement over manual shifting than push button radio tuning is over manual tuning. If you’re upgrading your gear train, consider one of the new indexed shifting packages. Test ride a friend’s bicycle and it may convert you.

I have placed all of the significant background on indexed shifting in this section rather than scattering it through the rear derailleur, freewheel, and chain sections. In my discussion of shift levers, I cover both indexed and conventional friction types.

________ Indexed Shifting ________

In 1985, Shimano perfected a reliable Indexed shifting package, which they called Shimano Index System or SIS. It was a genuine breakthrough in shifting performance. It took two years for the $15 to trickle down from Dura-Ace to Shimano’s lower-priced lines, but by 1987, the U.S. market was sold on the benefits of indexed shifting. SunTour Introduced the AccuShlft package and Campagnolo introduced Syncro shift levers for the 1987 market, and Huret Introduced their Advanced Rider Index System (ARIS) in 1988. A new bicycle limply won’t sell in today’s market lilt doesn’t have indexed shifting. Only the highest-priced racing bicycles and the least expensive gaspipe bicycles now come with friction shift levers.

It takes more than a new set of shift levers to convert a bicycle to indexed shifting. Reliable indexed shifting is a cooperative venture between rear derailleur, freewheel, chain, and shift lever. Shimano and SunTour have designed the various components of their indexed shifting packages to work as a unit. If you don’t use the specified parts, you may not get top performance. (Such specialization of componentry has taken some of the fun out of gear freaking.)

The necessary parts of the indexed shifting packages are being sold as upgrade kits. These kits usually include indexed shift levers, front and rear derailleurs, freewheel, chain, cables, and casings. You may or may not be able to use your old freewheel, depending on its sprocket shape and spacing. Even if you end up with an extra freewheel, the upgrade kit is a much better buy than the separate parts. If you opt for indexed shifting, your choice is between the various Shimano and SunTour models, or a do-it-yourself approach with Campagnolo’s Syncro levers. Out on the road, the differences between systems are relatively minor, though Shimano has two extra years of development and SIS is more forgiving of wear or mis-adjustment than the other systems.

Indexed shifting has separated the component makers into haves and have-nots, and the have-nots may not survive. Shimano, SunTour, and Campagnolo are survivors. Sachs-Huret has developed their ARIS package for the 1988 model bicycles. Sedis and Maillard are now part of Sachs-Huret. This allows Sachs-Huret to market a complete French gruppo. As I write this, Simplex has gone into bankruptcy and is merging with Ofmega. No Simplex or Ofmega indexed shifting package has been announced. I hesitate to predict the future for the rest of the derailleur makers.

________ Factors Affecting Rear Shifting ________

It has taken me a long time to sort out the reasons that make some gear trains shift more precisely than others. It’s a complex multi-variable problem. There are more than a dozen factors involved and they interact with each other. In an ideal rear shift, the shift lever acts like a trigger. You move the lever to the shift point and the chain jumps to the next sprocket; it’s precisely lined up, so no additional lever movement is necessary. Think about it and you’ll realize that I’ve just described indexed shifting, which requires a nearly ideal gear train.

I’ve divided the factors that affect rear shifting into four main categories: rear derailleur, freewheel, chain, and shift levers. Some general factors don’t fit neatly into the four categories, so I’ll cover them first.

____ General Factors _____

There are a variety of general factors that affect the shifting on a bicycle. We will now examine them one by one.

Upshifts (Drops) and Downshifts (Climbs)

Some terminology: Upshift and downshift are confusing terms. I use upshift to mean shifting up to a higher gear, so you can go faster. When you upshift on the rear derailleur, the chain moves down from a larger to a smaller sprocket. In this section I’m going to call an upshift on the rear a “drop,” and a downshift on the rear a “climb.” To climb a hill, your rear derailleur causes the chain to climb onto a larger sprocket.

It’s fairly easy to drop from a big sprocket to a smaller one. The jockey pulley levers the chain off the larger sprocket and it drops naturally to the next sprocket. It’s much harder to climb from a small sprocket to a larger one. The jockey pulley and the rear derailleur cage bend the chain inward until the side of the chain meets the larger sprocket.

Like a blind date, the meeting of chain and sprocket can generate engagement or resistance. If the protruding pin or the corner of the chain runs into the teeth of the large sprocket, then the chain will climb smoothly onto the larger sprocket. On the other hand, if the flat side of the chain runs into the flat side of the larger sprocket, then the sprocket will act like a spoke protector and the chain will stay put. So you pull harder on the shift lever and the chain pushes harder against the big sprocket until the shift finally takes place, with much noisy mechanical sadism.

