More has happened to pedals in the past 5 years than in the previous 50. The big change is the strapless pedal systems that were introduced in 1986. A second significant change is the inclusion of pedals in most component gruppos. Before 1986, most serious riders used quill pedals made by either Campagnolo or by one of the small pedal companies. (The name “quill” comes from the turned up tab on the outside of the cage that keeps your shoe from slipping off. This tab resembles the nib of a goose quill pen. Quill pedals date back to the days when people still used goose quill pens.) Today, many serious riders are thinking about using something different. This section will outline your current options.

More good-quality 10-speeds use quill pedals than all of the other kinds of pedals put together. Quill pedals are used in three ways:

• With toe clips, tight straps, and cleated racing shoes.

• With toe clips, loose straps, and rubber-soled touring shoes.

• Without toe clips and with rubber-soled cycling shoes or running shoes.

If you’re using one of the above combinations, you shouldn’t be using quill pedals. (Now there’s a controversial statement.). If you’re in the first category, you should be using one of the new strapless pedal systems. If you’re in the second category, you should be using platform pedals. If you’re in the third category, you should be moving up to the second category, or you should be using double-sided rat-trap or mountain bike pedals. I’ll expand on the rationale for each of these assertions later on.

Anchoring Feet to Pedals:

For efficient pedaling, your feet have to be anchored to the pedals, and traditionally this has been done by means of toe clips and straps. Getting used to toe clips and straps is a difficult experience for most cyclists, who encounter them as adults rather than as part of the childhood process of learning to ride a bicycle. Perhaps a quarter of the adult riders who have mastered all of the subtleties of efficient bicycling still can’t hack toe clips and straps. If you’re in that category, all I can say is keep trying, the benefits are worth the effort.

Getting used to having your feet nailed to the pedals is mostly psychological. Some people start off with mini-clips and then move up to uncleated shoes and loose straps. Finally, they begin to tighten their straps. My observations are that only about 10 percent of adult riders ever progress to the point of using cleated shoes.

You can anchor your feet to the pedals with toe clips and straps or you can adopt one of the new strapless pedal systems. Either way, you improve your efficiency by spinning faster and applying power through more of the pedal circle. Only the short distance rider or city commuter should be without one system or the other. Let’s look at the advantages and disadvantages of the two systems.

Conventional Pedals with Toe Clips and Straps:

Toe clips and straps keep your feet in place on the pedals. There are two levels of rigidity, depending on whether or not you use cleated shoes. Prior to 1986, really serious riders used deep-cleated racing shoes with tight straps. With such shoes, you’re nailed to the pedals and your feet can’t rotate or pull out when you pull backwards at the bottom of the stroke. Cleated shoes keep your feet in place when you go over bumps. Because of the more rigid attachment, cleated shoes provide more pedaling efficiency than do toe clips and straps alone. You can spin faster and more smoothly and get more power out of your legs. Despite their advantages, there are four things wrong with cleated shoes:

• It’s a chore to lock onto the pedals and tighten the straps when you start off.

• You have to remember to loosen the toe straps before you try to get out of the pedals.

The tight toe straps act like tourniquets and cut off the flow of blood to your feet.

• Finally, cleated shoes aren’t made for walking, so as soon as you get off your bike, you have to change shoes.

In addition to the above disadvantages, many riders feel acute mental distress at the thought of being nailed to the bicycle, especially at low speeds. To avoid some of the disadvantages and to reduce the terror, many riders use uncleated touring shoes and ride with loose straps. This way you get about half of the efficiency benefits and a tenth of the terror. You put up with lower pedaling efficiency because it’s easy to get in and out of loose straps and because touring shoes are comfortable to walk on.

- Strapless Pedal Systems: The strapless pedal is an idea whose time has come. I think that most racers will be using strapless pedals within 2 years. The great mass of serious cyclists will use them as the costs come down and the best overall designs become accepted. With hindsight, it’s surprising that it took so long to improve on the old familiar shoe-pedal-toe clip-strap combination. Skis have used safety bindings for more than 20 years, but until now nobody thought to apply that technology to the much larger bicycle market.

All of the strapless pedal systems provide the efficiency of deep cleated shoes and they don’t cut off the blood to your feet. All of the systems are easier to get into and out of than conventional pedals with cleated shoes. Still, they’re for the kind of experienced riders who are comfortable with toe clips and straps. You’re rigidly attached to the pedals and you have to remember the release drill and practice it until it becomes automatic.

I’ve tested five current strapless shoe-pedal systems made by Adidas, AeroLite, CycleBinding, Look, and Pedalmaster. Each system has a different entry and exit drill. CycleBinding and Look are the easiest to enter and exit. They’re about the same as toe clips, straps, and touring shoes. All of the systems except CycleBinding are unpleasant to walk on. You can easily walk on CycleBinding shoes, though they are still not as comfortable for walking as touring shoes. Unfortunately, strapless pedal systems are expensive. They cost anywhere from $40 to $200, so you want to buy the right one the first time.

Basic Pedal Features

Before going into a more detailed discussion of the different pedal types and specific makes and models, let’s review the principle features of a bicycle pedal system. Take these features into account when you make your choice as to which system is right for you.

- Ease of Entry and Exit: I think that ease of entry and exist are the decisive factors in making the choice between the various strapless pedal systems, so I cover the differences at length in the writeups and in table -1. If you don’t feel comfortable getting in and out of your pedals, you won’t be happy with strapless pedals (nor with toe clips and straps).

= =

TABLE 1 Ease of Entry and Exit versus Pedaling Efficiency

- Shoe-Pedal System

- Ease of Entry/Exit

- Pedaling Efficiency

- Platform pedals, toe clips, loose straps, touring shoes

- Quill pedals, toe clips, tight straps, cleated racing shoes

- Rat-trap or MB pedals, no toe clips

- Strapless pedal systems

= =

In any pedal system there are actually three costs: pedals, shoes, and connecting hardware. If you have to throw away both your present pedals and shoes, it’s going to cost more to upgrade. The cost column in table 2 shows shoe and pedal prices for Adidas and CycleBinding, pedal and cleat prices for Look and AeroLite, and cleat and pedal adapter prices for Pedalmaster. Clearly I’m comparing apples and oranges since the prices reflect the different amounts of equipment. But, in each case, what is shown is the total cost of the components required to make the conversion to strapless pedals. TABLE 3 shows the cost of conventional pedals only.

