[Cont. from Maintenance--part 1]

Brakes

Although their efficiency leaves something to be desired, especially when wet, brakes on a bike seldom fail spontaneously. They are a reliable component if given regular preventive maintenance.

Caliper-brake stopping power on a loaded touring bike is marginal at best so anything you can do to increase it’s extremely important. Think about a 150- pound tourist riding a 30-pound bicycle with 30 pounds of gear; that is 210 pounds going 25 mph or more downhill. Now look at the little brake pads and thin cables that make up your braking system. When the time comes, especially in a panic situation, you had better be sure those brakes are in top working order and excellent condition.

Although brake design has some effect on your ability to put maximum force on the brake pads, the most critical aspect is the amount of lever travel. If your brake pads are farther from the rim than they should be, you are losing stopping power. If the pads are worn, dirty and imbedded with foreign material, you are losing stopping power. If the pads are out of adjustment so that only part of their surface area makes contact with the rim, you are losing stopping power. Can you afford it?

Check the condition of your brake pads. Are they worn past the grooves (not all pads have grooves, be sure yours did before you panic)? Press hard into the edge of the pad with your fingernail. Does it sink in slightly or does it feel as though you are pressing on wood? Most brake pads need replacement due to old age rather than actual wear. As the pad ages, especially when exposed to sunshine, it hardens so much that it loses much of its frictional quality. To keep your pads in good condition, clean them occasionally with a toothbrush dipped in alcohol or other mild cleaning agent.

When your pads need to be re placed, you will discover a wide variety to choose from at most bike shops. We haven’t had the opportunity to test many of them, so cannot speak authoritatively on their individual merits. Of the newer, exotic pads available there are many manufacturer’s claims but the only one we have heard fairly consistent positive reports about is the Mathauser brake block. At around $15 per set we haven’t felt the necessity to switch, but if you have braking problems or use caliper brakes on a tandem, you might try them out. Our personal choice through the years is Weinmann Vainqueur, a pad with four large segments on the face. A full set (four) can be had for about $3 — a good price for a good product.

You need certain tools to replace your brake pads. A 6-inch adjustable (crescent) wrench is the most all around bicycle tool. There is a trend toward more allen head bolts (bolts with a small hole for insertion of an alien wrench); check your bike for nuts and bolts versus alien bolts to see if you should invest in a high-quality, 6-inch adjustable wrench ($4-$7). If you plan to take full charge of your brake maintenance, get a set of brake wrenches. These come in sets of two, usually a 10- millimeter open end/8-millimeter box end and a 9-millimeter box end/10-millimeter box end. The best set we know is the Dia-Compe, which is a joy to use around brake bolts and frame members due to its bent ends ($6 and up).

When replacing brake blocks or pads, make absolutely sure that the en closed metal portion that holds the pad in place is to the front of the bike. Some brake blocks have one end uncovered for ease in replacing the pad; never put that uncovered end forward or you might see your brake pad preceding your bike downhill the first time you put on the brakes hard.

To replace the pads, remove the brake blocks from the yoke arms by un doing the retainer nut, then push out the old pads and put in the new. Much easier and what we recommend is to re place the whole block. When you put the brake blocks back in the yokes, make sure they are aligned so the pads are of equal distance from the rims. To do this, loosen the nut that holds the en tire brake unit on the frame just enough so that you can pivot the brake system until it’s aligned. Another way to do this is to first make sure the nut holding the brake on the frame is snug — using a3 solid line punch (or a long / or ¼-inch bolt) against the steel spring on each side of the brake — tap it until the brake system shifts to a centered position over the rim. Don’t put the punch against the brake yokes as this will scar them. Centerpull brakes can be centered using the punch against the springs or by using a 4- to 6-inch piece of wooden dowel against the yokes themselves without damage. Sidepull brakes must be centered with a punch on the springs; some sidepulls have a narrow slot near the main bolt attachment where you can straighten them with a narrow, 10-millimeter open-end wrench.

