A second set of wheels is the best way to give your bicycle a split personality. You can have heavy-duty, soft-riding wheels with nice fat tires for touring, commuting, and wet-weather riding. You can also have lightweight, easy-rolling wheels with narrow, high-performance tires for racing or fast sport touring. You might decide to put a wide-range freewheel on the touring wheels and a narrow- range freewheel on the racing wheels, but that’s optional. Select your second set of wheels to complement your present wheels. If you have narrow racing wheels with high-pressure tires, pick wide touring wheels with lower-pressure tires, or the reverse.

Most likely your present wheels are the in-between sport touring type. If so, pick a second set to match the kind of riding that you do most often. Wheel selection is tied in with tire selection. Therefore, I suggest that you read both this section and section 12 on tires before making a wheel decision.

I’m not a wheel expert, and since I don’t race, I’ve never bothered with tubular tires and rims. I build my own wheels because I enjoy wheel building, but I doubt if I’ve built more than 20 all together. However, I have some very knowledgeable friends who helped me with this section. Jobst Brandt, in his book, The Bicycle Wheel, applied science to the former black art of wheel building. Eric and Jon Hjertberg are the proprietors of Wheelsmith and they’ve made tens of thousands of wheels, albeit many of those Wheelsmith wheels were produced by sophisticated computer-controlled machines. (Interestingly, the machines require more consistent rims and spokes than human wheel builders.) Both Eric and Jobst reviewed this section and made major contributions.

Hubs

A wheel is made of three parts: hubs, rims, and spokes. We’ll look at the separate parts first, then we’ll put them all together and talk about the wheel as a unit.

There are significant differences between different makes of rear hubs, but front hub s are almost all the same. When you select your rear hub, you normally take the front hub that comes with the hubset. You can buy front and rear hubs separately, they’re normally sold as a hubset. There are more than a dozen top-quality brands to choose from in the aftermarket and another 20 or so standard-quality brands in the OEM marketplace. If you restrict yourself to the name brands, there’s surprisingly little performance difference between the best and the worst hubs.

Today’s hubs look very much like the turn-of-the-century models (20 th). Tullio Campagnolo’s invention of the quick-release about 90 years ago was a major innovation. The next major innovation was Shimano’s combining of the hub and freewheel in the Freehub.

You’ll have to decide right up front if you like the idea of combining the freewheel and the hub into a single unit. It has advantages in both hub strength and freewheel versatility. The Maillard Helicomatic and the Mavic MRL freewheel-hub packages are as strong as the Freehub, but their freewheel sprockets use a symmetrical tooth profile and that’s a disadvantage. Also, Maillard and Mavic aren’t nearly as widely distributed as the Shimano Freehub.

I talked about the Freehub’s freewheel features back in section 6, so I won’t repeat that here. If you decide to forget about the combination units and use conventional hubs, you’ve got lots of options and features to reflect upon. I have arranged the following features in rough order of importance.

Over-Locknut Width

The width of the hub is called the “over-locknut width,” which refers to the fact that the measurement is made from outside to outside of the two axle locknuts. Front hubs come in 90mm, 100mm, and 110mm widths. Pick the width that matches the width of your front fork. (Since the hub locknuts fit inside the fork blades, the over-locknut width should be the same as the space between the fork blades.) The 100mm width is far and away the most common for front hubs. There are three fairly standard rear hub widths from which to choose: 120/122mm, 126mm, and 130mm. Pick the rear hub over-locknut width that matches the rear dropout width of your bicycle.

The new ISO standard 5-speed rear hub width is 122mm. Most nominal 120mm hubs are closer to 121mm or. 122mm when you actually measure them.

There was a move to an in-between 124mm width in the early 1980s; narrow-spaced 6-speed, 120mm wheels were a tad weak. Fortunately for standardization, the 124mm width didn’t catch on. If your bicycle measures 124mm, you can still find 124mm rear hubs, or you can take a couple of spacers out of a 126mm hub. However, my advice is to take the easy way out and have your frame spread 2mm wider so that you can use a standard 126mm hub. Some of the latest professional racing bikes are using 130mm hubs, but the mountain bikers are the main users. In fact there’s a trend to 135mm for mountain bikes.

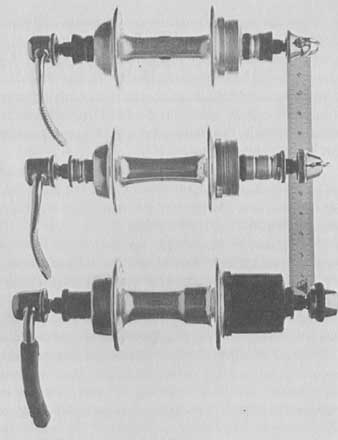

PHOTO 1: Hub over-locknut widths: top to bottom, Campagnolo Nuovo Record

rear hub (122mm), SunTour Superbe Pro rear hub (126mm), and Shimano Deore

XT Freehub (130mm).

The trend is from narrow hubs to wide hubs. The main advantage of wider rear hubs is that they require less rear wheel “dish.” Dishing is the process that centers the wheel rim between the frame dropouts even though the hub flanges are not in the center of the hub. The flanges are moved to the left to make room for the freewheel. To dish a wheel, the left side spokes are inclined inward and have less tension. The right side spokes are more nearly vertical and have more tension. Because of the imbalance in spoke tension, dishing results in weaker wheels. Installing spacers on the left side of the hub reduces dishing and makes the hub wider.

The main disadvantage of wider rear hubs is that the rear axle is more hi stressed. The rear axle is a beam supported by the dropouts. It transmits Ilu load to the wheel through the hub bearings. The right side hub bearing is well inboard of the dropout. The hub width determines the length of the beam. The freewheel width determines the lever arm for the load. The longer the beam and the lever arm, the higher the stress on the rear axle. Rear hubs would In stronger if the bearings were closer to the dropouts. However, wider dropout widths and wider freewheels locate the right side bearing nearer to the center 1 the axle. When the axle breaks, it’s almost always just inside the right cone. The bike store’s usual response is to replace it with a Campagnolo axle and cones. Most mountain bikes use solid rear axles with their 130mm widths.

The Shimano Freehub, the Maillard Helicomatic, and the Mavic MRL take a different approach. They locate the right side hub bearing next to the dropout, where it ought to be. Shimano locates the freewheel bearings inboard of the hub bearing. Maillard uses large-diameter freewheel bearings and locates them in the same plane as the hub bearings.