- Weight: Pedals, toe clips, and straps are part of the bicycle weight. Weight freaks measure that in milligrams. Shoe and cleat weights are different because they’re worn. (Instead of worrying about a few ounces of shoes, maybe you should worry about those extra pounds of lard that are standing on top of the shoes.) Table 2 shows four weights: pedals, cleats, shoes, and total. I assume a 600-gram racing shoe for the systems that don’t include shoes. Table 3 shows the weight of just the pedals. To be comparable to the total weight in table 2, you should add about 130 grams for toe clips and straps, and 650 grams for cleated racing shoes, or 700 grams for touring shoes. The shoe weights are typical for a size 10½.

- Drag Angle: Larger drag angles let you pedal around corners leaning your bike farther over without dragging a pedal. Since this is critical for criterium racers, their bicycles have extra-high bottom brackets. Quill pedals and racing platform pedals are made as narrow as possible and the underside is cut away to improve the drag angle.

Drag angle isn’t nearly as critical for tourists as it is for racers. I’ve installed triple cranksets and 175mm cranks on all of my bicycles. Both changes worsen the drag angle. I surprise myself and scrape a pedal once a year or so, but it’s no big deal.

There’s a break point at about 25 degrees. With less than that, you’ll find your pedals scraping in normal cornering. Campagnolo quill pedals have a 30- degree drag angle. Most riders can live very comfortably with that. The new racing platform pedals and AeroLite have even better drag angles. But, bear in mind that most of us feel quite nervous with a bike leaned over as much as 35 degrees, Avocet tire advertisements notwithstanding.

Drag angle is affected both by pedal dimensions and by bicycle design. Bottom bracket height, crank length, and spindle length all determine how far you can lean over before you drag a pedal. Because the right crank is further outboard, the right drag angle is about 2 degrees smaller than the left. In countries where you drive on the right, the chain should be on the right in order to place the better drag angle on the left. However, the British, who invented the chain-driven bicycle, put the chain on the right side even though they drive on the left.

If you use a triple crankset and the longer triple spindle, the right-side drag angle will be about 1 degree smaller. If you use 175mm cranks instead of 170mm, the drag angle will be about 1½ degrees smaller. Conversely, 165mm cranks will increase the drag angle about 1½ degrees.

I built a jig to measure drag angle. I assumed a 10¾-inch bottom bracket height and I used a 170mm Campagnolo Record crankset with a Campagnolo 68-SS-120 double spindle. (The drag angle listed in tables 10-2 and 10-3 is the average of the left and right side drag angles.)

- Height: Height is the distance from the inside of the shoe sole to the centerline of the pedal spindle. The greater the height, the higher you have to raise your saddle and the higher your center of gravity. To measure height, I used the total distance rather than measuring from the outside of the shoe sole, because Adidas System 3 and CycleBinding require you to use their specific shoes. With conventional pedals and shoes, there’s more variation in the shoes than in the pedals. A thick-soled shoe and a cleat with extra material above the slot increases the height.

Table 2. Strapless Shoe-Pedal Systems. This model has a conventional cup-and-cone inner bearing, but a sealed cartridge needle outer bearing.

We rated cleated racing shoes. The distance from the inside of the sole to the top of the cleat slot varied from 0.25 to 0.75 inch between the different shoes. I used 0.5 inch (0.4 inch sole thickness and 0.1 inch cleat thickness) in TABLE 3 for measuring height on the conventional quill pedals.

We also rated rubber-soled touring shoes. The sole thickness varied from 0.3 to 0.5 inch between the different shoes. I allowed 0.4 inch for sole thickness in TABLE 3 when measuring height for platform, rat- trap, and mountain bike pedals. I also used a 0.4-inch sole thickness in my TABLE 2 height measurements for AeroLite, Look, and Pedalmaster systems.

- Service: Each kind of conventional pedal and each of the strapless pedal systems was designed for a particular kind of bicycling service. Tables 2 and 3 show my judgment of this service, whether it be racing, sport touring, loaded touring, or city riding.

- Bearings: Pedal bearings are smaller and more highly stressed than hub or crankset bearings. Pedal rpm is too slow for good lubrication and pedal bearing loading is cyclic because you push only on the downstroke. Moreover, pedal bearings take a lot of abuse from the water and grit splashed up by the front wheel. Adding insult to injury, most cyclists neglect pedal lubrication. Considering all of these factors, it’s amazing that conventional cup-and-cone ball bearings hold up as well as they do.

Pedals are the one place on a bike where sealed cartridge bearings make sense. All of the strapless pedal systems use high-quality sealed cartridge bearings of one kind or another. Adidas, CycleBinding, Look, and Shimano combine roller and ball bearings. AeroLite uses two cartridge roller bearings.

All good-quality conventional pedals either use cartridge bearings or cup and-cone bearings with a seal to keep moisture out of the inboard bearing.

Campagnolo and the Japanese Campy-copies use a spiral on the spindle. As the pedal revolves, the spiral grooves “screw” dirt and moisture away from the bearings. This works surprisingly well if you use lots of grease. The other top- quality pedals use close-clearance plastic bushings or labyrinth seals.

You get what you pay for with pedal bearings. Top-of-the-line pedals have hardened and ground races and cones, and you can feel the quality when you spin them. Lower-priced pedals use cruder manufacturing techniques, how ever, even poor-quality cup-and-cone bearings work adequately. Sutherland’s

Handbook for Bicycle Mechanics (4th ed.) says that most pedals have ten to twelve 5 balls per race. Campagnolo Super Record and Sakae use ¼-inch balls, but everyone else uses 5 balls.

For some strange reason, some pedal makers install one less ball than it takes to fill the race. I can’t believe this is an economy measure, so I suspect they’re anticipating that the bearings will never be serviced. When I was disassembling and inspecting pedals, I had to restrain myself to keep from pop ping an extra ball into the obvious gap.