Shifting to the lowest gears takes extra skill because you’re on a hill and you have to shift quickly before the bicycle slows down.

Hanger Drop

The derailleur hanger is the tab of metal that hangs on the right hand rear dropout. It’s also called the tab or the dropout. Inexpensive bicycles don’t have a built-in hanger so inexpensive rear derailleurs come with a separate derailleur hanger. The derailleur designer assumes that the derailleur will be mounted in a given position relative to the rear axle. His design then locates the jockey pulley relative to the rear axle. If you use a different hanger than the one the designer used, your rear derailleur may perform differently than the designer intended.

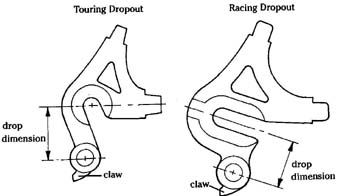

There’s quite a variation in hangers but they generally fall into racing and touring categories. A racing hanger has a drop of about 1 inch. A touring hanger has a drop of about 1 ‘4 inches. If you mount a touring rear derailleur on a racing hanger, it may not be able to handle the largest freewheel sprocket. If you mount a racing rear derailleur on a touring hanger, it won’t shift as crisply as it should on the small sprockets. (The differences between racing and touring dropouts are shown in FIG. 1.)

Chain Tension:

The top half of the chain is tensioned by your pedaling.

This affects front shifting, which is why you relax the pedaling force when you shift. The spring of the rear derailleur’s cage pivot tensions the lower half of which has a modest effect on rear shifting.

Cable Stretch—Casing Compression:

Cable stretch, casing compression, binding, and friction all cause the derailleur to take a different position than that called for by the indexed shift lever. Each maker has come up with a different answer. Campagnolo uses an oversized wound cable for minimum stretch. Shimano uses an oversized braided cable. SunTour uses a smaller- diameter wound cable for minimum friction and binding. Casings should be made of square wire to minimize compression and they should be lined to minimize friction. The best liners are molded into the wire to increase rigidity.

Braze-On Bosses for Down Tube Levers:

Campagnolo-pattern braze- on bosses, with the flats parallel to the down tube, have become the industry standard. If the flats are at right angles to the tube, you’ll have to use friction levers or Shimano 600 EX/SIS levers, which work with either alignment. Shimano makes a special “B-Type” braze-on adapter that lets you mount the shift levers on top of the down tube, rather than on the sides.

____ Rear Derailleur Design ____

FIG. 1 Rear derailleur hangers. Touring Dropout; Racing Dropout; drop dimension

FIG. 1 Rear derailleur hangers. Touring Dropout; Racing Dropout; drop dimension

Indexed shifting requires a precise-shifting rear derailleur. After the shift, the jockey pulley must be centered under the sprocket. You can move a friction shift lever a tad to quiet the coffee grinding but the indexed lever can’t do this line-tuning. The following rear derailleur features affect shifting performance.

Jockey Pulley to Sprocket Distance (Chain Gap):

The rear derailleur should maintain a chain gap of 1 to 2 inches—or two to four links of chain— between the jockey pulley and the sprockets in every gear. A longer chain gap will cause the jockey pulley to move more than one space before the chain derails to the next sprocket. I call this excessive movement “late” shifting. After each shift, you have to reverse the shift lever to center the jockey pulley and quiet the grinding at the back. Late shifting is an unpleasant derailleur characteristic. Late-shifting derailleurs sometimes shift two gears at once, or they shift back to the original gear when you reposition them. Late-shifting derailleurs are also reluctant to shift under load.

A short chain gap causes the shift to take place before the jockey pulley has moved far enough. You have to push the lever a bit farther after the shift. I call this “early” shifting. It’s not nearly as unpleasant as late shifting. You often push the lever a bit too far anyway. There’s a “quiet zone” about 1/32-inch wide on each side of the centered position. If the chain ends up in this zone, it will run quietly. For smooth, reliable indexed shifting, a rear derailleur should shift a bit early. When the shift lever moves to the detented position, it will center the jockey pulley.