You might benefit from the history of my Redcay sport tourer. It came as a wide-spaced 15-speed with 120mm dropouts. To maintain my standing in the gear freaks fraternity, I had to have at least 18 speeds, which I wanted to obtain by means of a wide-spaced 6-speed freewheel. First, I tried a 6-speed Shimano freehub, which was available in a 120mm width. The wheel was steeply dished. I didn’t like the looks of it, so I added spacers on the left side to reduce the dish. I had to pull the rear dropouts apart a bit to insert the wheel.

My next two bikes had 126mm dropouts and I wanted to be able to switch wheels between bikes. So I widened the rear dropout width of the Redcay to 126mm. This adjustment, bending the stays, is often called “cold setting.” It isn’t as gruesome as it sounds, especially for bicycles with long chainstays. I put a rear axle between the dropouts and turned the cones outward I/ inch at a time, measuring after each increment. Then I used a “Campagnolo H-tool” to make the dropouts parallel. You might decide to do something similar or have it done by your bike shop.

Basically, 126mm has become the new standard dropout width for wide- spaced 6-speed touring freewheels and narrow-spaced 7-speed racing free- wheels. A 126mm, 5-speed wheel has almost no dish. Table 1 shows the widths that are available for the various hubs.

Sealed Bearings and Bearing Seals

Deep in my heart of hearts, I believe that the bicycle is primarily a means to multiply the distance that you can travel and the load that you can carry. It should remain a simple tool. This principle certainly applies to hub bearings.

--- ---

Table 1: Hubsets (coming soon)

1. The inclusive numbers indicate that spoke holes are available in 4-hole increments.

2. Hubs that are 1% to 1¾ inches in diameter are called small flange. Hubs that are approximately 2% inches in diameter are called high flange. The rare models that fall somewhere in between can thus be called medium flange.

--- ---

Cup-and-cone hub bearings, using nine 1/4 -inch balls in the rear races and ten 3 balls in the front races, have been around since the safety bicycle was invented nearly 100 years ago, long enough to qualify as the standard for hub bearings. In Table 1, where this arrangement is found, it is marked “std.” Only where the bearing count is different from this is it shown.

Cup-and-cone ball bearings are inherently self-adjusting. If they’re properly adjusted, the work lost in bearing friction is trivial compared to the other pedaling losses. They work splendidly in spite of minor misalignment. They have one major disadvantage. They aren’t waterproof. If water or dirt gets in the bearings, the balls and the races will rapidly corrode. You have to clean and regrease your hubs every year or so, more frequently if you ride in the wet.

The hub makers can improve bearing longevity in two ways: by providing a lip seal on the dust cap to keep water out and grease in, or by redesigning the hub to use sealed, cartridge-type ball bearings instead of cup-and-cone bearings. Very roughly, the load capacity of a ball bearing increases directly with the number of balls and with the square of the ball diameter. If everything is designed just right (larger-diameter axle, Conrad-type ball bearings, precise bearing alignment, parallel dropouts, and a bunch of et ceteras that I don’t know about), a hub using cartridge-type ball bearings has about the same capacity as one using cup-and-cone bearings.

Many sealed-bearing hubs advertise that you can replace the bearings yourself. Given the amount of precision required to avoid side loads, I’m not sure that this is such a good idea. In short, I like hubs that use cup-and-cone bearings with a lip seal. (Table 1 shows the type of bearings and seals used in the various hubs.)

__ Number of Spokes ____

There is no 11th commandment that says, “Thou shalt use 36 spokes.” In fact, the classic Raleigh Roadster, which is the model for most of the bicycles in the third world, uses 32 spokes on the front and 40 spokes on the rear. More over, there are hubs and rims drilled for 24, 28, and 48 spokes. However, the vast majority of hubs and rims are drilled for 36 spokes and that’s a good choice for almost everyone. If you pick something other than 36 holes, you’ll often be forced to special order. In the esoteric special-order world, only 28- and 32-hole models are normally carried.

The strength of a wheel depends on the number of spokes, the strength of the spokes, the strength of the rim, and the skill of the wheel builder. Racers use fewer spokes in order to reduce wind resistance. That’s also the reason for disc wheels and flat-bladed spokes. Spoke wind resistance is significant because the top spokes are going twice as fast as the bicycle, and wind resistance goes up the number of spokes. Fewer spokes also weigh less, but there are, if you’re a deadly serious racer, you may find yourself building wheels with fewer than 36 spokes. The less you weigh and the smoother the road and your pedaling style, the fewer spokes you can get away with. Just be aware that racing wheels are generally built to a very high standard and that wheels with 28 or 24 spokes are intended for special applications, not long life.

The loaded tourist has a different problem. A 40- or 48-spoke rear wheel is unquestionably stronger than a 36-spoke wheel. But, if you do crunch a 48- spoke rim, you won’t be able to replace it except at a very large, well-equipped bicycle shop. I use 36 straight-gauge spokes on my loaded touring wheels with good, heavy-duty rims and tires. The main users of 48-spoke rims are tandems. Table 1 shows the numbers of spoke holes available on the various hubs. These are the numbers that are shown in the catalogs. Most stores stock only the 36-hole models. Table 2 is my conservative recommendation on the number of spokes appropriate for various riders and services.

Flange Height

There are two basic hub heights: high-flange and low-flange (a.k.a. large- flange and small-flange). Ten years ago, macho racers used high-flange hubs and wimpy tourists used low-flange hubs; so every bottom-of-the-line, 10-speed racer came with high-flange hubs. The bicycling books told us that high-flange wheels were stiffer and stronger because of the shorter spokes. Low-flange wheels were softer riding.

Recent calculations and tests indicate that these assumptions about strength are just barely true for lateral (sideways) and radial (potholes) loads, but the difference between hub types is very minor. With low-flange hubs, the tangential (pedaling) load stresses the rear spokes about twice as much. How ever, the pedaling load is a small part of the total spoke tension and low-flange hubs are more than strong enough. The main reason to use low-flange hubs is because they’re lighter. Most professional racers now use low-flange hubs. However, if you are going to use more than 36 spokes in a wheel, you should use a high-flange hub to provide enough metal between the spoke holes.

Some hubs slant the flanges inward so that the outer spokes don’t have to bend as much. Phil Wood and SunTour advertise this feature. (Table 1 shows the flange heights available for the various hubs.)

There are no standard hub diameters. This becomes a nuisance when you buy spokes. You have to know which hub and which rim you will be using, and how many spoke crosses. Then you can look up the appropriate spoke length. If your front and rear hubs are the same diameter, then you can use the same size spokes on both.

TABLE 2. Recommended Number of Spokes (coming soon)

____ Threads ____

There are four threads available for the rear hub—freewheel thread: ISO, English, Italian, and French. However, you almost have to special order a hub to get anything other than ISO or English (1.37 X 24 tpi). There’s no reason to do this unless you have a collection of bastard-threaded freewheels or you’re a masochist.