Tables 2 and 3 show the type of bearings used and whether or not they have seals. The type of seal for most models is indicated in TABLE 3.

Walkability

Walkability depends entirely on the shoes. There’s a basic conflict between pedaling efficiency and walking comfort. Stiff soles protect your feet from pedal pressure, but they’re less comfortable to walk on. When you attach cleats to the bottom of your cycling shoes, walking becomes uncomfortable. If you walk on your cleats, they’ll wear out in short order.

The inverted cleat of the CycleBinding system is unique. You can walk on CycleBinding shoes. However, the slots fill up if you walk on soft dirt. (TABLE 2 shows my personal rating of the walkability of the five strapless pedal systems.)

Adjustability

With conventional pedals, you adjust the shoe-pedal fit when you install the cleats. Most good-quality racing shoes have some adjustability with their built-in cleats. There are two different adjustments with the strapless pedal systems. One is the ability to correct the alignment of a pedal-cleat system after you’ve attached the cleats to the shoes. With Adidas and CycleBinding, the shoe attachment is fixed, but you can modify the alignment of the pedal attachment.(Ease of adjustment for the different systems is rated in TABLE 2.)

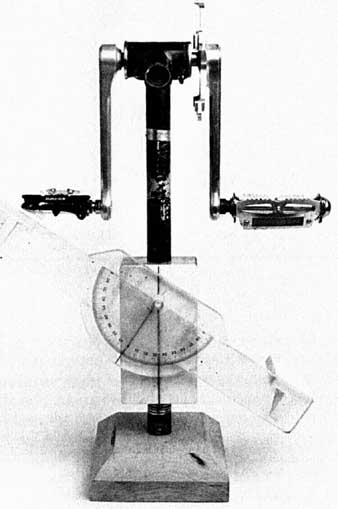

PHOTO 1: Drag angle measurement jig: left, Dura Ace pedal (34-degree drag

angle); right, counter weighted pedal (23- degree drag angle).

- Rigidity: The experts agree that for maximum pedaling efficiency, the shoe should be fixed to the pedal. There should be no back and forth, up and down, or side to side movement. However, there’s disagreement about rotation. Some experts think a small amount of rotation is desirable. When only toe clips and straps are used, there’s quite a bit of movement in all directions except forward. With cleated shoes, you’re fixed in all directions except up and down, which is why the racers cinch their straps so tightly. All of the strapless pedals are rigid in all three directions. They vary in the amount of rotation (TABLE 2 shows the approximate rotation).

- Release Torque: Release torque is the amount of twist that your ankle applies to rotate out of Adidas, CycleBinding, Look, and Pedalmaster pedals. Force times lever arm equals torque. It’s about 7 inches from a size 10½ ankle to the pedal spindle. Thus, a 10-pound release force produces a 70 inch-pound torque. Release torque is shown for most models in TABLE 2. I don’t show the AeroLite release torque because it’s applied in a different plane and the forces aren’t comparable. AeroLite torque varies significantly, depending on the tightness of the screws.

- Overstress Release: I think overstress or “safety” release is more important on the ski slopes than on the road. And with 60,000 trial lawyers waiting for the next Corvair, you won’t be reading much about the safety aspect of the new strapless pedal systems. However, there are significant differences between systems. CycleBinding provides the most complete overstress release. The Adidas literature talks about quick release in the event of an obstacle or fall. The other strapless systems only release in the designed direction. There’s precious little overstress release with deep cleats and tight straps, but there aren’t many broken ankles, even in the Category 4 demolition derbies.

I didn’t test overstress release in a formal way. Proper testing would have required comprehensive laboratory equipment and I’m not sure that it’s worth the effort. The ratings provided in TABLE 2 are thus based on my informal observations.

- Dimensions: With conventional pedals, you have to match the pedal’s dimensions to dimensions of your feet and your shoes. In TABLE 3, 1 list “shoe width” for the quill models, where your shoe has to fit between the shoe stop on the inside and the quill on the outside of the pedal (as shown in figure 10-1). I list the “front width” and “rear width” for the other kinds of pedals. The “gap” figures found in the table are measurements of the space between the cage rails on quill or track pedals and between the back rail and the front platform on platform pedals. (It is this space between rails that makes so many pedals uncomfortable with soft-soled shoes.) The “cage thickness” figures tell you how wide your shoe cleat must be, and are thus relevant only on models made to be used with cleated shoes.

-- Strapless Shoe-Pedal Systems --

Since the first strapless pedals appeared in 1985, five makes of strapless pedals have achieved significant distribution in the aftermarket; Adidas, Aero Lite, CycleBinding, Look, and Pedalmaster. I’ve tested each system and assembled relevant data into table 2.

FIGURE 1 Dimensions of quill pedals. [coming soon]

Adidas and Look are major companies who make other products besides pedals. Their pedals are imported from France. AeroLite, CycleBinding, and Pedalmaster are small American companies. Shimano has a license to use the Look cleat design. You’ll be seeing Shimano “Look-alike” pedals soon, but they were not available to me for testing at the time of this writing.

Adidas, CycleBinding, and Look use ski-binding technology. AeroLite and Pedalmaster have their own unique concepts. Adidas and CycleBinding come as shoe-cleat-pedal systems with shoes specifically designed for strapless pedals. AeroLite and Look provide pedals and cleats that you install on your own racing shoes. Pedalmaster provides clamps that bolt onto conventional pedals and adapter plates that bolt onto regular racing shoes.

Pre-1986 racing shoes were designed for toe clips and straps. “Animals” who really pull up may pull the uppers from the soles if they use their old shoes with AeroLite, Look, or CycleBinding strapless pedals. The new strapless pedal systems have caught on so well that most of today’s racing shoes are designed for strapless pedal service, and many of them are pre-drilled for Look cleats.

It would be wonderful if there were an American Bicycle Standards Association to develop a standard for strapless shoe-pedal systems. Our industry doesn’t work that way, so we have five different systems with five different entry-exit drills. I’ve pedaled all five and compared them, both in my workshop and out on the road. I used Look pedals on my 1986 summer tour of the Pacific Northwest.