Shimano, SunTour, and Huret have concluded that rear derailleurs with two spring-loaded pivots and a slanted parallelogram are the best design to provide a uniform chain gap. The new Shimano and SunTour indexed shifting rear derailleurs look the same, though they perform differently. Shimano de signed for a very short chain gap to shift early in every gear. SunTour’s derailleurs are more traditional and their chain gap is a bit greater. SunTour has designed their shift lever to compensate for late shifting.

Derailleur Rigidity

Beefy derailleurs with rigid pivots and parallelograms bend less under the strain of shifting, so they shift more precisely. The current crop of mountain bike rear derailleurs is very rigid. They shift better and last longer than the old flexible touring rear derailleurs.

Floating Jockey Pulley

Shimano designed the SIS rear derailleurs with a “Centeron” jockey pulley that can float back and forth so the chain can center itself in the quiet zone. Shimano can use a self-centering pulley because all the rest of the SIS gear train has very tight tolerances.

________ Freewheel Design ___________

The following freewheel factors affect rear shifting:

Tooth Difference between Adjacent Sprockets

When climbing to a lower gear, the jockey pulley bends the chain sideways until the chain runs into the larger sprocket. If there’s less than a 3-tooth difference between the sprockets, the chain will encounter teeth. If there’s more tooth difference, the chain will run into the flat side of the bigger sprocket, which looks like the spoke protector. This causes reluctant late shifting. Racing derailleurs have an easy task shifting over narrow-range racing freewheels. Any average design will work quite adequately. A touring, 13- to 34-tooth freewheel has a much more demanding task and only the best touring derailleurs climb well on the big sprockets. A 4-tooth difference is the break point between easy shifting and hard shifting.

Narrow- versus Wide-Sprocket Spacing

Sprocket spacing is tricky. The problem with a narrow-spaced gear train isn’t the narrow chain, it’s the narrow spacing between the freewheel sprockets. The space is just wide enough for the narrow chain so that as soon as the chain bends, it runs into the side of the adjacent sprocket. If the tooth difference is four teeth or more, the chain is trapped in the valley. Now you know why your old narrow-spaced 18- speed touring bike shifts so badly.

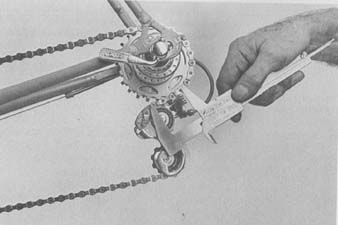

PHOTO 1 Chain gap on a Shimano Dura-Ace rear derailleur.

A wide-spaced freewheel has more clearance, even with a wide chain. The extra clearance lets the chain bend at a sharper angle so that it can come to grips with the larger sprocket. Narrow chains usually shift a bit better than wide chains on wide-spaced freewheels because they can bend farther. Shimano and SunTour have both decided that narrow-spaced 7-speed freewheels are for racers and wide-spaced 6-speed freewheels are for tourists.

Freewheel Sprocket Cross Section

For ten years, there’s been a little Sino-European war going on. The Japanese freewheel companies made odd- shaped teeth that reached out and snagged the chain on climbs. Every other year, they made something a bit different, each time labeled with a new buzzword. The European freewheel companies made symmetrical, tapered teeth that avoided intimate physical contact with the chain. Maillard and Regina said that it didn’t make any difference, and it didn’t make very much difference on racing freewheels with small tooth differences. With wide-range freewheels, however, symmetrical teeth shift poorly. Indexed shifting was the modern version of the Battle of Tsushima and you war historians know who won.

Shimano’s twist-tooth design twists each tooth so that the edge of the tooth sticks out waiting to snag any chain link that comes near. SunTour uses chisel-shaped teeth, flat on the outside and tapered on the inside on the middle sprockets. The large SunTour sprockets are “set” like a circular saw. Maillard and Regina started to provide chisel-shaped teeth on their larger sprockets in 1987. Maillard (Huret) developed a unique tooth profile for the 1988 ARIS freewheel. The teeth are narrower and higher at the rear. Shed a tear for the well-equipped pro bike shop with two or three sprocket boards full of expensive, obsolete sprockets.

PHOTO 2 Chain clearance: top, narrow Sedisport chain in a narrow-spaced

free- wheel; bottom, wide Uniglide chain in a wide-spaced freewheel.

_______ Chain Design ________

The following chain features affect shifting performance.

Chain Flexibility

The chain’s flexibility works with the rear derailleur’s chain gap distance to provide exact shifting. A stiff chain needs more distance.