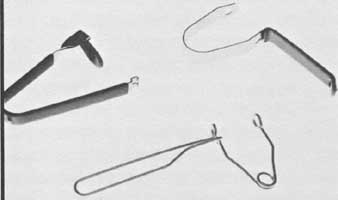

Specialized brake-adjusting tool; Brake blocks showing

open and closed ends on shoes.

When the brake is centered so there is equal space between the pads and the rim adjust the pads vertically to sit on the rim properly. To do this, squeeze the brake lever so the pad is firmly on the rim. It should be just down (V inch) from the top edge of the rim. If not, loosen the nut that holds the block in the yoke and move the block to the right position. While squeezing the brake lever, tighten the nut by hand. Then release the lever, grip the brake block carefully (don’t move it) with your adjustable wrench and firmly tighten the nut with a 10-millimeter wrench.

Once the pads are perfectly aligned both laterally and vertically, take up any slack in the brake cable so the brake shoes are as close to the rim as the trueness of the wheel will allow. If your wheels are out of true by more than Vs inch you should true your wheels or have it done before you adjust the brake cable.

Top view of brake pads close to and with equal distance between

pads and rim; When adjusting brakes with 3 solid line punch,

make sure the punch is against the steel spring, rather than against the

alloy portion of the brake.

A friend will do but a third hand tool makes adjusting the brake cable much easier. This inexpensive spring-steel tool compresses the pads to the rims al lowing you to use both hands to take up the cable. Third hand tools for home use cost $1.50-$2.50. Using the tool or someone’s hands compress the pads against the rims; check to see that your brake-release mechanism is closed, then look for the cable-tension adjuster either on the yoke of sidepulls, on the cable hanger assembly of centerpulls, or on the brake lever housing of some models. If the cable is only slightly loose, take up the slack by unscrewing (raising) the adjuster. If the adjuster is not already screwed to its maximum position, thus lengthening the cable housing that in turn puts more tension on the cable, you have some room to maneuver here. The adjuster sometimes has a small barrel nut to lock the adjuster nut in place; be sure to run it all the way down after making your cable housing adjustment.

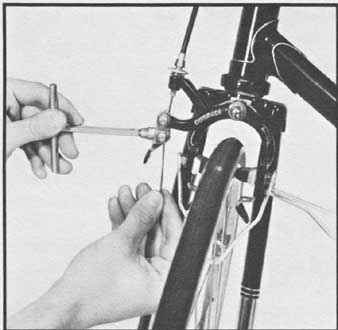

A properly adjusted brake block has a pad 1/32- 1/16 inch down

from the top of rim; While tightening the brake block nut with

a ten- millimeter brake wrench, hold the brake shoe (metal part) with a

six-inch adjustable wrench.

A variety of third hand tools.

If the brake cable is slack with the adjuster nut or nuts at maximum, pre pare to work on the cable itself — but first put the adjuster nut at its lowest position so it can be used for minor adjustments in the future. With either your adjustable wrench or your brake tools, loosen the nut on the pinch bolt that holds the cable in place on the brake itself (sidepulls) or above the brake (centerpulls). Loosen this nut until the cable can be pulled through the hole in the pinch bolt to tighten it. When you have pulled the slack out of the cable (remember to hold the brake pads firmly against the rims), tighten the pinch-bolt nut. Pliers are useful for pulling on the cable while tightening the nut, but not necessary. If you have done all this right, when you release the brake pads they should rest as close to the rim as possible — without touching — as the wheel turns. If they are touching the rims you will have to loosen the cable a fraction, but this is unlikely. Don’t be discouraged if it takes you several trys to get it right; once accomplished, exact brake adjustment is yours for the doing.

Cable-tension adjusters found on: brake lever (Mafac type) (A),

cable hanger assembly on centerpulls (B), brake arm of sidepulls (C).

Periodic brake maintenance includes oiling of the pivot points. If you ride with fenders and keep your bike clean, you should oil your brakes every three or four months. Dirty, dusty conditions and bad weather dictate more frequent lubrication.

