PART V

American Frame Builders

With the exception of the Schwinn Bicycle Company, frame building is in its infancy in the United States. Most American builders have entered the profession within the last decade. With the exception of the European builders who emi grated to the United States (Colin Laing, who is English but builds in Phoenix, and Francisco Cuevas, who is Spanish but builds in New Jersey for Paris Sport), most are young. Few are over 30.

The Americans are considered technicians rather than artisans like the Europeans. Few European builders use lathes, mills, and jigs in the frame-building process. Because of American preoccupation with perfection, the American builder sometimes tends to over-file the frame to achieve flawless lugwork. Although he has far less experience than his European counterpart, the American builder compensates by being more innovative. Generally he will build any desired frame configuration and he does not limit himself to the use of only one kind of tubing. Instead, he finds use for Reynolds, Columbus, and Ishiwata tubing.

Finally, he is more tolerant of unusual requests such as 18-inch or 29-inch frames although some handling problems may result because of an untested or unsound design. Some of the less-experienced builders are so anxious to please their customers that they may construct a technically unsound frame.

The American frame builders will be a force to be reckoned with. Although the number of competent builders are few, their experience grows daily as the demand for their products increases.

Schwinn Bicycle Company

1856 North Kostner Avenue

Chicago, 1L 60639

When most Americans think of bicycles, they think of Schwinn. The Schwinn name has become synonymous with quality bicycles. Schwinn became a leader by providing expertly engineered bicycles backed by a generous manufacturing quality guarantee. People have claimed that Schwinn was the impetus behind the bicycle boom of the 1970s by promoting and introducing strong and reliable 10-speeds with stem shifters and dual brake levers. Whether this is true or not, Schwinn did bring the average customer from a 3-speed to a 10-speed model with little alteration in his cycling position.

Although this may not seem like a great feat the prevalent attitude that the "bent over" position was uncomfortable had to be changed, as well as the image of the bicycle as a toy. Once adults began riding their new 10-speeds, they realized that the "bent over" position was actually comfortable and more efficient than the upright position.

Arnold, Schwinn & Company was incorporated in 1895 by Adolph Arnold and Ignaz Schwinn. They were interested in manufacturing and selling bicycles and their parts. Arnold, Schwinn & Company was the brainchild of Ignaz Schwinn who had come to this country in 1891 and had become frustrated working for other bicycle companies. His whole life showed initiative and genius that had been unfulfilled working for others.

Ignaz Schwinn was born in 1860 in Baden, Germany. At a very early age, he became a machinist's apprentice and began working on the "invention of the age," the bicycle. Ignaz went from factory to factory trying to find a niche for himself. Frustrated, he began designing bicycles on his own while working at various machine shops. His design of an improved safety bicycle interested Heinrich Kleyer, a small builder of high-wheeled bicycles. Subsequently, Kleyer hired Ignaz Schwinn as a designer and factory manager. The Kleyer factory started producing some of the first safety bicycles in Germany. Although the Kleyer factory prospered, Ignaz Schwinn was still not satisfied.

Background When he was 31, Ignaz Schwinn emigrated to Chicago. In Chicago, as in Germany, Ignaz worked in a number of factories designing bicycles. But Schwinn was not content; he wanted to build bikes for himself. By 1894 Ignaz Schwinn had met Adolph Arnold who was the president of Arnold Brothers, a meat-packing establishment, and president of the Haymarket Produce Bank. Adolph Arnold had faith in the genius of Ignaz and provided him with the financial backing necessary to start a bicycle factory.

A building was rented on the corner of Lake and Peoria streets. Ignaz Schwinn designed the bicycles and the tools to make them, purchased the machinery and equipment, and hired the personnel needed to operate the factory. Schwinn began operation of his factory in 1895 at the height of the bicycle boom.