I tested Look and AeroLite first. I installed them on two different bikes, planning to test them on alternate outings, just as I compare tires or derailleurs. That was a dumb idea. Twice, I braked to a stop, pulled, twisted, jerked, cursed, and toppled softly onto the asphalt. I had forgotten what I was pedaling and used the wrong release drill. After that experience, I revised my test procedure. For the rest of the tests, I pedaled each system for a month (about 300 miles) to get completely used to it. Then I wrote my impressions and switched over to the next system.

Take a lesson from my experience. Pick one system and take the time to get fully used to it. Install the same system on all of your bicycles. Each system has its own entry-exit technique, and it takes time for the technique to become second nature. All of the significant features are covered in TABLE 2 to help you make your choice.

- Adidas System 3: System 3 is French. The pedals are made by Manolo and the shoes are made by Adidas. Until now, U.S. distribution has been quite limited. The .shoes have ridges on the sides of the sole that engage with grooves in the fiberglass-reinforced pedals. According to the advertising, the pedal grooves are designed to release under excessive stress in all three positions. I didn’t test the overstress release.

System 3 is a combination of the very popular Adidas cross-country ski binding and the old Cinelli M 71 strapless pedal system. Cinelli M 71s were often called “death cleats” because there were just two positions: “lock” and “release.” You used a little tab to make the selection. In the “release” position, you could slide your shoe in and out of the pedal, but it was awkward to pedal because the shoe would pull out coming around the bottom. In the “lock” position, you were nailed to the pedals. The only way to get out was to push in the little tab. Track racers were the major users of these pedals.

Currently, there is only one System 3 model available, the Super Pro. The Super Pro pedal adds an intermediate position and overstress release to the M 71 design. A three-position lever on the pedal raises a stud partly in the second position and completely in the third position. The positions are called “town,” “road,” and “sprint.”

In the “road” position, you’re supposed to be able to rotate your foot out of the pedals, but the release torque varied and I couldn’t always jerk my foot out. With the pedal at the six o’clock position, I could usually get out with a combined twist and pull up. After a dozen or so false attempts, I always put the lever into the “town” position before pulling out. I treated System 3 like racing shoes with deep cleats. (It’s easier to turn the little lever than to loosen a tight toe strap on a conventional pedal.) I never used the “sprint” position because I never came close to a false release in the “road” position.

It’s easy to get into the System 3 pedals, much like a conventional pedal with toe clips. I also liked the Adidas STi shoes. They use Velcro closures and straps instead of laces; they were very comfortable pedaling and fairly comfort able walking. There’s no cleat but there’s also no heel. Adidas now makes three System 3 shoes: one for road racing, one for track racing, and one for touring.

- AeroLite: AeroLite is a small American company started by inventor Roger Sanders. The AeroLite system isn’t based on a ski binding; it’s uniquely designed for bicycles. The other four systems all have a rotate-to-release drill, in which you push your heel out. AeroLite has a roll-to-release drill, in which you push your knee out.

The AeroLite pedal will be controversial because it’s unique. Riders will either love it or hate it. Look at TABLE 2. This pedal system rates at the top or the bottom in almost every category—for example, it’s lightest in weight and offers the best drag angle, but it’s the poorest for walking. The AeroLite system is elegantly simple. The pedal is a spindle with a roller, and the cleat is a wide, plastic C-clip attached to the sole of the shoes with four screws.

You attach yourself to an AeroLite pedal by placing the cleat on the spindle and pushing down hard. You release by rolling your foot sideways and pulling free. I found that this worked best at the 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock positions. I developed a roll-and-jerk action to counteract the cleat’s tendency to hang on to the end of the roller. There’s only one adjustment—the tightness of the four screws that attach the cleat. Tightening the screws squeezes the cleat together, making it harder to clamp onto the pedal and harder to pull free. It’s more pleasant to ride with loose screws. However, if they’re too loose and you’re a strong rider, you may pull out of the pedal on the upstroke. So the adjustment is critical. I got them just right after I took a Phillips screwdriver with me on a ride and tightened the screws a quarter of a turn at a time.

AeroLite had startup problems with the cleats sliding sideways on the roller pedal. They went through three different fixes before they finally licked the problem. The current cleat has a stop on both ends. With more and more shoes coming pre-drilled for Look cleats, AeroLite developed an adapter plate that bolts onto the three Look holes and is pre-drilled for AeroLite cleats. AeroLite is the favorite of serious triathletes. I expect to see AeroLite pedals on ultra-light bicycles. AeroLite recognizes the weight-freak market and they make a special super-light titanium model.

AeroLite is the least expensive and lightest of the five strapless systems, and has the best drag angle. You’re solidly attached to the pedal. There’s no overstress release on ankle rotation. In fact, your shoes don’t rotate at all. You “wear” your bicycle just like you do with deep cleats and tight straps. The difference is that there’s no strap to restrict your circulation and there’s a no- hands release drill.

The AeroLite pedal is a roller, so it’s difficult to start out or to pedal when you’re not clamped on, because your shoe tends to slip off. I learned to put the cleat behind the roller and not push too hard. I also learned to clamp one pedal before I swung onto the saddle. Finally, the shoes are hard to walk on, just like racing shoes with deep cleats.

- CycleBinding: CycleBinding is a new company founded by Rick Howell, who used to work for the Geze ski-binding company. CycleBinding makes racing, triathlete, and sport shoes, as well as racing and sport pedals. The CycleBinding and Look systems are quite similar. CycleBinding is closer to Geze ski bindings, while Look is closer to Look ski bindings. Skiers might find it useful to select a pedal system to match their ski bindings. The key difference between them is that

CycleBinding is a shoe-pedal-cleat system with the female element molded into the shoe sole. Look is a pedal-cleat system and the male cleat protrudes from the shoe sole. The flat-soled CycleBinding shoes are much more comfortable to walk on.

The CycleBinding pedal is dropped like the old Shimano Dyna-Drive. Rick Howell set out to improve on what he saw as limitations of Shimano’s design. The pedal is elegantly engineered with top-quality bearings and seals. The pedal is self-righting so that the male element, called the powerhead, always faces up. You lock in with an easy push and twist motion. In fact, it’s so easy that I sometimes locked in unintentionally when I rested my foot on the pedal after releasing. The shoe is rigidly locked onto the pedal in all directions.