Third hand tool in place, cable-tension adjuster screwed down,

brake wrench on pinch nut, and other hand pulling cable to adjust length.

When your wheels are off your bike (now if you are following our advice for hands-on practice), squeeze the brake arms together with your hand then re lease them. Observe and feel how they open and close. The movement should be smooth and precise; if not, several drops of oil in the pivot point of the yoke arms should solve the problem. First, clean the area to be oiled with a rag, then drop the oil in carefully. Wipe off excess oil.

When in doubt, the tendency is to spray everything with some sort of fine oil spray. This is not the way to oil a bi cycle. Oil does more harm than good if sprayed indiscriminately; it attracts dirt. Most fine sprays like WD-40 are not thick enough to lubricate adequately.

They penetrate and loosen stuck mechanisms but leave no long-lasting residue. A general rule is to oil only at the point of friction. Use an oil with adequate holding properties.

The type of oil is up to you. On brakes and derailleurs, any medium- weight or lightweight oil is fine; 20- weight engine oil, LPS-3 (not LPS-1 or WD-40), special bicycle oil, Sturmey Archer or other oil of a petroleum base. Vegetable oils tend to gum things up. Tri-Flo is also excellent if not sprayed. Dri-Slide manufactures a small, plastic applicator with a needlelike tip that is a great boon in bicycle maintenance. It puts the oil (one of the above or Dri Slide) only where you need it one drop at a time. There is no overspray, no mess, no fumbling to fit large applicators in tight spots. Ask for an applicator at the shop where Dri-Slide products are handled. This is the best method of carrying oil on tour we have found yet. It’s compact, light and does not leak (under $2). A light spray like WD-40 or LPS 1 is good for squeaky brake levers if you want to loosen the action without leaving a mess. Squirt a short spray inside the lever near the pivot bolt.

Once every six months to a year, depending on the type and amount of cycling you do, lubricate your brake cables unless you have Teflon-lined housings, which should not be lubricated. Loosen the nut on the pinch bolt to free the cable end, then strip it out of its housing. Clean the cable with a rag, then lubricate with grease, paraffin, oil or one of the special bicycle-lubrication products. If you use a spray, squirt into the housing also.

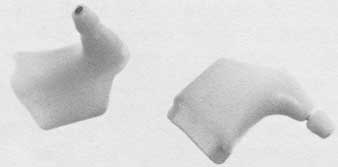

Gum-rubber brake hoods.

Brake (and derailleur) cables need replacing every two years or so depending on where you ride and how much. Look for broken wire strands and other signs of wear around the pinch bolts and where the cable enters and exits the housing. When you replace cables buy the best you can. Campagnolo, Elephant Brand, Wescon, Rixe, Schwinn and Sun Tour are some of the best. Don’t try to save a few cents with cheap, thin cables. Get thicker cables with a woven pattern instead of a simple twisting of wire strands. Near the ocean, stainless steel cables are a wise investment for protection from corrosion.

One last area of brake maintenance is caring for the gum-rubber brake hoods (covers) on your brake levers. You can add these yourself; they are stock on some bikes. These tend to get hard and stiff like your brake pads and eventually tear apart if not cared for. In tense sun and heavy air pollution also take their toll. The best protection is a product called Armor-All. Spray a little on a rag and work it into the brake hoods every month or so. It’s good also for the gum sidewalls of your tires but be careful to keep it off the rims.

Drive Line Maintenance

As a touring cyclist you should be competent in maintaining and repairing those areas where the chain has con tact: chainwheels, cogs, jockey (idler) wheels on the rear derailleur, and the chain itself. Keep the entire drive line as clean as possible to increase efficiency and prolong the life of the various components. The chain must be lubricated enough to keep friction to a minimum but not so much as to attract dirt.

Some cyclists go for months with out needing to lubricate their chains, others touring or riding 50-1 00 miles a day should lubricate their chains weekly. You know your chain needs attention when it talks back to you. If you hear even one squeak in one link, get out the oil. Riding in the rain assures the need for a lube job; as you gain experience you will know when to oil by the sound of the chain.