When he started production, there were probably 300 other bicycle factories and as many assembly shops already operating in the United States. In spite of the many manufacturers, nobody was able to produce enough bicycles to satisfy demand. However, like most trends, the bicycle boom died by 1899 and most of the bicycle manufacturers closed their doors. The bicycle racing stars of the 1890s, who were some of the best riders in the world, quickly faded, leaving their European counterparts the task of developing racing bicycles and equipment. As the United States slipped into the middle ages in bicycle activity, Europe experienced its renaissance.

Although Ignaz Schwinn had to cut back on production, his sound management and good product line allowed him to remain profitable. In 1908 Ignaz Schwinn bought out his partner Adolph Arnold and thus became the sole owner of Arnold, Schwinn & Co.

The name remained unchanged until 1967 when it became the Schwinn Bicycle Company.

Unlike many bicycle manufacturers, Schwinn has always been interested in further expanding its markets. But to educate an apathetic U.S. population in the 1920s was no easy task! Schwinn started a full-scale marketing campaign to encourage the sale and use of bicycles. Historians might well claim that Schwinn brought the American bicycle business out of the depression and into a recovery period by introducing balloon tires, front-wheel expander brakes operated by a hand lever on the handlebars, a drop-forged handlebar stem, a full-floating saddle and seatpost, knee-action spring fork, and other design features.

Schwinn's eagerness to promote bicycling activities began in the 1890s with the support of a racing team known as the world team, which exposed thousands of fans to the excitement of racing. When the track at Garfield Park in Chicago opened on October 3, 1896, twenty-five thousand people watched Jimmy Michael, a star rider for the world team, break the American five-mile record! Another spurt of enthusiasm came in the 1930s when six-day racing, which originated in Madison Square Garden during the depression, became popular. At the time, most riders were using European-built bicycles and components because the previous decline in bicycle sales had forced all the American companies to cut back production. There were, however, a few small custom builders in this country such as Wastyn and Drysdale who were still building racing bicycles.

Emil Wastyn had a small frame-building shop in Chicago, located not far from the Schwinn factory. Ignaz Schwinn, being eager to promote cycling, hired Emil Wastyn on a consulting basis to help him design a quality American bicycle suitable for six-day racing. The result was the Paramount track bicycle built with Accles and Pollack (an English tubing company) double-butted tubing, English cast lugs, and specially designed and built Schwinn hubs and cranks. As soon as the Paramount track bicycle went on the market, American riders demanded the bike.

To help promote cycling, Ignaz Schwinn again sponsored a racing team. This time, the team was called the Schwinn Paramount racing team. Some of the best six-day riders in the United States, including Jerry Rodman and Jimmy Walthour were on the Schwinn team. Although there was much enthusiasm for six-day races in the 1930s, this enthusiasm waned with the onset of World War II and never recovered. After the war, Americans were too busy buying refrigerators, washing machines, and auto- mobiles to pay much attention to bicycles and bicycle racing.

The most recent demonstration of Schwinn's continued sup port for bicycle racing came in 1974 when the Amateur Bicycle League (now the United States Cycling Federation), the governing body of amateur U.S. cycling at the time, allowed sponsorship of amateur riders. Schwinn presently provides sponsorship for five different amateur racing clubs across the country, one of which is the Wolverines (now called the Wolverine-Schwinn Sports Club) which has provided Schwinn with champions such as Sheila Young, Sue Novara, and Roger Young, all of whom ride Schwinn Paramounts. (Before the sponsorship, Sheila Young rode a Cinelli track bicycle and Sue Novara rode a Pogliaghi.) Building Philosophy When Schwinn began building its standard-line Paramount bicycles in the 1950s, Nervex lugs were used. Twenty years later, Schwinn is still building the Paramounts with Nervex lugs. In the 1950s, the Nervex lug was the most popular design as well as a quality product. Today, the fashion is the smooth, simple Italian-type lug. As a result, Schwinn has been seriously thinking about changing. Like other changes that Schwinn makes, how ever, it has to be carefully researched and developed. Schwinn is interested in more than the overall finish of the lug. They are primarily concerned with accuracy of internal diameters, maintenance of the angles, and the quality of the threading and facing of the bottom brackets.