There are still four threads in use for axles. However, there’s a trend to the standard ISO thread. That’s what you’ll find in most replacement hubsets except Campagnolo. The ISO (9mm X 1mm pitch) thread for the hollow front axles is the same as the old French thread. The ISO (10mm X 1mm pitch) thread for the hollow rear axle will mate with most of the older English and French axle threads. You don’t have to worry too much about axle thread standardization because it isn’t a great expense to replace an axle along with its cones and locknuts. Table 1 shows the type of thread listed in the manufacturer’s catalog.

___ Quick-Release ___

Your replacement hubs will almost certainly come with hollow axles and quick-release skewers. There’s a modest case to be made for solid axles with nuts. They’re quite a bit stronger, a bit lighter, and they make it harder to steal the wheels from a parked and locked bicycle. For most people, however, the convenience of a quick-release is worth these disadvantages. The trial lawyers who take cases on contingency are all in favor of quick-releases. At any given time, there are a dozen or so lawsuits involving dumbhead cyclists who failed to tighten the quick-release on their front wheels. Table 1 shows which hubset models are available with a fastening system other than the quick-release.

Weight

The old rule that a pound off the wheels equals two pounds off the frame is really talking about the weight of the rims and the tires. They are on the outside the flywheel and they contribute to the rotational inertia of the wheel. That’s icy engineering talk to say that heavy tires and rims accelerate slowly. The hub doesn’t contribute very much to the rotational inertia so that it’s weight Ii more like frame or component weight. The lightest hubs have low flanges, and nuts in place of quick-releases. The sealed-bearing hubs that use large-diameter, hollow axles and built-up bodies are quite light. Finally, it should be noted that the weight of a Shimano Freehub compares very well with the combined weight of a conventional hub and freewheel.

Table 1 shows the weight of a low-flange hubset with quick-release. The rear hub is 126mm. The weight for the two Shimano Freehub models includes the freewheel body but no sprockets. Subtract about 175 grams to make the weight comparable to conventional hubsets.

__ Hubset Makers __

The trend is toward including hubs in the gruppo. However, the small hub makers are surviving because so many bicycles have more than one pair of wheels.

Campagnolo-- Campagnolo’s hubsets set the standards for conventional cup- and-cone designs. Only the two top lines, C-Record and Nuovo Record, are widely available in the replacement market. The C-Record has a fancy new dust cover that requires a special remover. Campagnolo uses nine 7/32-inch balls instead of ten 3/16-inch balls in their Nuovo Record front hubs. C-Record uses nine 3/16-inch balls. Campagnolo measures the balls to a micron and installs matched sets. If you wear out the cups on a Campagnolo hub, you can press them out and replace them. A good pro bike shop will carry replacement Campagnolo cups.

Maillard -- Maillard makes three lines of hubs: Maillard, Normandy, and Atom. Their conventional hubs are available with cup-and-cone bearings with seals or with sealed cartridge bearings. In the old days, Normandy was high- flange and Atom was low-flange. Now, Normandy is the middle line and Atom is the low-priced line. Trek and Peugeot bicycles often use Maillard hubs, so their dealers tend to carry Maillard. Otherwise, distribution is very sparse. The Helicomatic design is available in all three lines. The Helicomatic hub is as strong or stronger than the Shimano Freehub, but the

Mavic -- Mavic hubs are racing favorites. They use sealed cartridge ball bearings with large-diameter, hollow aluminum axles. The bearings are user- replaceable, but it takes special tools. The 7-speed Mavic MRL freewheel-hub was introduced in 1987. All of the sprockets are narrow-spaced and they use the identical coarse thread. Sprockets from 12 to 28 teeth are available.

Phil Wood --Phil Wood is the father of the sealed-bearing hub. He has done more to popularize the use of sealed-bearing hubsets than anyone. His quality control includes individual inspection of every cartridge bearing. When your Phil Wood hub finally needs service after many thousands of miles, you send it back to the factory. If you believe what Phil says about the care and feeding of cartridge ball bearings, then you won’t buy hubsets with user-replaceable, sealed bearings. The Phil hub uses a big hollow axle. It isn’t particularly hand some, compared to most of the competition, but it’s stronger than all get out.

Shimano --Shimano makes conventional hubs in eight or nine price levels for the OEM market. Dura-Ace, Sante, 600 Ultegra, 105, and Deore XT are the hubs that you’ll find in the replacement market. All versions come in either Freehub or conventional versions. Shimano hubs have cup-and-cone bearings with an effective lip seal. There is a little hole in the dustcap that allows you to inject a dollop of grease without taking everything apart.

Freehubs used to be available at six different price levels. Then Shimano only imported Dura-Ace and Deore XT Freehubs. In 1988, they started to import the whole range of Freehubs. I’ve already raved about the Freehub in section 6 on freewheels. It’s the most versatile freewheel available and it comes with one of the strongest hubs.

Specialized --Specialized hubsets are made in Japan to their specifications. They have user-replaceable, sealed cartridge bearings. The Specialized 126mm hub is available as a 5-speed and the 130mm hub is available as a 6-speed. With the extra spacers on the left side, these allow you to build almost dishless wheels.

SunTour -- SunTour hubs come in four versions: Superbe Pro, Sprint, Cyclone 7000, and Cyclone. The Cyclone 7000 has cup-and-cone bearings. The remainder have user-replaceable, sealed cartridge bearings. SunTour and Specialized hubs are very similar. They’re both made by Sanshin.

Everybody Else -- Edco, Excell-Rino, Galli, Gipiemme, Miche, Otmega, Omas, and Zeus all make Campagnolo-like hubs for the European racing market. American Classic, Durham (Bullseye), and Hi-E Engineering are American makers of sealed-bearing hubs. Aral, Sakae Ringyo, Sanshin, and Suzue are major Japanese suppliers to the OEM market. These 15 companies make very good hubs but you won’t often see them in the aftermarket.

___ Rims ___

The rim business is a jungle. Most of the major gruppo makers don’t bother with rims, so the small companies have survived. I found 20 different rim makers in my review of the catalogs and each company makes ten or more different models in a wide range of sizes. I picked the dozen companies that have the widest distribution.

There are two main considerations in rim selection: size and weight. The rim should match the tires that you plan to use and the rim should be heavy enough (or light enough) for your proposed use. Let’s look at these important considerations first and then get into the less important items.

___ Rim Selection: Matching Rims with Tires ___

Rim selection and tire selection go hand in hand. Your rim selection limits your tire selection. Your first decision is tubular tires and rims versus clincher tires and rims. If you have a deep inner craving for tubular tires, it might be a good idea at this point for you to read what I have to say about tubulars in section 12. After that, if you’re still convinced that tubulars are a good idea, you’ll find a section on tubular rims further on. Table 3 has four columns covering tire-rim compatibility: inside width, edge type, service, and tire compatibility.