The right lubricating medium for chains is a topic of much interest and controversy in cycling circles. Everything from yak fat to paraffin and hot motor oil has its proponent. Until several years ago we used various spray chain-lube products developed for both bicycles and motorcycles, finally settling on LPS-3. They all did the job but picked up plenty of dust and dirt from the road. The whole idea is for the out side of the chain to be as clean and dry as possible while the inside rolling surfaces are lubricated enough to resist friction and wear.

We now use Dri-Slide, one of the wet-solution propellants that dries on contact leaving a film of molybdenum disulfide (graphite-like), highly resistant to friction and water penetration. There is no exterior coating to attract dirt. It’s available in both squirt cans and aero sol sprays; spraying is easier but some prefer to apply it drop by drop to each link of chain.

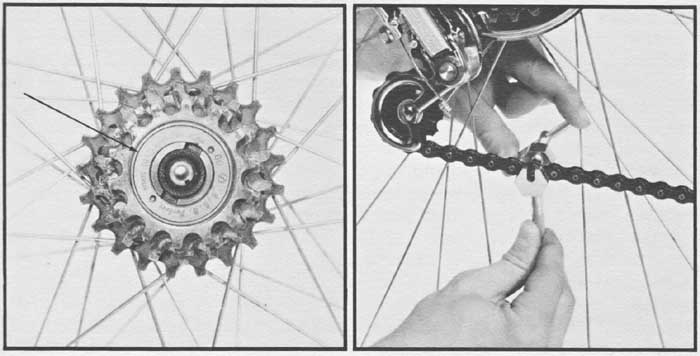

A variety of chain tools.

To keep your chain in top condition periodically remove, clean and lubricate it. You can do it now even if your bike is brand-new both for practice and to get started right. You will need a chain tool ($3-$7). On a derailleur bicycle there is no master link as on single-speed or 3- speed bikes. Use your chain tool to break apart any link. The Shimano Uniglide chain requires a special tool of its own. With your chain tool press any rivet until the chain can be separated at that point. Don’t press it all the way through or you will be sorry when you must link it back together again. Let it stay in the chain link’s outer plate as the inner pulls free. Your chain tool directions may specify how many turns it takes to perform this job; at any rate, practice so you know how far you can go. Press the rivet just far enough to barely hold the links together, then twist the links for final separation. If you are taking your chain off for the first time, make a drawing of how the chain laces through the jockey wheels in the rear derailleur. You’ll be glad you did.

Once the chain is off the bike, soak it in a clean solution of solvent. Once available in any amount at most gas stations, solvent now is hard to find in less than five-gallon cans. You can use paint thinner, some recommend kerosene (we find it leaves a greasy film), or — only as a last resort — white gas or automobile gasoline does the job. Be careful with gas; use it outside and away from any flame (including pilot lights on gas water heaters). If you can, put the chain in a small can with a cover and shake it around. As the solvent gets black, dump out the old, clean the can, and put in some fresh. Usually one change of solvent is enough, but repeat the process if necessary until the final rinse comes out clean. New chains re quire a good soaking to remove grease packed into them. When the chain is completely clean, take it out and hang it to dry. Vigorous shaking speeds up this process.

As you wait for your chain to dry, clean all the components over which it passes. It doesn’t do any good to put a clean chain on dirty components. With a rag pinch the encrusted grease and dirt from the sprockets on the jockey wheels, chainwheels and cogs. This takes time but is an alternative to taking each of these components off for individual soaking in solvent.

This is a good time to check the lubrication in your freewheel. Spin it. Does it sound gritty and sticky? How about the cogs? Are they reasonably clean or deeply encrusted with grease and dirt between them? If yes, you should service your freewheel as well but only if you are sure it needs it. To do this, remove it from the hub as outlined in the spoke failure section. Scrape off as much dirt as possible, then immerse it in a can of clean solvent. Use a small brush and a rag to clean between each cog. Change the solvent in the can when the worst of the dirt is off. Keep cleaning with new sol vent until the entire cluster is sparkling. When it’s spotless, soak it once more in clean solvent to remove any fine, inner grit from the freewheel. Spin it on your finger and listen for gritty sounds. Slosh it around in solvent until it spins smoothly without any telltale signs of grit. Remove it from the solvent for the last time, shake it and lay it down flat to dry, changing sides periodically.