Schwinn used cast lugs in the 1930s when the first six-day frames were made but the lugs were sand castings, which resulted in rough, pitted finishes. The casting process has been greatly improved since then and Schwinn is presently looking at some investment cast lugs, bottom brackets, and fork crowns only because the castings are able to achieve fine definition that requires less hand finishing.

Various fork crowns are used on the Paramount’s: on the road, a pressed steel Nervex crown; on the track, a forged Japanese crown; and on the tandem, a specially machined crown out of a solid block of steel. Although Schwinn is considering using cast fork crowns on the Paramount’s, they believe that it is not necessary since the weakest part of the fork is the blades. If engineering were the only consideration, Brilando would probably use a heavier-gauge fork blade than a cast fork since he believes "an ideally designed fork should give uniformly throughout." Most of the forks that Schwinn uses are pre-raked at Reynolds to Schwinn's specifications. Schwinn furnishes Reynolds with a drawing indicating the exact dimensions needed. The fork rakes currently used are:

1. 1 3/8 inches on the track frames;

2. 1.75 inches on the road frames;

3. 1.5 inches on the criterium frames.

Interestingly, 1 3/4-inch fork rakes are used on both the touring and the road racing models. Until recently, the touring bicycles used a 2-inch fork rake but laboratory tests confirmed that 0.25 inch less gave the tourist a more stable and safer ride.

Schwinn was probably one of the first builders to use the large 5/8-inch stays on their standard frames. According to Brilando, with 5/8-inch seatstays "you can get greater lightness as well as stiffness by using a lighter-gauge tube." The Paramount’s incorporate a seatstay attachment that is chamfered with small pieces of metal used to cap the seatstays.

Other seatstay clusters have been considered but all were rejected on the belief that there is no advantage of adding extra weight in this area by using top eyes or wraparounds, which require heavy fixtures to give their neat appearance. Schwinn's analysis found that some of the so-called lightweight fastback stays use a heavy piece of metal built into the lug to allow an adequate brazing surface. As Frank Brilando sees it, "People try and save weight in the tubing and they add weight on the seat lug! That doesn't make sense. I would rather see that weight put into the tubing to give you overall frame stiffness than something just for cosmetics." All Paramount’s (road, track, tandem, custom) are built on jigs. There are only two brazers, Lucille and Wanda, who work on the Paramount’s. They are probably the only women in the industry who braze top-quality frames! Lucille and Wanda have been brazing Paramount’s for more than 25 years and they do an extraordinary job using a small flame and the lowest possible temperature. They have learned to control the torch to keep the tubes as cool as possible during the brazing process to maintain the tube's physical properties. Silver solder is used for braze primarily to minimize overheating the tubing. With the lower temperature required to braze with the silver, it is possible to rigidly hold the frame in a jig and expect minimal distortion in the frame. "If a braze with a higher melting point was used and everything was jigged and held rigidly, there would be no room for expansion of parts," Brilando claims. "With our system of jigging and use of silver solder, we keep everything very much in line." The entire frame is silver-soldered except the dropouts. On these, brass is used because the fits are not as good; there is generally more than .003 inch of space that has to be filled.

Figure 17-1: Ferenc Makos, at an aligning table, makes sure the Paramount

frame is perfectly aligned and straight.

The tandems present another problem. They are also built in rigidly held jigs, but they are bronze-welded (fillet-brazed) be cause they do not have lugs. Of course, there would be much distortion if the tubing were lightweight but with the use of ...

Figure 17-2: Schwinn is the only company we visited that exclusively uses

women to handle all brazing. Here Lucille Redman works on a Paramount frame

as she has done for around 30 years.

... heavier straight gauge tubing, the expansion and contraction of the tubing is minimized.