A flexible chain needs less distance. Narrow chains are usually more flexible than wide chains. With indexed shifting, the designer has to know the flexibility of the chain. That’s why Shimano and SunTour recommend so few chains.

Chain Side Plate Shape

Most of the current derailleur chains have bulged, flared, or cutaway side plates to improve shifting. Certain chain designs work better with certain freewheel sprocket profiles. Chain side plate design is discussed in detail in section 9, so I won’t say anything more about it here.

Chain Width

Wide chains have more pin protrusion than narrow chains, which helps shifting. Wide chains can’t bend as much before they run into the adjacent sprocket, which hinders shifting.

______ Indexed Shift Levers _______

At this point, I can talk about the indexed shift levers. Writing this part of the indexed shifting story involved “reverse engineering.” I sat in my workshop with the finished components and my calipers and tried to figure out what the designers had in mind. (Military intelligence officers do the same thing with captured enemy equipment.) Shimano, SunTour, and Campagnolo each took a different approach to indexed shifting, and each approach shows in the shift lever design.

Cable Travel

A bicycle shifting system is a bit like the “Dry Bones” song. The shift lever’s connected to the cable drum, the cable drum’s connected to the derailleur cable, the derailleur cable’s connected to the parallelogram, the parallelogram’s connected to the derailleur cage, the derailleur cage’s connected to the jockey pulley, the jockey pulley’s connected to the chain, the chain’s connected to the sprocket, and the sprocket’s connected to. . . (I hear the word of the Lord).

Cable travel is the common denominator between the design of the indexed lever and the design of the rear derailleur. The cable travel required to shift over a 5-, 6-, or 7-speed freewheel varies between ½ and ¾ inch, depending on the width of the freewheel and the design of the rear derailleur.

In a perfect world, all rear derailleurs would shift early and there would be no friction, cable stretch, or casing compression. Leaving out these complicating factors, you could measure the components and calculate exactly how much cable travel is required to move the jockey pulley over the span of the free wheel. Then you could design the detents of the indexed shift lever to provide the necessary cable travel.

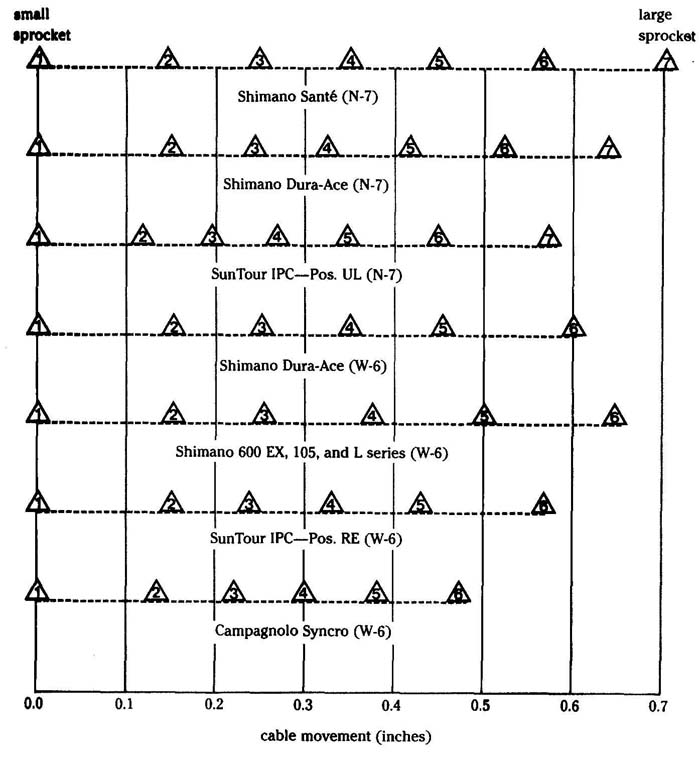

Campagnolo, Shimano, and SunTour designed their shift levers for a range of gear trains. I measured the cable travel of eight indexed shift levers and plotted the results in FIG. 2.

FIG. 2 Indexed shift lever cable travel.

Looking at the levers for wide-spaced 6-speed freewheels, the cable travel varies from 0.47 inch for the Campagnolo Syncro lever to 0.66 inch for the Shimano 600 EX and 105 levers, and L-series levers. You shouldn’t be surprised at the variation because there’s so little standardization in the bicycle business. If you are thinking about adding indexed shift levers to your present gear train, your main problem will be matching the cable travel of the shift lever and the rear derailleur. TABLE 1 shows the total cable travel for eight of the ten indexed shift levers listed.