You release from the CycleBinding pedal by rotating your foot sideways. The release torque is more than Look and less than Adidas. The shoe is restrained against rotation until you exceed the release torque and then it releases with a snap action. I could easily get out at any crank position. The CycleBinding system has overstress release in other directions when the torque or the force approaches a critical level. My test setup used a 50-pound scale. The overstress releases took more than 50 pounds, so I only measured the release torque.

PHOTO 2: Strapless shoe-pedal systems: left to right, Adidas System 3 pedal

and shoe, AeroLite Pedal and Diadora shoe, CycleBinding Competition pedal

and shoe, Look Sport pedal and shoe, and Pedalmaster adapters on Galli pedals

and Vittoria shoes.

- Look: Look strapless pedals have been race-tested since 1984. Look is a pedal- cleat system. You can bolt the cleats onto any hard-soled racing shoes. I tested all three Look pedals: the black Competition, the white Sport, and the black and yellow plastic models that started out named Leisure and were renamed ATB when they became so popular with the all-terrain bikers.

All of the Look pedals are substantially built using industrial ball and roller bearings. The locking mechanism on all three hangs below the centerline giving an average drag angle. The Sport and ATB (Leisure) models are wider so their drag angles are worse.

The Look cleat is substantial, though not too thick. It’s easier to walk on Look cleats than on AeroLites, Pedalmasters, or racing shoes with deep cleats, but you wouldn’t enjoy walking up a long hill. (On my 500-mile tour, I carried a pair of Hush Puppies in my panniers and changed as soon as I got off the bicycle.) Look makes a range of shoes. All feature Velcro straps that make them very easy to slip on and off.

The Look pedal hangs with the back down. Locking in is easy. You push the front of the cleat forward against the pedal and push down. Getting out is even easier. I’m most comfortable with the adjustment set at the minimum. But even with the adjustment turned to maximum, you can rotate your foot out in any crank position. I’m comfortable braking to a stop and pulling out at the last moment. The Look binding is rigid in all directions except rotation. Your shoes can rotate on the pedals about 5 degrees. If you rotate beyond that, you release. Depending on the advertising you believe, freedom of rotation may or may not be ergonomically desirable.

- Pedalmaster: Bicycle Parts Pacific (BPP) is an importer whose lines include Galli pedals and Vittoria shoes. After the first strapless pedals had been on the market for two years, Darek Barefoot of BPP got a brilliant idea. Many cyclists were going to want strapless pedals, but they wouldn’t want to throw away their perfectly good quill pedals. As new bicycle customers bought strapless pedals, the bicycle stores were going to be swamped with brand-new non-strapless pedals. The Pedalmaster system was designed to fill that need.

For $40, you get a set of front and rear clamps to bolt onto your quill or platform pedals and a set of shoe plates to bolt onto your racing shoes. You fasten shoe to pedal by pushing the front of the shoe plate into the front pedal clamp. Then you swing your heel inward so that the loop at the back of the shoe plate engages the hook on the back of the pedal. You swing your heel outward to exit. I pedaled a Pedalmaster set for 300 miles or so. I found this system harder to enter and exit than the Look or CycleBinding systems and easier than the AeroLite system. Once locked in, you’re rigid in all directions. Your shoe is about ¼ inch higher than it would be with conventional cleats The pedal dimensions and features depend on the pedal that you adapt in this way.

- Overall Comparison: With strapless pedals, you’re dealing with a new product and the players in the marketplace are still learning their roles. Now that Shimano is making Look-licensed pedals, the Look system is the one to beat—widely advertised and widely available. You can expect Shimano to introduce lower-priced versions year by year. The present Look pedals are solidly built. Entry and exit are easy and reliable and your shoes can rotate a bit.

The CycleBinding system appeals to the person who wants all of the features and is willing to pay for them. CycleBinding’s comfortable walking shoes are very appealing, but you have to buy the complete shoe-pedal package from CycleBinding, and they don’t come cheap.

Pedalmaster appeals to the other end of the price spectrum. It’s not as convenient to enter and exit as most of the others but it lets you use your present shoes and pedals.

AeroLite will find a. major market because of it’s low weight, splendid drag angle, and low price. It’s unique entry/exit drill takes some getting used to. For racers and triathletes, it has all of the advantages of racing shoes with deep cleats and it beats them hands down.

“Looking” at the competition, I don’t think Adidas System 3 will survive in the USA. The lack of a completely predictable exit in this system and the limited distribution is too much of a handicap.

-- Types of Conventional Pedals--

If you stick with conventional pedals, be aware that there are important differences between the various types. Pick the type that suits you. There are two main categories: single-sided and double-sided. When I wrote my first pedal article in 1983, 1 weighed, disassembled, and measured 60 different pairs of conventional pedals. For this section, 1 picked the best of the 60 and added 20 conventional pedals that have appeared on the market since 1983.

- Single-Sided Pedals: Single-sided pedals are designed for toe-clips and straps. Toe clips come in three or four lengths: short, medium, large, and sometimes extra large. Lengths aren’t standardized, and the French sizes are a bit larger than the Japanese. Buy a toe clip length that positions the ball of your foot over the pedal spindle. You can now buy reinforced plastic toe clips from Specialized. That’s a nice idea. They don’t rust and they don’t chew up your shoes as quickly.

If you don’t use toe clips, you still have to kick the pedals right side up every time. The three types are: quill, track, and platform. Each type matches a different kind of rider and a different usage. Let’s look at each one in turn.

Quill Pedals

If your bicycle is more than two years old and it cost more than $300 new, it’s probably equipped with quill pedals. They may be the right choice for you, but you should take a serious look at your riding style. The quill is a racing pedal designed for toe clips, straps, and cleated shoes. If you use cleats, then one of the strapless systems may be a better choice for you, because they offer easier entry and exit and there’s no tight strap to cut the blood circulation to your feet.