__ Rim Width __

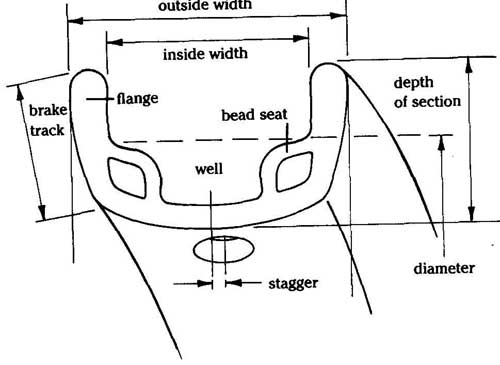

Assuming that you opt for the flag, motherhood, and clinchers, you then have to make a basic narrow tire versus wide tire decision. There are five sizes of tires and three sizes of rims. Tire size labeling is a mess and it’s covered in detail in section 12. First, decide on the range of tire sizes that you plan to use, then select rims to match. The key rim dimension is the inside width between the rim flanges. The outside width is tied into the inside width so it’s not important by itself. Rims that have an inside width of 13mm or 14mm (a bit more than ½ inch) are designed for narrow tires. Rims with an inside width of 15mm or 16mm are designed for medium-width tires. Rims with an inside width of 16.5mm or more are designed for wide touring tires. (The basic parts and dimensions of a rim are shown in FIG. 1.)

TABLE 3. Clincher Rims (coming soon)

FIG. 1 Clincher rim nomenclature.

__ Rim Edge Type __

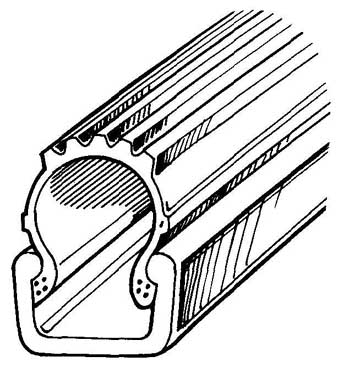

The second important feature of clincher rims is the shape of the rim flange. There are three types: straight-side, hooked-edge, and an intermediate type with a vestigial hook that I call “bulged.” Straight-side rims have bead seats and dropped centers. The bead seat mates with the bead of a wired-on tire to keep it on the rim. The dropped center makes it possible to mount the tire. A hooked-edge rim is designed to mate with a hook-bead tire. In 700C and 27-inch sizes, hooked-edge rims are hybrids. They have both hooked edges and bead seats. Sometimes the dropped center is just a concave inner bed, but there’s still a bead seat that centers the tire. In the smaller diameters, there are “pure” hooked-edge rims that don’t have bead seats and they rely entirely on the hooked-edge to center and retain the tire. (See FIG. 2 for a depiction of a pure hooked-edge rim.)

If you plan to use narrow, high-performance, skinwall tires and to inflate them to maximum pressure, you need a hooked-edge rim. Rigida calls this a “crotchet” edge. Foldable tires use Kevlar beads, and hooked-edge rims are mandatory. If you install cheap gumwall tires on hooked-edge rims, the tire sidewall may fail just above the bead because the hook has such a sharp radius. Usually the tire wears out before this happens. Finally, straight-side rims give a poorer ride because the part of the tire’s sidewall that’s inside the rim can’t soak up road shocks.

For any given tire width, construction, and inflation pressure, tubular rims and tires perform best. Hooked-edge rims and tires are next and straight-side rims and tires are worst. There’s no good reason to buy straight-side rims today. You can get hooked-edge rims in all three widths and they’re inherently superior to straight-side rims.

_ Tire Compatibility _

Table 3 shows tire compatibility. Based on ETRTO (European Tire and Rim Technical Organization) recommendations, I took the rim inside width and multiplied by 1.45 to get the smallest tire size and by 2.0 to get the largest tire size. ETRTO suggests that hooked-edge rims can retain tires up to 2.25 times the rim inside width. The tire sizes shown in this column are the actual ETRTO section widths, not the labeled tire sizes.

_ Rim Weight _

It’s more fun to pedal a bicycle with light wheels. It accelerates faster and it feels alive beneath you. Light wheels and tires don’t cost that much extra, If it weren’t for flat tires and bent wheels, we’d all be riding on ultra-light wheels. The rim, tire, and tube are located at the outside of the wheel diameter. They’re the important elements in tire weight. The basic problem is building a pair of light wheels that are exactly light enough for your particular combination of rider weight, road roughness, and riding style.

FIG. 2 A hook-bead tire mounted on a hooked-edge rim.

Jeff Davis of Campagnolo shared his formula with me. Multiply your weight in pounds by 1.75 to get the absolutely lightest tubular rim weight in grams that you can use on a smooth surface for a few races. Multiply your weight by 2.75 to get the weight of the lightest rim that you can use in normal service on normal roads. There’s probably no substitute for trial and error. Build a pair of wheels that are too light and when they fall apart, build another pair using rims that are just a tad heavier and stronger. If you go this route, you’ll have lots of flats and you may crunch one or two rear wheels before you find your personal limits. Lightweight wheels are a bit addictive. It’s always tempting to go too far.

I have an analogy. In my wild youth, I used to race boats powered by souped-up, flathead, Ford V-8 engines. The engines were built to class rules so most of the top boats had the same power. We burned a mixture of alcohol and nitro-methane. Nitro-methane releases oxygen as it burns so it acts like a liquid supercharger. It also releases a lot of heat and too much heat burns holes in the pistons. There wasn’t any magic formula to tell us when to stop. In the last heat of a close championship race, there were lots of blown engines. Light tires and light rims with a minimum number of spokes are like nitromethane.

Lightweight clincher rims are made from thin-walled aluminum extrusions. (Tubular rims are often made from an aluminum alloy strip.) Extruding is a process that squeezes the metal through a die under very high pressure, like toothpaste from a tube. It’s hard to extrude uniform thin-wall cross sections. That’s why lightweight rims cost so much. As the die wears, the walls become a bit thicker. A rim extruded from a worn die will weigh more than one from a new die. It will also be stronger. The makers don’t deliberately lie about rim weight but they weigh rims made with new dies.

There’s a significant sample-to-sample variation in rim weight. Table 3 shows two weights for several rim models. The first is the maker’s advertised weight. The second (in parentheses) is the weight of a typical run-of-the-mill rim. The weight is for a 700C rim. A 27-inch rim weighs a bit more.

Wide rims take more metal, so they naturally weigh more than narrow rims. I don’t worry about the weight of my heavy-duty touring wheels. When I want to go fast, I use the bike with light wheels.

