Which bicycle should you buy? Certainly you should not rush out and buy just

any bicycle. Yet most beginners are bewildered by the hundreds of bike models

and their state-of-the-art components.

To avoid the confusion, you must first

understand the basics. And the initial step is to learn the names of all the

principal parts of a bicycle.

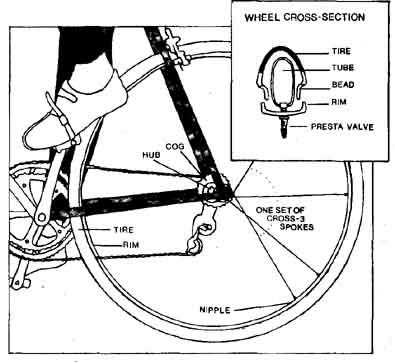

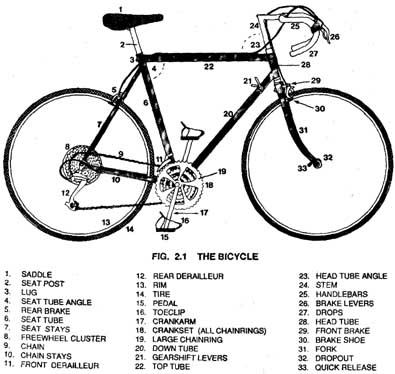

So study Figure 2.1 and familiarize yourself with bicycle terminology.

Begin

to talk about a saddle instead of a seat. After that, read on to the end of

section 5. Even though it sounds a bit technical, and you may not understand

it all the first time, try and grasp as many terms as possible.

Then go to a bike shop and identify all the parts you know the names of. Squeeze some brake levers and watch the brakes snap into action. Have a salesperson place a bicycle on a stand and allow you to spin the pedals while you move both front and rear derailleur levers through their full ranges of gear positions. Study how the derailleurs work.

Then ask the salesperson to release the front brake and to flip the front wheel quick-release lever. In just a few seconds the front wheel can be released from the bike. Ask the salesperson to show you the dropout slots in which the front wheel axle rests. If the salesperson isn’t busy, ask him or her to remove the rear wheel also. Study how the brakes are released and examine the rear-wheel dropouts. (Dropouts are the U-shaped slots into which the axles fit.) Take a good look at every part of the bicycle including the freewheel and cogs, chainrings, pedals, hubs, spokes, rims, and tires. (The freewheel is the cluster of toothed gears near the rear axle. Each individual toothed gear of the freewheel s called a cog chainrings also called chainwheels, are the toothed gears near the pedals.)

Along the way you’ll discover that bicyclists frequently talk about sets as in headsets, framesets, wheelsets, tubesets, brakesets, and cranksets. Componentry refers to all the components — like handlebars, crankset, brakes, stem, and seat post— that are added to the frame to make it a bicycle.

Adult bicycles fall into two main classes: road bicycles (formerly called “10 speed”); and all-terrain or mountain bicycles. Each class gives you a choice of three types:

Road Bicycles |

All-Terrain or Mountain Bicycles |

Racing bicycle or road racer Sports bicycle Touring bicycle |

Mountain racing bicycle Mountain bicycle City bicycle |

Differences between these types are often quite subtle. Some makers have also produced hybrids such as a sports-touring model. How ever, each type of bicycle is designed and built to excel at a certain function. A road racer is built for speed while a touring bicycle is designed for extended long-distance travel while carrying a load.

To buy the right kind of bicycle you must first know what you will use the bike for. No single bike can do it all. You won’t stand much chance of winning a road race if you ride a mountain bike, while a road racer is useless on a mountain trail. Thus you choose a bicycle for the type of riding you will do.

The snag is that most beginners don’t know enough about bicycling to decide exactly what type of riding they want to do. Nor do they know how far they will go into bicycling. Most start out wanting to ride for fitness but few know whether they’ll ever graduate to competition, whether they’ll ride with a club, or take an extended tour, or become an off-road enthusiast, or ride to work. Most newcomers also hesitate to lay out several hundred dollars for a high-performance bicycle in which they may lose interest later on.

You can make a much better guess at the type of riding you will do if you know more about what bicycles are capable of doing, the components they are built of, and the types of bicycles best suited to adults.

Let’s begin, then, by learning something about the frame and components that comprise a modern high-performance bicycle.

The Frame

Although a bicycle frame appears deceptively simple, the combination of design, geometry, and materials can make an enormous difference in performance, handling, and rider comfort.

On most medium-quality bicycles the frame consists of eight pieces of steel alloy tubing (called a tubeset) joined together by steel sleeves called lugs. Among the most popular alloys are chrome molybdenum (chromoly) and chrome magnesium. Most quality bicycles carry a decal identifying the type of alloy and the tube manufacturer’s name, which is commonly Reynolds, Columbus, Champion, Vitus, Tange, etc. The decal may also indicate whether or not the tubes are butted. For example, it may say, “Guaranteed made with Reynolds 531 butted tubes, forks, and stays,” or a decal on a mountain bike might be worded, “True temper chrome-moly triple butted.”