Working together with the two brazers are two other frame builders who perform the actual assembling of frames. They work from specifications; cut, miter, and flux all the tubes; and accurately assemble the entire frame in the jig. After the setup is complete, the frame is brazed by either Lucille or Wanda. The majority of the tubes for the standard Paramounts are mitered on a special milling lathe. However, on the custom frames, the majority are hand-mitered because it is faster and easier to hand-miter than it is to reset the lathe.

If any one aspect of the building process was singled out as the most important, Frank Brilando believes he would have to choose the brazing process.

The brazing is more important than the mitering.

Still, I don't know how you can separate them. You can have a poorly mitered tube and a good braze job and nobody would know the difference provided you've got a rigid lug because the body of the lug is so much greater than the tube that you'll never see. Any failures will always go beyond the lug on the tube. If you have a good sturdy lug, the fitting of the tubes isn't going to be that critical. I think that a lot is overemphasized be cause the joint of the tube is so minimal compared to the strength of a lug. If you have very thin lugs, then I would say that the mitering becomes very important.

Frank believes that unless someone has a lot of experience brazing, it is easy to be fooled into thinking that you have a good joint, because it is difficult to know whether the braze has gone all the way into the joint. There are many things that Frank believes are important: proper preparation of the joint, cleaning it properly, fitting up the joint, getting the right heat to sweat-in the braze; but these are all things that you cannot see by looking at the frame. Consequently, the reputation of the builder becomes the primary guide to whether you have a good frame or not.

After the frames are built, they are checked for alignment.

Even with the careful precision with which Schwinn builds its Paramount’s, there can be a small amount of warpage that occurs in the hangar bracket. In order to realign the frame, the bottom bracket is re-tapped. The outer face of the bottom bracket is then faced off, after which a precision cone and Jock-nut is screwed into the bottom bracket. This cone and locknut fits on a fixed mandrel on a precision aligning table. The frame is aligned (cold set) to the threads themselves in the bottom bracket.

Schwinn uses a process similar to sandblasting, called glass beading, to clean the frame and prepare it for painting. It resembles sandblasting except that it uses a much finer material which is less likely to score the frame. The Paramount frames are painted with the standard Schwinn paint used on the other Schwinn production frames. The only difference is that the Paramount’s are all hand-sprayed whereas the production frames are done electrostatically. The translucent finishes receive a primer, silver, and final coat. The opaque finishes receive only a primer and topcoat.

When a custom order is received, it is sent to the product design area where Charles "Spike" Shannon, Paramount de signer, reviews it and lays out the dimensions on the drafting board to make sure that there are no design problems. If there is a problem, Spike will work with the customer, resolving any difficulties. There have been times, of course, when he has been unable to convince the customer and has refused an order because he thought it was unsound. Schwinn has the ability to give the customer exactly what he wants. The wait for a custom order can vary from one to four months depending on the time of year.

Custom tandem orders do not take any longer since all custom orders go right into rotation as they are received.

Schwinn's Paramount production is very small. Out of one million Schwinn frames that are built each year, only 800 are Paramount’s. The majority of Schwinn’s manufactured are the lugless, flash-welded models (which, in fact, are not lugless at all, because they have a head lug and bottom bracket lug that are flash-welded together). As required by the flash-welding process, heavier-walled welded tubing is used. Consequently, these bicycles are durable but heavy.

A number of Schwinn models have also been built in Japan to Schwinn's specifications. These bicycles have been the production lugged frame models which Schwinn was not equipped to produce when their popularity skyrocketed with the bicycle boom in 1973. Since that time, Schwinn has been working on setting up production for lugged frames. Soon, Schwinn will be producing production-line lugged frames in its factory in Chicago. This will mean that once again all Schwinn bicycles will be made in the United States.

Figure 17-3: Charles Shannon, engineer, checking wheel clearance on a

custom bicycle design.