When the freewheel is completely dry it can be lubricated. Any medium-weight oil will do or you can use Dri Slide. Spin the freewheel on your finger observing where the inner portion separates from the outer on both sides. Squirt oil in that separation while turning the freewheel until it begins to run out the other side. Wipe it off and spin again. Do the same on the other side. When finished, wipe it all again and grease the threads on the freewheel and hub with ordinary bicycle grease before screwing it back onto the wheel.

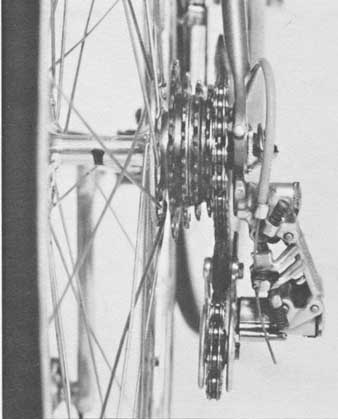

Chain tool in action with rivet almost driven out.

(left) The arrow shows point at which oil is inserted into freewheel

(front side); (right) Chain properly run through jockey wheel of rear

derailleur and chain tool pushing rivet back into place.

Freewheels commonly are a neglected part of the bicycle; apply oil whenever you have the wheel off or at least every 1,000 miles to insure long life. You should be able to oil the free- wheel without an extensive cleaning procedure unless there is a problem with the spin (grit inside). You don’t have to take the freewheel off the hub just to clean and oil it; only when it’s too dirty to clean with rag and brush.

By now your chain is dry and ready to lubricate. Hold the chain by one end and slowly spray down the top side; turn it over and repeat. With a clean rag, wipe all excess spray from the side plates leaving lubricant only on the in side between the bushings, rollers and rivets.

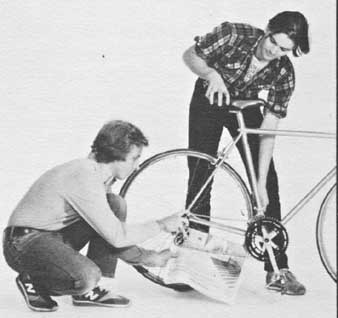

You can lubricate chain with spray (Dri-Slide) while it’s still

on bike, but you need some help.

One person should hold the bike and turn the crankarm slowly backward. The other should spray the chain and hold newspaper against the wheel to protect against spraying the rims.

At this point your entire drive line is free of grease and dirt. Thread the chain back on the bike and assemble the links. Remove the chain tool when the rivet is pushed in so that an equal amount shows on each side. Check the link for flexibility; if it’s stiff, hold the chain on either side of the sticky link and twist back and forth to loosen it.

With the drive line clean and free of excess oil we believe you will go many carefree miles before you need tend to it again. Periodic lubrication can be done with the chain on the bicycle. Have a friend hold the bike up while turning the crankarm slowly backward. You should insert a newspaper between the chain and the rear wheel to keep oil away from the rims. Spray a continuous stream of chain lube as the chain makes one revolution. Let it dry for a minute or two, then wipe excess oil from the out side of the chain. Make doubly sure there is no lubricant on the tire or its rim. If there is, don’t wipe it with the same rag you used on the chain. The rim must be cleaned with solvent. This shouldn’t be necessary if you’re careful.

Part of a periodic maintenance is cleaning off the jockey wheels and brushing dirt out of the cluster with a small, stiff bristle brush used for this sole purpose. Thanks to products like Dri-Slide the days of sticky, dirty chains are over.