Butting means that tubes are tapered thinner in the middle and thicker at the ends where they enter the lugs. Tubes can be double, triple, or quadruple butted, indicating increasing levels of thickness at the tube ends. For it is at the ends, where the tubes enter the lugs, that the greatest stress occurs.

Top-quality lugs, such as investment-case lugs, reinforce frame joints and minimize weakening of the tube caused by the heat of brazing (a type of soldering) during construction. Other top-quality lugs often have decorative designs that permit superior brazing at lower temperatures. These top-grade lugs distribute stress over a wider area at the joint than do cheaper lugs. To eliminate brazing altogether, many frames today are built of lugless tubing.

With or without lugs, almost all medium-priced bicycles have frames of dependably good quality. Using chromoly and other steel alloys, manufacturers are producing rigid frames that are uniformly strong and easily repaired. Butted frames are lighter and provide a livelier ride. With their smart new graphics and custom dual-tone finish, these frames are often striking in appearance and design.

The Best Frame Materials

At present I recommend steel alloy as the best frame material for an entry-level bicycle. More expensive frames are available built of aluminum, titanium, and carbon fiber composites. But these have their minuses as well as their pluses. Frames of reinforced aluminum alloys are stronger than steel and dampen road shock well, but they can be costly to buy and expensive to repair. Nonetheless, aluminum frames — many with wide-diameter tubing — are becoming increasingly popular among advanced riders.

Titanium is also rigid, strong, light, and non-corrosive but relatively few titanium frames are available and the majority are quite expensive

For the frame of the future, carbon and other nonmetallic fibers bonded with epoxy appear to be the most likely replacement for steel. Their great stiffness, superior strength, light weight, good shock absorption, and non-corrosive qualities make them an innovative new frame material. Within the life of this edition it is quite conceivable that composite fiber may replace steel as the material of choice for medium-quality frames.

Carbon and other fibers are used in one of two ways: they are either made into tubes for conventional frame building; or they are molded into a single frame unit. A single unit allows futuristic- looking, aerodynamically designed frames that are smooth and rounded to minimize wind resistance. Because it is particularly good for damping road shock, polyethylene fiber is frequently used for the rear wheel stays through which most vibration is transmitted.

The type of frame shown in Figure 2.1 consists of two triangles and is called a diamond frame. Note the location of the head tube and seat tube angles. Variations in these frame angles of only one or two degrees can make a tremendous difference in comfort, efficiency, and responsiveness.

Changing frame angles requires corresponding adjustments in the length of the chainstays. And the overall geometry is further balanced by adjusting the rake, or curvature, of the fork blades. Thus we have two extremes: slack and tight geometry.

Frames with Slack Geometry

These frames have a slack head-tube angle of 70—72° and an equally shallow seat-tube angle of 72—74°. This makes for longer chainstays and a greater fork rake. In turn, this creates a longer wheelbase of 40—42¼”. (Wheelbase is the distance between the front and rear axles.)

A frame with slack geometry means that it scores low on speed and handling agility but that it offers superb riding comfort and exceptional stability, especially when carrying a load at moderate speeds. These qualities are prized for touring and mountain bicycles.

Thus we find that mountain bicycles tend to have head angles of 70-71°, a seat angle of around 73°, and a wheelbase of 41—42 1/2” or more. Touring bicycles typically have a head angle of 71-72°, a seat angle of 71-74°, and a wheelbase of 40-42 14”. Many experts suggest that a beginner buy a mountain bike with chainstays at least 17” in length and with a wheelbase of at least 42”.

Frames with Tight or Aggressive Geometry

These frames have a tight head-tube angle of 73—75° and a correspondingly steep seat-tube angle of 73-76°. Such high angles make for shorter chainstays, a steeper fork rake, and a short wheelbase.

This translates into superior control over a range of conditions important to racers such as delivering more power to the road, quick acceleration, fast cornering, stability at high speed, and nimble, responsive steering. These qualities are prized by racers, and the modern trend is to design racing bikes with increasingly steep geometry. Thus we find that the road racer typically has a wheel base of 38—39½”.

Steeper frame angles are prized by racers because they result in a stiffer frame. The more rigid a frame, the less it flexes with each downstroke of the pedals. Thus less energy is wasted in flexing and more net energy is transmitted to the road. However, a very stiff frame can be uncomfortable for extended riding, which is why touring and mountain bicycles are designed with a more flexible frame and a longer wheelbase.

Midway between these extremes is the sports bicycle. Its head- and seat-tube angles typically range around 73° with a wheelbase of 39½ - 40”.

Frame Size Explained

At this point I should note that frames come in different sizes to fit riders of different heights. Frame size is calculated by measuring the distance between the center of the crankset spindle and the highest extremity of the seat tube.

Road bicycles come in stock sizes of 19” (48 cm), 21” (53 cm), 23” (59 cm), 24 ½ (63 cm), and 25 ½” (65 cm). Some makers produce intervening sizes, while a few also make an oversized stock frame of 27” (69 cm). Mountain bicycle frames are smaller and usually come in sizes of 16½” -18”, 20”, 22”, and 24”, while women’s mountain bikes customarily have 18” or 19” frames.