Look closely at FIG. 2, because it tells you a lot about indexed shifting. Position 1 is the smallest sprocket, position 2 is the next larger sprocket, and so on. All of the indexed levers provide an extra-large first step. This allows the cable to be slack in the first position, to make sure that the chain will drop onto the small sprocket. The derailleur high gear stop keeps the jockey pulley from moving too far out. The extra cable travel takes up the slack in the first climb.

Following the step from position 1 to position 2, there are three (or four) smaller steps, but they’re not uniform, at least not on the Shimano and SunTour systems. The higher steps are a bit larger to compensate for cable stretch and for the nonlinearity of the rear derailleur. These intermediate steps are more critical than the end steps because the jockey pulley is located by the indexed lever, rather than by the derailleur stops. TABLE 1 shows the cable travel for the intermediate steps between the second smallest and the second largest sprockets.

Finally, there’s an extra-large last step to haul the chain up onto the largest sprocket, which is often a difficult shift. The derailleur low gear stop keeps the jockey pulley from moving too far in.

Late Shifting—Overshifting

Not all rear derailleurs have shifted when the jockey pulley arrives under the next sprocket. Sometimes, the chain is still grinding and grumbling away between the sprockets. With friction levers, you pull the lever a bit farther to finish the shift and push it back to re-center. This, of course, is the classic pull too far—push back drill for late-shifting derailleurs. The indexed shift lever can do the same thing with built-in lost motion. SunTour AccuShift levers move about 40 percent past the centered point before they click. The lever pops back when you release it. This technique only works on climbs. All indexed gear trains have to shift early on drops.

The original 6-speed Dura-Ace/SIS lever had about 25 percent built-in overshift, but the second generation SIS levers are different. They only overshift about 10 percent. The Campagnolo Syncro lever overshifts about 15 percent, but you can push it beyond the click point to finish the shift. I show the amount of built-in overshift in TABLE 1.

Finally, if the lever clicks before the shift occurs, you can keep moving the lever until you feel the shift. I think this defeats the whole idea of foolproof indexed shifting. When this happened on my SIS-equipped bike, I stopped and tightened the cable tension. You can only move the lever past the click point on climbs. On drops, the lever will go to the next click point.

With SIS and AccuShift levers, there’s a noticeable increase in lever effort --before you climb to the next position. I measured the amount of manual overshift before you feel this tactile stop and this is shown in TABLE 1.

Built-in and manual overshift are significant differences between the different indexed levers, because they limit your options in rear derailleurs, free wheels, and chains. SIS allows you to push the lever to the next position with the pedals stationary and release it. The shift occurs when you pedal. This is a very severe test that reveals the inherent differences between the various indexed shifting systems.

_______ Indexed Shifting Makers _______

A component company needs extensive resources to develop an indexed shifting package. Thus, it is no surprise that in 1989 only Shimano and SunTour made complete indexed shifting packages and Campagnolo had only Syncro shift levers. Sachs-Huret (no w SRAM) brought out their ARIS indexed package in 1988.

______ Shimano ________

Shimano spent the first five years of the 1980s getting ready for indexed shifting. By 1985, they had the pieces in place. Two outside ideas finalized their package: SunTour’s slant parallelogram for the rear derailleur and Sedis’s bushingless chain design for the Narrow Uniglide chain.

Shimano introduced indexed shifting with the top-of-the-line Dura-Ace because top-quality bicycles generally have better aligned dropouts and the riders generally take better care of their equipment. Shimano listened carefully to the feedback from the race teams and the bike shops and there were no serious problems. In 1986, Shimano moved down one price level with 600 EX/SIS. Again there were no major problems in a much broader market.

Shimano resisted narrow-spaced freewheels until 1987. Noting that most professional racers were using narrow-spaced 7-speed freewheels, Shimano developed 7-speed SIS prototypes and tested them on the Shimano-sponsored teams in 1986. By 1987, they had developed the following SIS models: the narrow-spaced 7-speed Dura-Ace for the racers, Sante for the sport tourers, and Deore for the mountain bikers. At the same time, 105 and the SIS compatible freewheels in the L series made indexed shifting available at lower price levels.