Derailleurs

Derailleurs seldom break down by themselves, nor are they particularly difficult to adjust once properly set. Most derailleur problems are traceable to one of three situations: neglect, abuse or improper installation. We can’t go into derailleur installation and adjustment here; our purpose is to keep you on the road, not in your garage. Many books adequately cover this subject if you find yourself in need of more information along this line. Glenn’s Complete Bicycle Manual is probably the best single source.

If your derailleurs function properly to begin with, you are careful with them, and no accident befalls them on tour they should keep right on functioning well. But in the sometimes-not-so-ideal world of bicycle touring, small adjustments are occasionally needed. You should know what is necessary and how to do it. Because of the many derailleur types and designs, it’s impossible to be specific. Spend some time observing your particular derailleurs. See how they function in action either with the bike on a bike stand or hanging by a rope from your garage rafters or a tree so the rear wheel is off the ground. Check them out as you read the following, then, if you still have trouble, look in one of the many repair books available.

Rear Derailleurs Cable Adjustment

If the derailleur cable is too loose — if it can be pulled away from the frame a full inch or so with little pres sure while the shift lever is fully forward and the chain is on the smallest (high gear) cog — the cable tension must be adjusted. First, try screwing out the cable-adjusting barrel if your derailleur has one. If that does not correct the slack, screw the cable-adjusting barrel all the way in, loosen the nut that pinches the cable, and pull the cable tight with a pair of pliers. Pull firmly (but not too tight) then tighten the nut.

To Align Rear Derailleurs with Sprockets

Put the chain on the smallest cog and largest chainwheel (high gear). Be sure to rotate the crank when shifting gears. If the derailleur is not marked gear screws), look inside the derailleur mechanism to see which adjustment screw is touching or nearly touching its stop. This will be the high-gear adjustment screw. Adjust the screw (in or out) until the center line of the jockey wheels lines up with the center line of the smallest cog. It’s best to align the pulleys slightly inboard (toward the spokes), then adjust the screw while turning the crank to revolve the wheel, so the chain will jump onto the smallest sprocket from the next largest.

End view of rear derailleur jockey wheels (di with the letters

H and L (high- and low-directly under the small cog).

[left] Rear derailleur cable adjustment: Place wrench on rear derailleur

pinch bolt and pull cable tight with pliers. (The chain should be on

smallest cog.) [right] To align rear derailleur with sprocket,

adjust screw in or out until center line of the jockey wheel lines up with the

center line of the smallest cog.

Next, shift or put the chain on the largest cog and smallest chainwheel (low gear). Adjust the low-gear screw as before until the center line of the jockey wheels lines up with the center line of the large cog. Align the pulleys slightly outboard (away from the spokes), then gradually adjust the screw so the chain will just jump onto the largest sprocket from the next largest as the wheel turns.

To align front derailleur with chainwheels, place the wrench

on front derailleur pinch bolt while pulling cable firmly with pliers.

Front Derailleur Cable Adjustment

If the cable can be pulled away from the frame an inch or more with little effort while the cable is in its slack position, it must be tightened. Loosen the nut or screw that locks the cable in place. Pull the cable firmly with pliers (but not too tight); retighten the nut or screw.

Top view of inner side of front derailleur cage (1/16 inch from

chain) with chain on smallest chainwheel.

Top view of outer side of front derailleur cage (1/16 inch from

chain) with chain on largest chainwheel.

To Align Front Derailleur with Chainwheels

Place the chain on the large rear cog and the smallest chainwheel (low gear). Make sure the shifter lever is fully forward or back, whichever determines low gear on your particular derailleur. Turn the low-gear adjusting screw until the inner side of the derailleur chain guide (cage) clears the inner side of the chain by 1/16 inch and the chain does not rub when rotating the pedals.

Next, shift or put the chain on the largest chainwheel and the smallest cog (high gear). Turn the high-gear adjusting screw until the outer side of the front derailleur cage clears the outer side of the chain by 1/16 inch and the chain does not rub when rotating the pedals.