___ Rim Cross Section ___

Much of a wheel’s strength comes from tight spokes. The rim distributes the shock loads to the spokes and loose spokes impose a severe stress on the rim. Some rim cross sections are more efficient than others. Two rims may weigh the same, but the one with the more efficient cross section will do a better job of resisting radial deflection from potholes and lateral deflection from skidding in a corner. Deep cross sections are stronger radially. Wide cross sections are stronger laterally. In clincher rims, complex box-type cross sections with thin walls are more efficient than simple cross sections with thick walls. Unfortunately, hollow cross sections are harder to extrude, so light, strong, efficient clincher rims cost more than their simpler cousins.

The clincher rim with a cross section like a box is the most efficient. It copies the tubular box cross section. The next most efficient is the aerodynamic cross section, which is stronger against radial loads because it’s deeper. Next comes the Super Champion Model 58, then the Weinmann Concave cross section. The least efficient cross section is the wide, straight-side rim that’s used in standard-quality bicycles. Rim dimensions and cross section types are shown in tables 3 and 4.

__ Rim Material __

Steel rims have no place on a bicycle that’s ridden for fun. For any given weight, a steel rim is weaker than an aluminum rim. A steel rim is also more J. likely to dent if you hit a pothole. Moreover, chrome-plated steel rims stop very poorly when wet.

Until about five years ago, most alloy rims were made from a 3000 series aluminum alloy that uses about 1 percent of manganese and magnesium. This alloy attains its strength by cold working in the extruding and forming processes. Sometimes these rims are annealed after cold working to increase their ductility and fatigue resistance. Sometimes the advertisers call the annealing process “heat treating.” That’s misleading since the rim actually loses strength in the annealing process.

Recently, there’s been a move to make rims out of aluminum alloys that can be made harder and stronger by heat treating. Matrix, Mistral, and some Rigida rims use a 6000 series aluminum alloy that employs silicon and magnesium as the alloying elements. Campagnolo rims use 7000 series aluminum alloy, which employs zinc. After heat treating, rims made from 6000 or 7000 series alloys are stronger and/or more ductile than rims made from 3000 series alloy. They can legitimately be called “heat-treated.” Tables 3 and 4 indicate the particular aluminum alloy used in each rim model.

_ Surface Finish _

The surface of an alloy rim can be left in its natural polished condition or it can be anodized. An anodized rim is placed in a hot conducting bath and a current is passed through it. This forms a protective aluminum oxide layer on the surface. “Soft” anodizing makes the rims prettier and reduces corrosion and pitting. Dyes in the solution can add color. “Hard” anodizing is a longer, more expensive process. The current density is higher and the solution is chilled. This results in a much thicker oxide layer. A hard-anodized rim is somewhat stronger than a soft-anodized rim and the thick oxide layer reduces wear on the brake track. Hard-anodized rims also cost more. A hard-anodized rim is dark gray, but not all dark gray rims are hard anodized.

Some inexpensive steel rims have serrations or dimples on the brake track. This doesn’t help wet-weather stopping. It makes it worse. Tables 3 and 4 show the various surface finishes that are listed in the makers’ catalogs. Some times a different surface finish has a different model name. I don’t show all of the different models, just the top-quality one. Where more than one symbol is shown, it means that the rim is available with different finishes.

TABLE 4. Tubular Rims--Make and Model. The inclusive numbers indicate that rims are available in 4-hole increments.

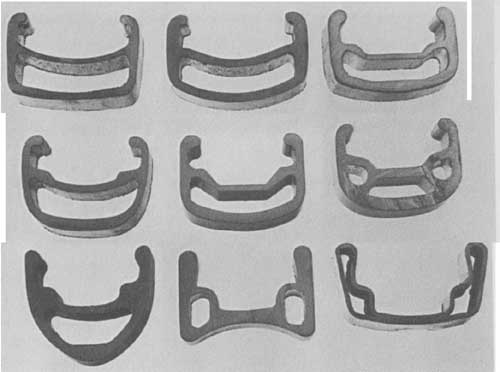

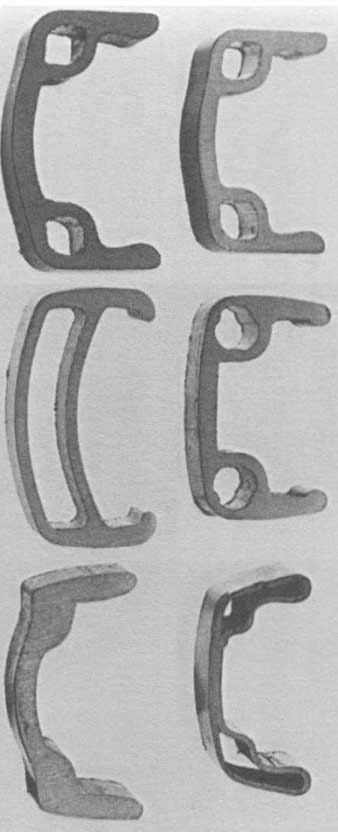

PHOTO 2: Cross sections of narrow clincher rims (widths in parentheses):

top left to right, Mavic MA-2 or MA-40 (13.5mm), Mavic Module C or Module

3-CD (15mm), and Wolber Super Champion Gentleman (14mm); center left to right,

Rigida AL 1320 (13mm), Mistral M 13L (12.5mm), and Mistral M 13 (13mm); bottom

left to right, Mistral Aero M 14A (14mm), Weinmann Concave A-124 (14mm),

and an economy steel rim (14mm).

_ Rim Diameter _

There are two main choices for rim diameter, 27-inch and 700C. The difference between them is found neither in the actual outside or inside rim diameter. The difference lies in the “bead seat diameter” where the bead of the tire rides on a ledge in the rim: 700C rims have a 622mm bead seat diameter, while 27-inch rims have a 630mm bead seat diameter. Size 700C wheels can be interchanged with tubular wheels without moving the brake pads. However, tire availability is the main factor to consider when making the choice. (I’ll have more to say about this in section 12.) Brake reach and fender clearance are other factors to consider. All good-quality clincher rims are available in both 27-inch and 700C diameters, so I don’t show this in Table 3.

__ Number of Spoke Holes __

I discussed the reasons for using more or less than 36 spokes earlier when talking about hubs, so I won’t repeat them all here. But I will point out that reducing the rim weight and the number of spokes works at cross purposes. A 24-spoke rim needs more weight to spread the higher spoke forces ban does a 36-spoke rim. You have to compromise either weight or wind resistance.