Frame Selection

During the 1950s, Schwinn started building road racing Paramounts and, like the track bicycles, they were only built on a custom basis. Schwinn miscalculated the popularity of the Paramounts because when the demand increased in the 1950s, Schwinn was not equipped to handle it and had to hire Oscar Wastyn, Sr., to help build some of the Paramounts. Oscar learned how to build bicycles from his father (Emil) and took over his father's small bicycle store and frame-building shop which is still located near the Schwinn factory today. Now the store is operated by the third generation of cycling Wastyns, Oscar Wastyn, Jr.

With the many custom orders Schwinn was getting for the road Paramount, it was time to incorporate the Paramount into the standard Schwinn line. By 1956, all the bicycles supplied to the U.S. Olympic Cycling Team were built by Schwinn using Reynolds 531DB tubing and Campagnolo equipment. (Schwinn had used Accles and Pollack tubing before World War II, but it was not available in the 1950s.) Schwinn had conducted years of research and testing and by 1956 concluded that the best racing materials were made by TI Reynolds and Campagnolo. To this day, most of the Paramounts are still being built with Reynolds 531DB tubing and equipped with Campagnolo components.

In 1958, the Paramount road bicycle became a standard model in the Schwinn line. The standard Paramount was designed to fit the size requirements of 99 percent of the population. For riders with specific requirements, Schwinn has continued to build custom Paramounts for road or track use.

When the Paramount road-racing model first became part of the Schwinn standard line, it did not reflect the designs of the ordinary racing bicycle. Schwinn was one of the first builders to use steep angles on road bicycles. (In the 1950s, all road bicycles had much shallower angles.) Schwinn believed that since the American roads were so smooth, a road bicycle should be designed more along track lines for better, more responsive handling.

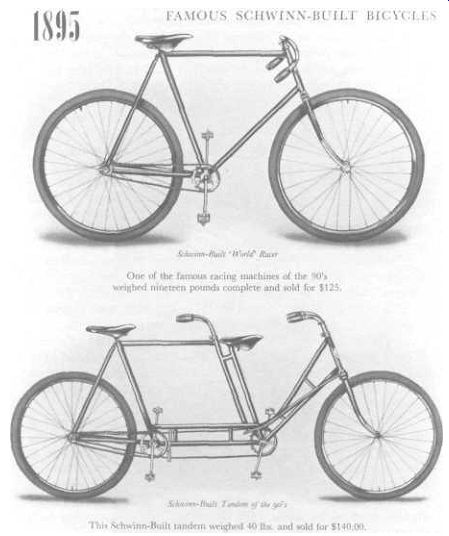

Figure 17-4: The relatively small degree of change in bicycle frame design

becomes immediately obvious when we compare yesterday's bicycles with today's.

Frank Brilando, vice-president in charge of engineering, has been with Schwinn since 1951. His credentials are extensive, including a berth on the 1948 and 1952 U.S. Olympic teams. He believes that Schwinn can satisfy almost every taste and need. If the needs are not met in the standard line, a special custom design can be provided.

Like Cinelli, Schwinn's building and design philosophy stresses rigidity over extreme lightness. For example, since it is difficult to build a good, stiff frame in a large size, Schwinn uses heavier-gauge tubing to achieve stiffness as the size of the frame increases. Extra-heavy chainstays and fork blades are used on all models. On extremely large frames (in excess of 26 inches), straight gauge SAE 4130 chrome molybdenum is used for the down tube and the seat tube. By combining this tubing with a stiffer front fork, Schwinn has been able to overcome a lot of the tracking problems that occur on large frames when riding down hill and riding without hands. Through years of experience Schwinn has opted for rigidity rather than lightness.