When you buy cleats, check that the cleat slot is wider than the thickness of the pedal cage. Occasionally, narrow cleat slots will have trouble fitting onto pedals with thick cages. A few file strokes through the slot will “open” your cleats to fit a fat cage. (TABLE 3 shows cage thickness.)

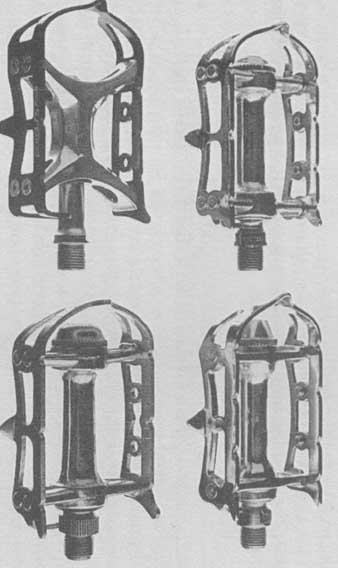

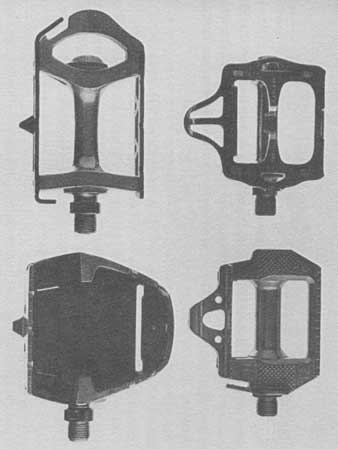

PHOTO 3----Quill pedal quality levels: top left and right, Campagnolo Nuovo

Record (top-quality) and Maillard Spidel (top-quality); bottom left and right,

SunTour Superbe Pro (medium-quality) and MKS Sylvan (economy- quality).

If you pedal in uncleated shoes, you’ll be more comfortable with a platform pedal that provides a broader surface to support your shoes. However, it’s not a big improvement and you may decide to stick with your quill pedals. If you don’t use toe clips and straps, you’re much better off with a double-sided pedal.

Quill pedals are made as narrow as possible and the underside is cut away to improve the drag angle. If you wear a wide shoe, you’ll be in trouble with quill pedals because they’re designed to match narrow European racing shoes. Wide shoes ride on the inside shoe stop and the quill instead of the flat cage. This is particularly uncomfortable on the quill pedals with high inside stops. Most quill pedals have an inner shoe stop in addition to the outer quill. The stop and the quill keep your feet from slipping sideways on the pedals.

I call the spacing between the two stops the “shoe width” and it’s listed in TABLE 3. It varies from 3.4 to 4.0 inches for quill pedals, although some models omit the inner shoe stop. You could grind or file it off the other pedals without too much trouble, which lets you use a wider shoe. If you find that your quill pedals are gouging crevices in your wide shoes, consider switching to strapless, track, or platform pedals.

Because quill pedals are so universal, they come in four price/quality levels: super-quality, top-quality, medium-quality, and economy. Campagnolo’s $300 Super Record, which has titanium spindles and their $200 C-Record make up the super-quality class.

Top-quality quill pedals are either Campagnolo or something that looks very much like a Campagnolo quill. They have forged, one-piece aluminum alloy bodies, aluminum or steel cages, precision ground bearings with effective inside bearing seals, and chrome-moly spindles. There’s usually considerable hand polishing. They weigh 300 to 350 grams with aluminum alloy cages, and 400 grams with steel cages. Prices run in the $100 to $150 range. Aluminum cages get chewed up in 10,000 miles or so, but steel cages last forever.

Medium-quality quill pedals costing $30 to $60 are very adequate pedals. The aluminum alloy body may be cast instead of forged. It certainly won’t be hand polished. The cage will be steel or aluminum. The MKS Unique Custom Campy-copy is the bargain in this price range. The SunTour Superbe Pro is the top performer.

Economy quill pedals sell for about $15 per pair. There are two kinds. One has a body swaged together from separate pieces of steel and aluminum. The other has a melt-forged, one-piece body and cage.

All quill pedals are drilled for toe clips. On the higher-quality pedals, the toe clip mounting holes are threaded and the bolts and washers are included. Many of the newest models have bodies shaped like a letter X rather than the usual letter H. This moves in the outer bearing and improves the drag angle.

Track Pedals----Every top-quality quill pedal has a track brother. The spindles and bodies are identical, but the track pedal has two separate cage plates instead of the wrap-around quill cage. Track racers don’t use quill pedals in order to avoid sharp projections that might gouge an adjacent racer. Also, since the strap doesn’t pass outside the quill frame, it holds the shoe more securely (and cuts off circulation to the feet more completely). The average pair of track pedals weighs 10 to 20 grams less than the comparable quill pedals. Most track pedals don’t have an inner shoe stop so they depend on the straps to keep your feet from sliding sideways. Not all track pedals have a shoe pickup tab, but even so, they’re not reversible. They have a top and a bottom, and they’re designed for use with toe clips and straps.

I don’t show the companion track pedals in TABLE 3. I do show the new breed of road-track pedals that came on the market when road racers started to use track pedals. These new “track” pedals have narrower front cages, lighter weight, and better drag angles. Since there is no outer shoe stop (quill), you can use wider shoes.

Platform Pedals----For many riders, platform pedals make more sense than quills and there’s a wide assortment of sexy-looking models to choose from. However, since both quill and platform pedals are designed for toe clips and straps, the real competition is the strapless pedal. There are two kinds of platform pedals: racing and touring.

Racing platform pedals have a triangular shape with the front rail replaced by a platform for the front of the shoe. They have the following advantages over quill pedals:

• There’s no outer quill or inner shoe stop so you can use wider shoes.

• It’s easier to lock into the toe clips since platform pedals hang straight down instead of upside down. Many models have effective shoe pickup tabs.

• They’re lighter than quill pedals.

• They have a better drag angle than quill pedals.

• Many have adjustable toe clips so you can fine-tune the toe clip length and the toe clip angle. Standard toe clips don’t fit these new platform pedals and each requires its own unique toe clips. If you wear large shoes, you’ll need XL toe clips, and these aren’t always available. Make sure you buy the right length toe clip when you buy the pedals. With most toe clips, the amount of adjustment is typically limited to the difference between toe clip sizes.