Emergency Repairs

No matter how excellent your preparation, there are going to be some emergency repairs that will tax your skills and certainly your tool kit. If you are caught without the proper tool or spare part, there are a few tricks that you might use to keep yourself on the road.

Broken Chain

With your chain tool, remove the defective link(s) and rejoin the chain. Don’t use your large chainwheel and cogs until you check to see if the rear derailleur will handle the shortened chain. If not, ride in higher (smaller) gears until you can get spare links. Better yet, carry some with you.

Broken Rear Derailleur

Manually put the chain on a mid range cog and shift only the front derailleur when needed. If the rear derailleur is totally mangled so that the jockey wheels won’t take up the slack, take the chain off the rear derailleur completely, put it on a middle cog, then shorten the chain until it’s tight. You now have a 1- speed to get you to a repair shop.

Broken Front Derailleur

Manually put the chain on the smaller chainwheel (unless you can handle the higher gears on relatively flat terrain). You now have a 5-speed using the rear derailleur alone.

Broken Brake Cable

This repair will work only if the break occurs near the lever and you have at least three inches of cable left beyond the pinch bolt at the other end for just such an emergency. Release the pinch bolt, pull the cable partway out and lace it through the shifter or brake lever. Tie a knot or two in the end, pull the cable back and tighten the pinch bolt. Better yet, always carry a spare — the longest cable that you might need.

Broken Critical Bolts

Spare bolts for your chainwheels or derailleurs can sometimes be found in your racks or fender dropout eyelets. Bits of wire picked up along the road can be used in these less-critical connections. On long tours carry spare, hard-to-find nuts and bolts. This is especially important for bar-end shifter parts since few shops stock spares for those. In some cases, you might end up having to buy an entire shifter set for the want of a simple nut or bolt. A 35 mm film can filled with carefully thought-out spare parts is invaluable on long tours.

Damaged Tire

The best remedy is carrying tire- casing booting in your repair kit. This is a cloth, sometimes rubberized, that is glued inside the tire to cover damaged areas and to protect the tube. Booting is available at better bike stores and is well worth getting ahead of time. In a pinch, use an old inner tube or a piece of heavy truck inner tube found along the highway. Glue it in with your patch-kit glue.

Foldable spare tires give less-than- perfect results; the one we tried was murder to mount on a 27 x 1 ¼-inch rim and prone to popping off, disturbing to say the least. A regular spare tire is easily carried folded in a figure eight (tri pled) about 11 inches in diameter. We wrap this with plastic for protection so it looks somewhat like a large donut. It can then be carried wherever convenient in baggage or tied onto the frame or fork with two extra toe straps. This has never damaged the tire and has saved us considerable grief at least once.

To protect and carry your clincher tire, fold it into a figure eight and a double circle about 11 inches in diameter.

Steve, the touring cyclist mentioned earlier, has been known to wrap friction tape around the whole tire and rim over the damaged area. In really harsh road conditions, he covers that with a layer of wire to protect the tape. If you must do this, don’t apply the brake on the patched wheel.

Ruined Rim Strip

It might be possible to do without one for a short time but it’s best to re place it with a spare or a strip of inner tubing, handlebar tape or adhesive tape from your first-aid kit. A spare rim strip doesn’t take up much room in your repair kit.

- - - - -

When you are able to perform the adjustments and repairs to your touring bike that we have covered so far, you will be qualified to handle about 80 percent of the trouble that can come your way on the road. You are in an excellent position as a touring cyclist if you are able to keep your own machine on the road without assistance.

There are, of course, many other maintenance procedures and repairs beyond what we have covered here. Many are as easy to master as fixing a flat, others require skill, experience and special tools. If you enjoy working on your own bicycle, there is no end to the pleasure it offers you. Tinkering with your bike can overcome weather-bound depression just as waxing your skis seems to make winter hurry along. If you become competent in the basic maintenance and repair procedures in this section, we think you will develop the self-confidence to tackle other, more complex areas with the help of manuals on the subject. Meanwhile you can tour long miles and feel confident in your ability to take care of yourself and your bicycle. That is what this guide is all about.