Your pedaling style is probably not optimized. You can also probably improve your cycling posture and breathing mechanics, to get more air into your lungs with each breath.

When folks think about their pedaling style, they usually think only about pulling with each foot through the upstroke. However, that approach ignores the fact that the vast majority of the power that a cyclist generates is on the downstroke. The major benefit of focusing on the upstroke is actually in releasing the pressure on the pedal just past the bottom of the stroke. If you do not unweight the pedal-before it starts coming back up, then you are working against yourself because your front foot is lifting your back foot effectively wasting some of your power.

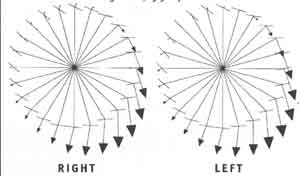

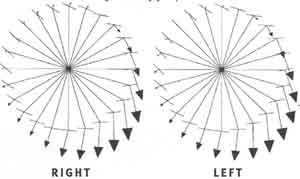

Another thing you should do is push down sooner. If you let your upward foot coast over the top and don't start pushing down until your reach the two- or three-o'clock position, you are leaving some of your potential power unused. Think of pedaling -- either sitting or standing -- as climbing a set of stairs. Focus on stepping up to each successive stair and stepping down onto it as soon as your foot gets on top of it. Doing so, you will naturally lift each foot off the bottom of the stroke and pull up on it, and you will apply power at the top of the stroke sooner. Diagrams 1 and 2 show how the feet of two riders differ in the magnitude and direction of force on the pedals at each position in the pedal stroke. Diagram 1 illustrates a more efficient pedaling style than Diagram 2; in Diagram 1, the cyclist's back foot resists the upward movement of the pedal on the upstroke less, and her forward foot begins pushing down at a higher position in the stroke.

Pedaling while standing up is generally inefficient, since it makes your center of mass move up and down, which requires energy, and it also increases your aerodynamic drag. However, there are times when standing saves energy in the long run, like when sprinting to reach a group of riders so you can draft among them, or when sprinting to carry your momentum over a steep, short hill. Furthermore, on a long climb, aerodynamic drag has a lesser effect due to the slow speed (air drag increases as the square of the velocity, so at half the speed, the rider has a quarter the drag), so the aerodynamic downside of standing is less. And if being out of the saddle is what it takes to generate enough power to stay with your group over the climb, after which drafting with them will save you energy, then so be it.

When you're standing, think of the stair analogy mentioned earlier. Put your entire weight on the pedal at the top of the stroke, rather than leaning on the bars or having any weight on the other foot that is coming up. Use your weight to push the pedal down while at the same time forcefully straightening your leg. If you get to the bottom of the stroke with a bent leg, you are again leaving some of your power unused on a shelf. And the act of lifting your downward foot up to the next stair takes your weight off the bottom pedal and pulls it up as well. When standing, use your arms to pull up on the bars, not to rest on them. This will also naturally bring your body into a position of balance over the pedals, so that your force and weight are directed straight down over the pedal, rather than having your butt back, which would require you to transfer power through your arched back.

Pedaling efficiency especially makes a difference when climbing, notably on dirt. When pedaling up a steep climb, your cadence is low -- an ideal condition in which to learn pedaling technique. Like learning to drive a manual transmission car or riding a bike for the first time, pedaling technique is best learned at low RPMs. Work up to higher RPMs, as you get better, keeping the same technique.

Above: Clock Diagram 1 (300 Watts; 99 RPM) The size and direction of the

arrows show the magnitude and direction of each foot's force on force-measuring

pedals at each position in the pedal stroke. Notice that this cyclist

works against herself less on the backstroke and begins the downstroke

earlier (higher in the stroke) than the cyclist in Diagram 2.

Above:

Clock Diagram 2 (250 Watts; 97 RPM) The size and direction

of the arrows in this diagram note a less-efficient pedaling style than

that shown in Diagram 1. This cyclist is pushing down with the back foot

longer than the other cyclist, and she begins pushing down with the forward

foot later.

You can also improve your breathing form. While cycling, notice if your chest is open or if your diaphragm and shoulders are impinging on your breathing cavity. Make a conscious and deliberate effort to open your chest. Breathing technique is also important, and besides being conscious about it, you can actively pursue disciplines like yoga and the "Alexander Technique" that focus on breathing.