All SIS versions are designed around early-shifting rear derailleurs, twist- tooth freewheel sprockets, flexible Narrow Uniglide or Sedisport chains, and either narrow-seven or wide-six freewheels.

SIS gear trains are designed to shift early in every gear. Even with friction and mis-adjustment, climbs and drops take place before the shift lever clicks. SIS levers have very little built-in overshift and you shouldn’t have to push an SIS lever past the click point. Because of the early-shifting gear train and the minimum lost motion in the shift lever, Shimano ended up with a considerable tolerance in their SIS. They have used this tolerance to provide a self-centering Centeron jockey pulley. The Centeron pulley is the icing on the SIS cake.

Shimano makes six different down tube indexed levers, four wide-sixes and two narrow-sevens. The 600 EX, 105, and L-series levers are interchangeable. The old Dura-Ace wide-six, Dura-Ace narrow-seven, and Sante narrow-seven are unique. The 1988 600 Ultegra (replaces 600 EX) offers a choice of wide-six or narrow-seven.

_____ SunTour ______

Through 1985, SunTour hoped that indexed shifting would be another Shimano fad. By early 1986, it was obvious that indexed shifting had caught on. When SunTour set out to develop AccuShift, they faced a nasty series of problems. Their freewheels had three different tooth profiles for the different sprocket positions and the small sprockets weren’t evenly spaced. SunTour’s old single-pivot rear derailleurs provided different chain gaps in the various gears so they shifted at different jockey pulley positions. These problems didn’t matter in a non-indexed world—you just moved the lever a bit more or less, but they were critical with indexed shifting.

SunTour moved decisively. First, they discontinued their narrow-spaced 6- speed freewheel, which had the worst spacing variations. Next, they made the sprocket spacing uniform on their 5- and 6-speed freewheels. (You can tell the new SunTour freewheels with uniform spacing because they have four notches for a four-spline remover.) SunTour then redesigned all of their rear derailleurs to incorporate both slant parallelograms and top and bottom spring-loaded pivots. Finally, they designed the AccuShift levers to accommodate the redesigned SunTour gear train. By the end of 1986, everything was in production. Not a bad year’s work.

Though the new SunTour rear derailleurs look like those of Shimano, they’re not clones. The top spring isn’t as powerful and they shift more like SunTour’s old derailleurs. SunTour designed AccuShift around a more conventional rear derailleur, freewheel, and chain package than Shimano uses. The AccuShift shift lever has built-in overshift so that even late shifts take place before the click. The overshift feature doesn’t work on drops because you can’t push the lever past the click point. AccuShift gear trains are designed to shift early on drops. The revised 1988 AccuShift levers have less overshift than the 1987 models.

SunTour makes three kinds of down tube levers for their AccuShift pack ages: Indexed Power Control (!PC), Index Friction Control (IFC), and Index Control (IC). The IPC lever goes with the Superbe Pro and Sprint gruppos and it includes SunTour’s ratchet friction element. It has three positions: “IJL” (Ultra) for narrow-spaced Winner Ultra-7 freewheels, “RE” (Regular) for wide-spaced 6-speed freewheels, and “P” (Power) for friction shifting.

The IFC levers go with the Cyclone 7000 and Alpha 5000 gruppos. They don’t have the ratchet friction element and they have just two positions, Index and Friction. The IC lever is for economy packages and it doesn’t have a friction position. The IFC and IC levers are designed for wide-spaced freewheels. My Cyclone 7000 upgrade kit included IPC levers; I haven’t tested the IFC or IC levers.

Campagnolo:

Campagnolo is different. There is no Campagnolo Syncro indexed shifting system. There’s just the beautifully engineered Syncro shift levers. Campagnolo leaves the gear train choice up to the buyer. The Syncro lever is designed to work with a wide range of components. It uses a ratchet cam rather than a plate with holes. It has a smooth silky feel and it’s designed to let you feel the shifts as they take place at the rear. On climbs, the click is quite soft, and if the shift hasn’t happened, you move the lever past the click point until you feel the shift. On drops, Syncro feels like a trigger, you push hard and then it snaps to the next position. There’s no feeling your way with drops. The rear derailleur, freewheel, and chain have to shift before the lever reaches the shift point.