Tables 3 and 4 show the number of spoke holes listed in the rim makers’ catalogs. Rim availability is a different story. You can find narrow, lightweight, racing rims with 28, 32, and 36 holes. You can find wide, tandem, or loaded touring rims with 36, 40, and 48 holes. Everything else is special order and wait. Good-quality rims stagger the spoke holes. This lets the spoke leave the rim tangentially and it anchors the rim to resist torsional deflection.

Spoke Eyelets

Good-quality rims have spoke eyelets to distribute the spoke force over a wider area and to reduce friction of the spoke nipple when you true a wheel. Eyelets are essential for lightweight rims. Box-section rims have a choice be tween single eyelets on the bottom of the box or sockets (double eyelets) that extend through to the top of the box and tie the rim together. Sockets are better and they always cost more. Tables 3 and 4 indicate the type of eyelets found on different rims.

PHOTO 3 Cross sections of medium and wide clincher rims (widths in parentheses):

top left to right, Mistral M 17 (18mm), Wolber Super Champion Model 58 (17mm),

and an economy steel rim (16mm); bottom left to right, Mistral M 20 bulged-edge

(20mm), Mavic Module 4 hooked-edge (19mm), and Araya 16A(1) straight-side

(19mm).

_ Joint Type _

The joint is a critical part of the rim. If the joint bulges at all, it will cause the brakes to grab. If the rim isn’t completely round at the joint, the wheel won’t be completely true. When you buy rims at a bike store, pick the ones that have the smoothest joints. Most rims are rolled into a circle and then joined with either pins in the holes or sleeves. Mistral uses an epoxy glue to hold the pins. Everyone else relies on a press fit. There’s no problem with the joint separating because the compressive force of the spokes pulls the joint together. A few of the heavier rims have flash-welded joints that are ground smooth after the welding. This gives a stronger, more uniform joint provided the grinding is properly done. Wheelsmith inspects thousands of rims and rejects the ones with poor joints. The level of joint uniformity is shown in tables 3 and 4. The tables also show the type of joint.

__ Valve Hole __

Picking the best type of valve hole is easy. Buy Presta valve tubes and use Presta valve rims. The Presta valve hole is smaller than the Schrader valve hole and it weakens the rim less. Besides, tubes with Presta valves are easier to inflate.

__ Service __

I made a judgment in Table 3 about the normal kind of riding for each rim: whether it is racing, sport touring, or loaded touring. I don’t think that clincher rims are suitable at all for time trials, where speed is the dominant consideration.

__ Tubular Rims __

The tubular rim’s box cross section has a higher strength-to-weight ratio than any clincher rim cross section. Tubular rims can be welded from aluminum alloy strips, rather than extruded. A tubular rim doesn’t have to keep the tire from expanding under inflation pressure. For these reasons, a tubular rim will always weigh less than a clincher rim of the same strength. The rim makers make a range of weights. The lighter rims have thinner walls. It’s as simple as that. Many users have the idea that their favorite lightweight rim is somehow stronger than Brand X’s middle-weight model because of heat treating, hard anodizing, better joints, or just plain virtue. Maybe so, but the strength differences are less critical than weight.

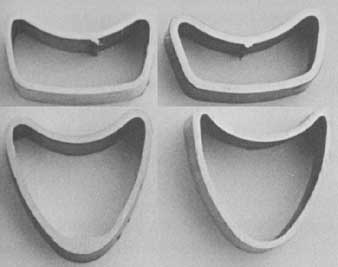

PHOTO 4 Cross sections of tubular rims: top left and right, Fiamme Ergal

(lightweight) and Fiamme Silver (team weight); bottom left and right, Mistral

M 19A Aero dynamic and Araya Aero 1 (washers required).

Wheelsmith co-owner Eric Hjertberg divides tubular rims into three classes:

- • Extra-light, 280 to 320 grams, for limited use in time trials and for riders under 130 pounds.

- • Lightweight, 320 to 380 grams, for smooth roads, criteriums, and track racing.

- • Team weight, 380 to 460 grams, for general road racing and training.

Selecting tubular rims is fairly straightforward. They almost all use the same box cross section. The main differences are in weight, joint quality, and in the aluminum alloy and its heat treatment. Light, thin-walled rims are harder to make so they’re more expensive. They’re also significantly weaker, Heat- treated or hard-anodized rims are somewhat stronger and a lot more expensive. The new aerodynamic shapes are the exception. They’re heavier than box- shaped rims of the same strength. You gain in wind resistance and lose in weight.

The best-quality tubular rims have spoke sockets that extend through the box cross section to join the box together. Aero rims don’t use eyelets; you often have to use washers on the nipples, which is a bother. Advertised rim weights and actual rim weights differ. If you’re really on a lightweight kick, you should weigh your rims before you buy them. When you talk to the vendors, they all tell you that their competitors understate their weights.

_ Rim Makers _

The gruppo companies have not been interested in rims, so there’s still lots of competition.

Ambrosio -- Ambrosio is an Italian company that’s best known for tubular rims. Durex is their buzzword for hard anodizing.

Araya -- Araya is a member of JBM (Japan Bicycle Manufacturers), the Japanese combine that includes Shimano. They’re a major supplier of OEM clincher rims.

Assos -- Assos is a Swiss company that makes very expensive, light, high- quality, aerodynamic tubular rims.

Campagnolo -- Campagnolo entered the rim market in 1985 with three lines: Victory, Triomphe, and Record. In 1987, they expanded to five lines and named them Sigma, Delta, Omega, Epsilon, and Lambda. In the process, the advertised weights of the lightest rims became heavier. Campagnolo makes their top- quality Sigma rim from Ergal, a heat-treated aluminum zinc alloy.

Fiamme and Rigida -- Fiamme and Rigida are two small French rim companies. You’ll find their tubular rims in the aftermarket but the clincher rims are largely made for the OEMs.

Matrix and Mistral -- If you believe in buying American, these are your rims. Trek makes Matrix in Wisconsin and Sun Metal makes Mistral in Indiana. They both make only top-of-the-line, hard-anodized rims from heat-treated 6000 series alloy. I wish they would provide spoke sockets with their box-section rims. I made the wheels for my Trek 2000 with Matrix Titan rims. They held up well to the abuse I gave them when I was testing ultra-light clincher tires.

Mavic -- Mavic is the premier French rim maker. Mavic’s Module E rim and Michelin’s 27 X 1 Elan tire were the first narrow clincher package back in 1975. The Mavic 0-40 was the best selling high-performance clincher rim until 1986, when it was replaced with the MA-40. Wheel builders often prefer Mavic be cause their rims are true and have uniform joints. The Mavic cross section has an almost flat floor. This means that there isn’t a well for the tire bead when you’re mounting a tire. I found it harder to mount Japanese Kevlar-beaded tires on Mavic rims than on rims with a deeper well.