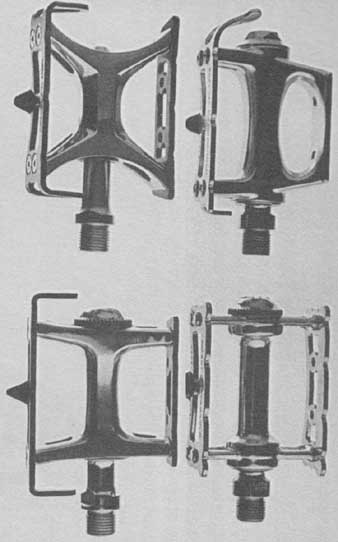

PHOTO 4: Track and track-style road pedals: top left and right, Campagnolo

C- Record (road racing) and Campagnolo Nuovo Record (track); bottom left

and right, SunTour Superbe Pro (track) and Specialized Racing (road racing).

Many platform pedals are streamlined. This seems like a dubious benefit, since the turbulence generated by the front wheel, the leg, and the foot overwhelms the benefit of streamlined pedals.

There’s a small group of touring platform pedals that really provides a flat platform to support your shoes. Buy these pedals if you use rubber-soled touring shoes. Touring shoes compromise sole rigidity to provide flexibility for walking. These pedals usually have a vestigial rear rail, but it’s designed for slotted shoe soles rather than deep cleats. If you use quill pedals, your feet are supported on the two cage rails 2 ‘4 inches apart and you can feel the rails through the soles. Racing platform pedals have a 2-inch gap between the front platform and the projecting rear cage. Your toes rest on a platform, but that’s all. The Lyotard Berthet was the first touring platform and the Sakae SP- ills similar. The Specialized Touring looks like a quill pedal at first glance. Then you notice that the end frames provide a flat support for your soles. The Shimano Triathlon has a plastic insert to fill the gap.

-Double-Sided Pedals: Many users of quill or platform pedals don’t use toe clips and straps. That’s a poor pedal selection, unless you’re planning to install toe clips and straps later. If you don’t use toe clips and straps, you’re much better off with double- sided pedals. They have a better gripping surface for your shoes and there is no upside-down position. Why put up with the hassle of kicking the pedal over to get it right side up. The four kinds of double-sided pedals are: rat-trap, mountain bike, rubber block, and counterweighted. Double-sided pedals are de signed for use without toe clips and straps. You can install toe clips on many double pedals, but that converts them to single-sided pedals with a poor drag angle.

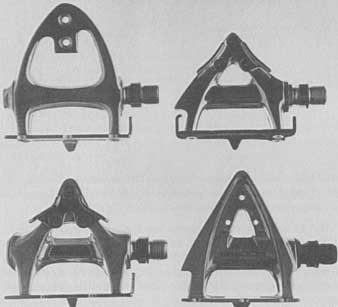

PHOTO 5: Racing platform pedals: top left and right, Campagnolo C-Record

and Shimano Dura-Ace; bottom left and right, Shimano 600 EX and Shimano 105.

Rat-Trap Pedals----Ten years ago, most low-priced 10-speeds used rat-trap pedals. Today, counterweighted or economy quill pedals have largely replaced rat-traps. This is a retrograde step for the beginning bicyclist. A rat-trap pedal is basically a wide track pedal with no pedigree. The main advantage is that it’s reversible. If you don’t use toe clips and straps, you should use double-sided pedals. Rat-trap pedals have an uncouth image. They’re only used on inexpensive bicycles, and the name sounds antisocial. The pedal catalogs show a range of widths and quality levels, but most bike stores carry only the $5, bottom-of- the-line replacement rat-trap. These “bargain-basement” rat-traps are fairly wide, and their bearings can’t be disassembled. When they start to creak, you throw them away. The cage of the standard rat-trap is about 3¾ inches wide and they drag at about 25 degrees.

PHOTO 6: Touring platform pedals: top left and right, Lyotard Berthet and

Sakae SP-1 1; bottom left and right, Specialized Touring and Shimano Triathlon.

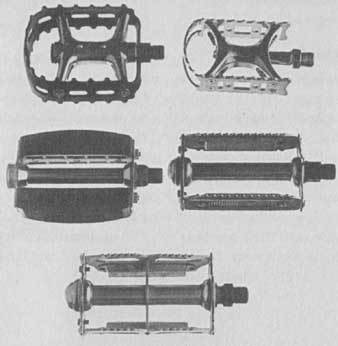

PHOTO 7: Double-sided pedals: top left and right, Shimano Deore XT (mountain

bike) and SunTour XC-Compe (mountain bike); middle left and right, Lyotard

rubber block and a rat-trap pedal; bottom, a counterweighted pedal (with

bent frame).

Mountain Bike or BMX Pedals---- If you want a high-quality, hell-for-stout rat-trap pedal, ask for a mountain bike pedal. (There’s no basic difference between mountain bike and BMX (bicycle motocross) pedals, except that BMX pedals are often anodized in flamboyant colors.) Some mountain bike pedals have very aggressive serrations on their cages to retain shoe contact in gonzo descents but most of them are reasonably conservative.

Mountain bike pedals are widely sold so they come in a range of qualities. The best models have excellent sealed bearings designed for underwater biking in scuba gear. Many mountain bike pedals are designed for toe clips and straps. That may make sense for mountain biking but a single-sided pedal with, toe clips and straps is better for road use. Many mountain bike pedals are made of reinforced plastic for lightness and corrosion resistance. These pedals have been thoroughly tested in off-road service so you can rest assured they’re not “cheap plastic” imitations. Drag angle on these pedals varies but it’s often better than that of a rat-trap pedal.

Rubber Block Pedals ----Rubber block pedals share most of the advantages and disadvantages of rat-trap and mountain pedals. They don’t accept toe clips and straps. The significant difference is the surface your shoe rests on. The cage of a rat-trap or mountain bike pedal is serrated to grip soft shoe soles. The serrations press uncomfortably through thin soles and they do a poor job of gripping leather soles. By contrast, rubber block pedals are designed for thin soles or leather-soled shoes. The pedal catalogs show a wide range of rubber block pedals, but the typical bike store stocks only the bottom-of-the-line replacement models.