Campagnolo plans to supply cams for wide-six, narrow-seven, and SunTour narrow-seven freewheels. So far, only the wide-six cam is available. The three combinations that I tested on the machine shifted just fine. I used a 13-23 wide-six Regina America freewheel, a Regina CX-S chain, and a C-Record or a Victory rear derailleur. The touring combination used a SunTour Winner 13-32 wide-six freewheel, a Regina CX-S chain, and a Campagnolo Victory Leisure rear derailleur. If I were building my own Syncro package, I’d worry a bit about the short cable travel of the wide-six cam, but I haven’t undertaken a test program. Campagnolo has published a list of workable combinations that they’ve tested.

In my opinion, Campagnolo is swimming against the tide. I don’t think that many OEM designers or gear freaks will spend $100 for an elegant set of shift levers to start a do-it-yourself project. Campagnolo’s statement that indexed shifting is for “noncompetitive” cyclists tells it all. Serious (read competitive) cyclists and racers are Campagnolo’s main customers. Campagnolo feels that these serious cyclists will continue to prefer friction shifting. Time will tell.

______ Conventional (Friction) Shift Levers ______

There are good reasons to stick with conventional (friction) shift levers. Probably the best reason for waiting is that indexed shifting is still in the shakedown period and we can expect performance to improve in the next few years. A gear train designed for indexed shifting shifts very sweetly with friction levers, it just doesn’t click.

Almost everyone accepts the shift levers that come as a package with their new front and rear derailleurs. That’s an excellent idea for indexed levers and a good idea for friction levers. However, all friction shift levers have about the same diameter cable drum so you can mix and match derailleurs and friction shift levers, if you have a particular favorite.

_____ Shift Lever Location _____

Friction levers can be installed in four locations: on the stem, on the ends of the handlebars (bar ends), on the handlebars (thumb shifters), or on the down tube. Indexed levers are available in stem-mounted, handlebar, and down tube versions.

Stem-Mounted Shift Levers

Like safety levers and counterweighted pedals, stem-mounted shift levers are a hallmark of gaspipe bicycles. The worst problem is that when you stand up on the pedals honking up a hill, your knee can hit the right lever and kick you out of low gear. Also, the long cable makes shifting a bit vague. If you like the levers up on the handlebars where you can see them, consider a set of indexed mountain bike thumb shifters. If you really like stem-mounted shift levers, there’s just one quality model, SunTour’s PUB- 10 with a ratcheted right-hand lever. Shimano’s SL-S431 and SunTour’s Alpha 5000 provide indexed shifting and short lever arms but they’re designed for the low-end OEM market.

Bar End-Mounted Shift Levers

The tips of the handlebars is my favorite location for shift levers. With half-step plus granny gearing, I often double shift. With bar end levers, I make both shifts with my hands on the handlebars. Loaded tourists and tandems use bar end levers for the same reason. Bar ends make most sense for large riders and large bicycle frames because it’s such a long reach down to down tube levers. I also like the sanitary look of a bicycle with the brake cables and the derailleur cables hidden under the handlebar tape. Bar end levers have two disadvantages. The extra length of cable and casing causes spongy shifts and it’s an extra chore to tape the handlebars,

SunTour’s BarCon ratchet levers are the only ones to buy. At one time, Campagnolo, Huret, Simplex, and Shimano made bar end levers. But the SunTour BarCon shifts so much better than the rest that it’s taken over the market. To date, no one makes indexed bar end levers.

Handlebar-Mounted Shift Levers

Just because you have dropped handlebars doesn’t mean that you can’t use mountain bike thumb shifters mounted in the middle of the handlebars. If you have upright handlebars, thumb shifters are your best choice. They’re available in friction shifting and indexed shifting versions.

Down Tube-Mounted Shift Levers

Levers that mount on the down tube are the choice of all racers and of most serious riders. Top-of-the-line frames come with braze-on mounts for down tube shift levers. The cables are shortest so the shifting is crispest. If you ride a small frame on the drops, it’s just a short reach down to the levers. If you ride a big frame mostly on the tops, you’ll find that it’s a long reach down to the levers. All of the indexed shifting gruppos provide indexed down tube shift levers. Most down tube levers are mounted on the sides of the down tube. Campagnolo and Shimano make down tube levers that mount on the top of the down tube, making it easier to double shift with one hand.

____ Features of Conventional Shift Levers ____

In 1980, I wrote a three-page article about shift levers. I rated 36 different models and expounded on all of the minor differences between them. Since then, another 50 or so shift lever models have been introduced. I’m not going to rate them. Instead, I’ll explain what makes excellent levers better than good levers and I’ll list a few of my favorites that are available in the aftermarket.