Specialized -- Specialized introduced the Saturae line of imported rims in 1984. The clinchers came from Japan and the tubulars from Italy. In 1987, Specialized appeared to be de-emphasizing rims.

Weinmann -- Weinmann makes a full line of steel and alloy rims for the OEM market. You find the Weinmann A-124 and A-129 Concave rims in the aftermarket. These rims have a unique cross section. If you were going to pedal your bike for 20 miles on bare rims, they would be your choice. I’ve used half a dozen Weinmann A-124 rims. They’ve held up well, but they lack a hooked edge so I can’t use them with foldable tires.

Wolber -- Wolber was an Italian tire company that bought the Super Champion rim company a few years back. The wide Super Champion Model 58 is my favorite touring rim. In 1987, they introduced the heat-treated, hard-anodized Model 59 that has a welded rather than pinned joint. In like fashion, the 430 is an upgrade of their GTA Gentleman narrow clincher rim.

Spokes

After all of the complication of hubs and rims, it’s a pleasure to write about spokes. Spokes are the highest-stressed components on your bicycle and when they were built to normal manufacturing tolerances, spoke failures were quite common. Life has become simpler in the last few years because the design of today’s top-quality spokes has become quite refined. There are now only two widely distributed brands of top-quality spokes: DT and Wheelsmith.

Today, stainless steel is the only spoke material for serious cyclists. Also, there are only four diameters to concern you: the straight and bulled versions of 14 and 15 gauge. The old bicycle books contain a lot of out-of-date information about problems with stainless steel spokes from old spoke companies like Stella and Robergel. The problems just don’t happen with today’s top-quality spokes.

__Spoke Companies__

The pressure for better spokes began when companies like Wheelsmith and Performance Bicycle Shop set up computer-controlled wheel-building machines to make top-quality wheels. They found that without absolutely uniform spoke lengths and threads, the machines required excessive adjustments and the wheels needed more final trueing. The Swiss spoke company Drahtwerke Trefilerie (DT) became known for high uniformity at the same time that Robergel, the old favorite spoke company, was encountering quality control problems. After building 25,000 wheels with DT spokes, Wheelsmith went to Japan to have their own top-quality spokes made to even more rigorous specifications. Wheelsmith and DT spokes are widely available. Alpina and Berg Union also make top-quality stainless steel spokes, but they sell largely to the OEM market.

__ Spoke Material __

Spokes are made from carbon steel or stainless steel. Carbon steel spokes can be chrome-, nickel-, cadmium-, or zinc-plated (galvanized), but none of them lasts very long. Chrome-plating gives a brilliant luster but poor rust protection, and chrome-plated spokes that are improperly heat-treated become brittle. In short, chrome-plated spokes are best for show bikes. Galvanized spokes look crummy on any bike. They rapidly discolor in coastal climates. If you try to true a wheel after a year’s service, you may find that your chrome- plated or galvanized spokes are welded to the nipples with corrosion. Low-cost galvanized or chrome-plated spokes are a hallmark of standard-quality bicycles.

The wire used to make spokes is repeatedly cold drawn to develop a very high tensile strength and fatigue resistance. Typical ultimate strengths are in the 150,000 psi (pounds per square inch) range. The old folklore said that carbon steel spokes were stronger than stainless steel spokes for any given size. The tensile strength data that I’ve seen doesn’t support that conclusion. Rather, it suggests that some of the old spoke companies had difficulty making consistently high-strength stainless steel spokes. Today, if you want stronger spokes, use a larger gauge.

__ Spoke Diameter __

The gauge numbers for wire and spokes read backwards. Small gauge numbers are thicker. I remember this by thinking that 16 gauge is about .46 inch thick and 8 gauge is about ¼ inch thick. There are only two spoke gauges in common use: 14 and 15. Fourteen-gauge spokes are 2mm in diameter. Fifteen-gauge spokes are 1.8mm in diameter.

Spokes come in butted or straight gauge. Butted (or double-butted) spokes are thicker at the highly stressed ends, and thinner in the main body. Wheelsmith reduces the diameter of the butted section more than DT. Wheelsmith spokes are 14-16-14 gauge and 15-17-15 gauge. DT spokes are 14- 15-14 gauge and 15-16-15 gauge. Butted spokes cost half again as much as straight-gauge spokes. Ten years ago, every top-quality wheel was built with butted spokes. Today, there’s a trend to straight-gauge spokes, especially for loaded and sport touring wheels.

I like butted spokes because I think that their fatigue life is improved by the reduction of stress at the threads and at the elbow. (Spokes fail from fatigue rather than from overload.) However, it’s certainly easier to build a wheel with r straight-gauge spokes because they don’t twist as much. Wheel-building machines have problems with the twisting of butted spokes.

The weight difference between 36 straight 14-gauge spokes (the heaviest) and 36 butted 15-17-15 gauge spokes (the lightest) is about 3 ounces or 110 grams. If you want very light wheels, it makes more sense to use fewer spokes rather than thinner spokes. That way you also reduce wind resistance. If you break a 14-gauge spoke, the wheel will remain truer, and you can probably open the brake and ride home. Fifteen-gauge straight or butted spokes are for light riders. For average riders with 36-spoke wheels, I suggest straight 14-gauge spokes for your touring wheels and 14-gauge butted spokes for your light racing wheels.

__Nipples__

Nipples are usually made of fickle-plated brass. Aluminum nipples are available, sometimes anodized in pretty colors. The 1-ounce saving per wheel isn’t worth the hassle of dealing with the softer material. Extra-long nipples are available for certain extra-thick rims.

The ISO standard thread is 56 tpi and most spokes now use that standard. In theory, you can swap nipples of the same gauge. However, if you do, your wheels will shout, “amateur buildert” Use the nipples supplied by the spoke maker. The typical quality spoke has about ¼ inch of threads or 22 threads. The typical nipple has a counterbored lead-in hole and about 16 threads. Wheelsmith nipples have a shallower hole and a few more threads, which gives a bit more tolerance in selecting spoke length.

__Spoke Length__

The perfect wheel has all of the spoke threads inside the nipple and no spoke end projecting beyond the nipple. It really isn’t all that critical, but it looks prettier. Determining the exact spoke length for each combination of hub diameter, rim diameter, number of crosses, and rear wheel dish is lots of fun. I usually build one wheel that’s a bit off and get it exactly right the second time. Sutherland’s Handbook for Bicycle Mechanics (4th ed.) takes 26 pages to list all of the combinations. Wheelsmith sells a rim caliper and a hand-held computer to precisely calculate spoke length. Spokes come in 1mm steps in the most common lengths.