Counterweighted Pedals----I mention counterweighted pedals last because they’re a rotten design with no redeeming virtues. If your bicycle has counter- weighted pedals, replace them with a type that suits your needs.

In theory, the counterweighted pedal is a reflectorized rat-trap that accepts toe clips without removing the reflectors. The reflectors on a counterweighted pedal hang below the spindle frame and act as counterweights to keep the pedal right side up. If you install toe clips, a counterweighted pedal hangs upside down like any other pedal. If you don’t install toe clips, the counter weights don’t always work. When you stomp on the bottom of the pedal, the cage bends, rendering the reflectors useless. The counterweighted pedal has the worst (and least safe) drag angle of any pedal. Today, few new bicycles use counterweighted pedals and I use them as a litmus test for sloppy bicycle design.

-- Conventional Pedal Makers --

The pedal market is shaking out. As more and more bicycle makers buy their pedals as part of Shimano, SunTour, or Campagnolo gruppos and the replacement buyers opt for strapless pedals, there’s very little business left for the small maker of conventional pedals. Here’s the current market situation.

- Campagnolo: Campagnolo dominates the quill pedal market. They make models at four price levels. Each quill has a companion track model. The Super Record pedal is an exotic model with a titanium spindle and ½-inch ball bearings to bring the weight down to 259 grams. Titanium is inherently weaker than steel, and the racing scene abounds with stories of failed titanium pedals. Super Leggeri (Super Light) is the pedal that you get in most Super Record gruppos. It has a black aluminum frame. Record Strada (Road) has a chrome-plated steel cage. All three are equally polished. Gran Sport is the middle-priced model and it’s not widely available. Since they were introduced in 1985, Campagnolo has been struggling with their C-Record, Victory, and Triomphe platform pedals. They’re things of beauty but the racers keep buying the old quill pedals. Campagnolo introduced a new C-Record road-track pedal in 1987 that looks more like a quill pedal and repositions the foot support point.

- Lyotard: Lyotard was making pedals in France before I was born. The Lyotard Berthet platform pedal is a classic design and a bargain, if you can locate a pair. Lyotard makes good-quality rat-trap and rubber block pedals, but these designs are no longer fashionable, so they’re hard to find.

- Maillard (Galli): Maillard, the quality French pedal maker, is now part of Sachs-Huret. Galli sells the Maillard 700 quill pedal as the Galli Criterium. There’s no inner stop on Maillard quill pedals, so you can use a bit wider shoe. Both companies make a whole range of pedals, but distribution is spotty.

- MKS: MKS (Mikashima Industrial Co.) is Japan’s largest pedal manufacturer. They make a complete range of pedals, and U.S. distribution is fairly good. MKS makes SunTour’s and Specialized’s pedals. The Unique Custom is the middle- priced Campy-copy quill and the Sylvan Road is the lower-priced model. The 255-gram MKS RX-1 (217 grams with titanium spindles) is the lightest conventional pedal that I know of. The Grafight-2000 and the Grafight-X are the rein forced fiberglass mountain bike pedals.

- Sakae: Sakae Ringyo (SR) has used their Silstar aluminum casting skills to make a very complete line of low-to-middle priced pedals with one-piece die-cast bodies. Most of them are sold in the OEM market. The SP-1 1 is a touring platform modeled after the Lyotard Berthet.

- Shimano: Shimano broadened its line to include pedals, but it’s been one area where they haven’t made a great impact. I suspect that this is what led to the decision to make a Look-based strapless pedal. (If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.)

Part of Shimano’s problem was their Dyna-Drive concept, which never caught on. Dyna-Drive pedals featured a unique dropped platform design that minimized height. Shimano installed both bearings at the crank end and cantilevered the pedals outward. The top of the platform was right at the bearing centerline, rather than ½- to ¾-inch above the centerline. Shimano claimed all sorts of ergonomic advantages for Dyna-Drive, but after three years of advertising, they quietly dropped the design. I never noticed any pedaling improvement with the dropped design, but it was easy to get into the toe clips.

Although it’s not shown in the catalogs, you can still buy Dyna-Drive pedals and cranks. They use a special oversized pedal thread and Shimano doesn’t want to leave the old users high and dry. The dropped platform idea has resurfaced in the CycleBinding strapless pedal.

Shimano’s Dura-Ace, 600 EX, and 105 pedals are very similar aerodynamic platform models with excellent bearing seals and drag angles. Shimano’s Triathlon pedal is great for touring in touring shoes. The Deore XT is their mountain bike pedal.

- Specialized: Specialized went to MKS and ordered two pedals to their specifications. The racing model was one of the first road racing “track” pedals. The touring pedal is the best of the breed in my opinion. It offers good support for soft-soled shoes.

- SunTour: SunTour now has pedals made by MKS for each of the SunTour gruppos:

Superbe Pro, Sprint, Cyclone, and XC-9000 and XC-Sport 7000. The Superbe Pro quill pedal shows up the weakness of Campagnolo’s old quill pedal design. The Superbe Pro has less weight, a better drag angle, sealed cartridge bearings, and a replaceable cage. Before the yen went through the roof, it sold for about half the price of the Campagnolo Super Light. The XC-Compe, which serves both XC gruppos, is SunTour’s top-quality mountain bike pedal.

- Everybody Else: There are a lot of everybody elses. Competition came late to the pedal business. KKT, a major Japanese maker, is now bankrupt. Excell, Gipiemme, Mavic, Stronglight, and Zeus all make very good racing pedals. The market is shrinking and their U.S. distribution is spotty.

- Favorite Pedals: I have Shimano-Look strapless pedals on one racing bike and Look Sports on the other. I like them and I think they improve my pedaling efficiency. I adjust the release setting of the Looks as low as it will go. I have CycleBinding pedals on my two touring bicycles. CycleBinding and Look have a similar release drill. I have Specialized touring pedals with toe clips and straps on my commuting bike so that I can use regular street shoes.