Frank Brilando doesn't believe that there's a great difference between the chrome molybdenum tubing and the Reynolds manganese-molybdenum tubing as far as the end product is concerned. He does believe that a little more caution has to be used when working with chrome molybdenum tubings because overheating and rapid cooling will cause more brittleness in the frame joints than with manganese molybdenum. Why does Schwinn use chrome molybdenum tubing more extensively? According to Brilando, "We've found the Reynolds tubing to be very good and there's no reason to change just for the sake of changing. Furthermore, 531 has good acceptance by the public." Frank Brilando believes that you cannot consider the top tube dimensions by themselves since they are influenced by the other frame specifications. As a rule, top tube length should not be a controlling factor in ordering a custom frame because if, for example, a shallow seat angle is requested (and everything else is constant) a longer top tube will be required. "Top tube length by itself doesn't mean an awful lot unless you tie it into the complete bicycle." Schwinn is probably the only large manufacturer in the world that makes a top-line touring model. The design of Schwinn's standard line touring model has been tested and retested to insure a safe and comfortable ride. The touring Paramount has a slightly longer wheelbase, due to a longer rear triangle, which distributes the weight of the rider and the touring load more evenly on the frame. Through testing, Schwinn has found that a slightly longer rear end (3/8 inch) will transfer some of the weight to the front of the bicycle and the better weight distribution will contribute greatly to the safety of the rider. If you know that the 3/8-inch longer stay gives you better weight distribution, what would happen if the rear triangle were lengthened by an additional 5/8 inch? Schwinn's tests have shown that a longer rear triangle will create instability and make the bicycle handling unwieldy. The 3/8-inch longer stay that Schwinn uses is the best compromise.

One of the greatest problems a tourist has to face is riding downhill with the weight of touring packs on the bicycle. Again, Schwinn has performed tests which indicate that the racer shares the problem of instability on downhills, but that his problem is more manageable because he is riding without bulky packs. The downhill problem is exacerbated when carriers and packs are attached to the bicycle, especially, as Brilando notes, "when rear carriers are not anchored solidly. They tend to shimmy and this transfers through the whole bicycle." To help eliminate this dangerous situation, Schwinn's testing has confirmed that:

1. carriers must be solidly secured to the frame;

2. carriers must be strong enough to support the packs;

3. the packs must securely fasten to the carrier, to insure as little movement as possible;

4. the weight should be distributed in the panniers with the heavy items at the bottom.

If you are going to use front panniers, the same criteria apply. Of course, overloading front panniers will cause a dangerously unstable condition. Although most people seem to be using front handlebar packs, Schwinn has not done any conclusive testing in this area, but Brilando believes "if it is rigidly held, it is not too bad. If it slops around, then you get into instability problems." The road racing Paramount that Schwinn offers in its standard line is designed for long-distance road races. A special lighter criterium frame is offered but only as a custom order. The same applies to the track frame. The standard Paramount track frame is built for sprints while lighter pursuit frames can be ordered on a custom basis. Although Schwinn uses Reynolds 531DB on all its frames, the tube gauges are heavier than the standard-packaged Reynolds 531DB sets. The reason for the heavier tubing is the belief that frame rigidity is affected more by the tubing than by the lug. Since frame rigidity is the basis of Schwinn's design philosophy, the necessity for thicker-gauge tubing becomes essential. According to Brilando, "Lightness is great for certain specific applications but generally for most usage, we tend toward the stiff side. We have built extra-light bicycles for pursuit and time trialing and so forth, but you have to apply the bicycle to the type of usage." On the standard track, road racing, and road touring Paramounts, the top tube is 18/21 gauge, the down tube 19/22, the seat tube 21/24, the chainstays are 18/20, and the fork blades 17/20.

When building special pursuit and criterium frames, special lightweight tubing is used, producing frames 1.5 to 2 pounds lighter than standard frames. Although lighter Reynolds tubing is used on many of the custom bicycles, Schwinn does use Colum bus and Ishiwata tubing as well. The Ishiwata tubing is called for when light specialty frames are required.

Like most respected master builders, Schwinn takes a conservative approach to frame building, emphasizing strength over lightness. Although the Paramount lacks some of the glamour and mystique of the foreign bicycles, it is superbly built and priced competitively. Most important, the generous warranty provides free frame repairs if a failure is due to faulty materials or workmanship.