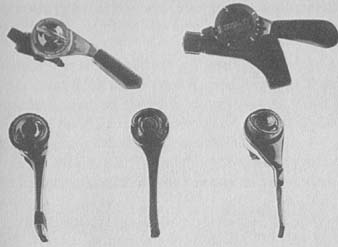

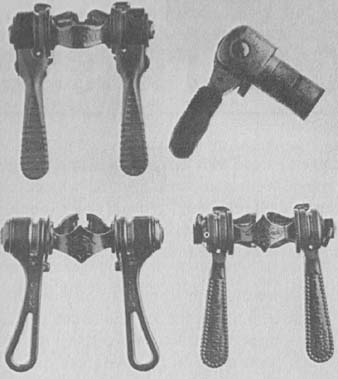

PHOTO 3: Indexed shift levers: top left and right, SunTour XC and Shimano

Deore XT thumb shifters; bottom left to right, SunTour Superbe Pro, Shimano

Dura Ace, and Campy Syncro indexed shift levers.

Lost Motion

On some shift levers, there’s a small amount of lost motion between the friction element and the levers. When you let go of the lever, the cable pulls it back a bit. SunTour deliberately creates lost motion with their AccuShift levers to provide overshift. Some people like a bit of lost motion because it compensates for a late-shifting rear derailleur. I think that lost motion works against precise shifting with friction levers, it’s easy to feel the lost motion, just pull the lever back a bit and see how far it moves forward when you let go.

Friction versus Ratchet

Levers Both front and rear derailleurs have a spring that pulls the cable against the shift lever. The lever pulls the derailleur in one direction and the spring pulls it in the opposite direction. Depending on the rear derailleur, it takes a 25- to 60-pound cable pull to climb. When the derailleur isn’t shifting, the spring still exerts a 15- to 30-pound pull against the cable. You set the friction adjustment of the lever to counteract this pull so that the derailleur doesn’t drop back to the smallest sprocket.

With a friction lever, the friction element works in both directions. With a ratchet lever, the friction element is uncoupled on the climbs. A typical friction lever needs a 12-pound pull to climb and a 1-pound push to drop. A typical ratchet lever needs only a 7-pound pull to climb and the same 1-pound push to drop.

The Simplex Retrofriction down tube shift levers are the racers’ favorite. At the Coors Classic, I noticed several dozen professional racers’ bicycles that were tout Campagnolo except for Simplex Retro-friction levers. The non-index versions of SunTour’s Superbe Pro and Sprint down tube shift levers have ratchets on both levers.

Shift Lever Return Springs

SunTour calls their levers with return springs and ratchets Power Shifters. Shimano’s Light Action derailleurs come with shift levers from the L economy component series, which have a ratchet and a return spring. As in brake lever return springs, to really get all the advantage, the derailleur return spring should have a lower tension.

Front Derailleur Levers

You shift more often on the rear and you have to make finer adjustments of the shift lever. Sometimes the maker provides a fancy, ratcheted, spring-loaded right lever for the rear derailleur, and just a plain, ordinary friction left lever for the front derailleur. With a triple crankset, or with a narrow-cage front derailleur, you do quite a lot of fussing with the left lever. Look for a set of levers with bells and whistles on both sides.

__________ My Favorite Classic Shift Levers __________

After all of the hype on the benefits of indexed shifting, you would expect that all of my bikes would click. Sorry about that. I’ve got Dura-Ace/SIS on the Trek racer and SunTour BarCons on the other bicycles. I have used the 6-speed Dura-Ace/SIS for a year and a half. It’s been pleasant and trouble-free. When I finished the chain tests, I put the 7-speed Dura-Ace/SIS gruppo on the Trek. It’s been just as pleasant and reliable.

I’m scarcely an authority on the over-the-road performance of the various kinds of friction shift levers because I standardized on SunTour BarCon bar end shift levers ten years ago. As the quality of touring front and rear derailleurs has improved year by year, it takes less and less skill to shift precisely, even with mushy bar end levers. Although I’ve got all of the different index packages out in the workshop, I’m still waiting for indexed bar end levers.

PHOTO 4: Conventional shift levers: top left and right, SunTour PUB- 10

ratcheted stem levers and SunTour BarCon bar end shift lever; bottom left

and right, Simplex Retrofriction shift levers and Campy Nuovo Record shift

levers.