__ Flat Spokes __

Flat or aerodynamic spokes are for wind resistance fanatics. There are three kinds. One kind has a double bend instead of a head. These can be wiggled head first through the spoke holes in the hub. The second kind has a conventional head and you have to slot the spoke holes in the hubs to allow the flat blade to be inserted. The slotting weakens the highly stressed hub flange (and voids the warranty). The third kind has an aero profile that can be pushed through the hub. Aerodynamic spokes are exotic items, and I have the feeling that the experts specifying wheels and spokes for Olympic record bikes may not need to read this book.

Wheels

Now that you know all about hubs, rims, and spokes, there’s not a whole lot more involved in selecting your new wheels. Spend about the same amount on rims as you spend on hubs. Decide your spoking pattern and your source of supply and you’re ready. Wheel building is still part art, part science, and part black magic. Two good books— The Bicycle Wheel by Jobst Brandt and The Spoking Word by Leonard Goldberg—and an article by Dan Price and Arthur Akers in the June 1985 issue of Bike Tech have done much to increase the science and decrease the black magic.

_ Sources of Supply_

You have four choices as to how you acquire your new set of wheels.

• Buy all of the parts and build the wheels yourself.

• Buy hand-built wheels from the local wheel builder with the best reputation.

• Buy ready-made wheels such as those sold by Wheelsmith.

• Buy internet/mail-order wheels.

I think that serious cyclists should build their own wheels. It’s one of those satisfying human achievements that rarely happens in our complex technological world. If you can build an adequate wheel, you can also true your old wheels. Home wheel building has been made much easier by Eric Hjertberg’s series of four articles in the January, February, March, and April 1986 issues of Bicycling. Eric wrote essentially the same instructions in Bicycling Magazine’s Complete Guide to Bicycle Maintenance and Repair. I sat in my workshop with the February and March articles in my lap and laced up my best ever pair of wheels. A year later they’re still true. The only hard part was knowing where to stop as I added more tension to the spokes. John Allen, who is also a musician, says to pluck the spokes and stop at G# or A above middle C. If you feel a bit nervous about the spoke tension in you home-built wheels, get an impartial evaluation from a wheel builder.

If you’re not really into the arts and crafts thing, then try to buy your wheels from your local pro bicycle store. Every community has its own builders of “Stradivarius” wheels with super-tight spokes and perfect trueness. Ask five bike nuts and you’ll get six different names. Most bicycle shops have one mechanic who is the acknowledged shop champion. These people build better (maybe only a bit better) wheels than you or I, because they’ve built so many. Custom-built wheels are surprisingly inexpensive. You pay a whole lot more to get your VCR fixed and it might not be fixed right. Just remember that it takes about three hours to build a top-notch set of wheels, so be prepared to pay Stradivarius a fair price for his fiddle.

Wheelsmith’s ready-made wheels are a small step down from their hand- built super wheels. I visited the factory and I was impressed. Every wheel is checked for trueness and uniform spoke tension by a builder at the end of the line. If it takes more than a minor tweak, he (he was a she the day I was there) goes over and adjusts the machine. Many busy bike stores sell Wheelsmith wheels because their mechanics are too busy to hand build every wheel. The machines take a lot of work to set up so they require a long run of identical wheels. The machines also demand spoke and rim uniformity and as a result Wheelsmith has a tremendous background on spoke and rim quality control. If you order an oddball, extra-light, 24-spoke, radial wheel, the Wheelsmith bike shop will make it by hand.

I feel more nervous about mail-order wheels than I do about mail-order clothes or components. I’m willing to accept that some of the mail-order houses may have very talented builders, but I worry about what the gorillas at UPS or Federal Express do to those big, fragile wheel boxes. Also, if the wheel goes out of true after a few rides, you don’t have the convenience of having its builder nearby to re-true it for you.

There’s a type of OEM machine-made wheel that you shouldn’t touch with a 306cm pole. I’m referring to the low-cost replacement wheel with steel rims and chrome-plated spokes. Buying cheap wheels of this type is definitely not the way to upgrade your bike.

__Spoking Patterns _

As part of the study reported in Bike Tech, Price and Akers built radial, one-, two-, three-, and four-cross wheels and tested them for torsional, lateral, and radial strength.

There really weren’t any startling conclusions. We all knew that the more crosses, the stronger the wheel is torsionally. The torsional load from pedaling is only a small part of the spoke tension. The difference in lateral strength was only 15 percent, with one-cross strongest and four-cross weakest. Shorter spokes brace the wheel better from side loads than longer spokes. The surprise was that radial-spoked wheels were weaker laterally than one- or two-cross wheels. Price and Akers think that radial-spoked wheels are weaker because the uncrossed spokes don’t brace each other.

There was a similar variation in radial strength. Radial-spoking was strongest and four-cross was weakest. For some unexplained reason, one-cross wheels were out of sequence. They were about the same as four-cross.

From all of this esoterica, I conclude that there is no significant performance difference between three-cross and four-cross and that none of the other patterns make sense. I make my light racing wheels three-cross and my heavy touring wheels four-cross just in case there is any truth to the old saw that four-cross wheels ride softer.

How about all of the magic asymmetrical patterns that we always read about? For example, I used to make rear wheels radial on the right side and four-cross on the left. The rationale was that all of the pedaling torsional load was carried by the underloaded left side spokes. I used to get all kinds of comments. Then one day I was pedaling along and the rear wheel collapsed. The radial spokes tore a four-spoke wide chunk of metal out of my Dura-Ace low-flange hub. Lesson? The main reason not to build oddball patterns is that they’re hard to build; since the spoke tensions aren’t uniform, they don’t take advantage of all of the spoke’s strength.

_____ Frank’s Favorite Wheels _____

I use nothing but Shimano Dura-Ace Freehubs because I like the freewheel design so much. I must confess I haven’t had very much recent experience with any other hubs.

From his bicycle-repair-shop viewpoint, Paul Brown feels that middle- quality, cup-and-cone hubs are subject to a variety of quality and mis-adjustment problems. He feels that only the top-of-the line Campagnolo and Shimano Dura Ace hubs are as good as the sealed-bearing hubs from Phil Wood, SunTour, or Specialized.

I have two favorite wheels, one for loaded touring and one for fast sport touring. Both use Shimano Dura-Ace, wide-spaced 6-speed Freehubs. I use Wolber Super Champion Model 58 rims on my current loaded touring wheels. I’ll use Mistral M 20 rims on my next set. I use Matrix Titan rims on my lightweight wheels. Eric likes Mavic MA-40 rims. I use 36 Wheelsmith spokes on both sets of wheels. The touring wheels use straight, 14-gauge spokes laced four-cross. The light wheels use butted 14-16-14 gauge spokes laced three- cross.