Forks, too, must be geometrically matched to the frame. Standard on all modern bicycles is the unicrown type fork, a crownless fork brazed directly to the steering tube. While the unicrown fork helps deaden road shock, mountain bicycles also have large- diameter fork blades and a clearly visible rake. Together, these features provide exceptional shock absorption. At present, most composite-fiber bicycles use metal forks.

A good indication of a quality frame is that in smaller frame sizes, as the length of the seat tube is reduced, the length of the top tube is reduced in proportion. This makes for slight variations in frame angles of smaller frame sizes.

You won’t need to carry a protractor to measure frame angles. All specifications are quoted in the owner’s manual and in the sales literature that accompanies each model. Thus to ascertain frame angles, or chainstay or wheelbase length, you need only consult the model’s specifications. Comparison shopping for a bicycle is made much easier by purchasing a copy of Bicycling magazine’s Annual Buyer’s Guide, usually on sale for about $3 or available free when you subscribe to Bicycling. It gives full specifications on 300 different models.

Tip-offs to Quality

Other guides to frame quality are these. The overall weight of a typical racing bike is 19½ -23 pounds, a sports bicycle 24—26 pounds, a touring bicycle 25-30 pounds, and a mountain bicycle 25-31 pounds. All other things being equal, the lower the weight the higher the quality.

Another indication of quality is that all better frames have thick forged dropouts brazed onto the frame. Vertical rather than angled rear dropouts are now preferred.

Touring and mountain bicycles should also be well supplied with components brazed on for all accessories. Both front and rear drop outs should have two sets of eyelets for attaching touring racks and mudguards. All these frames should have brazed-on cantilever brake bosses. (A boss is essentially a small, round piece of steel brazed onto the frame into which a bolt may be screwed.) If you buy a French-made frame, make sure it has English threads.

A quality bicycle will have all bearings sealed. Inexpensive bikes have non-sealed bearings, which means loose ball bearings are rotating against a tapered cone, a setup that requires frequent lubrication and periodic adjustment. By comparison, sealed bearings are shielded to keep lubrication in and dirt and water out. Bearings and ball races are contained in a single unit that can be replaced inexpensively when it wears out. You should certainly expect all major bearing sets to be sealed.

Also not recommended for beginners are folding or recumbent bikes. I say this in all awareness that the concept of a folding bicycle appeals to many. However, most folding bicycles cannot compare in performance with rigid-frame models, especially those with smaller wheels. However, if you are considering a folding bike, the Moulton series (small wheels) and the Montagu bikes (full-sized wheels) are worth investigating.

One attraction of recumbent bicycles is that you can sit on a wide seat instead of a narrow saddle. But these bicycles seem slow on hills, and even veteran bicyclists have difficulty adjusting to them.

Fig 27 The wide seat is one attraction of recumbent bicycles. However,

many cyclists find them slow on hills.

The Wheels

The lighter and more responsive your wheels, rims, and tires, the easier your bicycle will be to pedal and the faster it will go.

Bicycle wheels and tires come in three principal sizes, namely, in 26” and 27” diameters and in the 700 size, which has a diameter of about 26.7”. Wheels of 26” diameter are used almost exclusively on mountain bicycles; 27” wheels are used for sports and touring bikes; and 700 wheels, originally for racing bikes, are used nowadays also for most sports and some touring bikes.

Almost all tires in use today are clinchers, meaning they have a cross section like an automobile tire, and they are always used with an inner tube. Formerly most racers used tubular tires, a very light tire with a self-contained inner tube sewn up inside it. Today, however, clincher tires are available in such light weights that the advantage of tubular tires is rapidly fading. Tubulars are expensive, Unsuited for touring, easily punctured, difficult to repair, and should be studiously avoided by the beginning adult. The best clincher tires have Kevlar beads and a belt of puncture-resistant Kevlar under the tread.

Inner tubes come in the same sizes as do tires. Two types of valves are used:

• Presta, or needle or French, valves are fairly standard on all better-quality road bikes. They are made of metal and will hold a higher pressure than Schrader valves. To inflate, unscrew the top of the valve and briefly depress it before inflating.

• Schrader valves are the same as those used on cars. They are fairly common on mountain bikes, although Presta valves are also available on 26” tubes.

If you have any choice, always take Presta valves. Most tubes are of butyl and require inflating about once a week. Other tubes are made of polytex compounds. Bicycle tires should never be inflated at gas stations. Gas station pumps deliver large amounts of air designed to swiftly fill an automobile tire. Such a huge air flow can easily burst a diminutive bicycle tube.

Instead, you should carry a frame pump on your bicycle to fit the type of valve you are using. Be sure to buy the pump when you buy the bicycle and have the shop attach it onto the bike.

Pros and Cons of Rim and Tire Sizes

Rims of the 700 size became popular in America for two reasons: first, because they are the same size as rims traditionally used for racing with tubular tires; and second, because of the variety of tire widths available in the 700 size. These 700 tires are stocked by every bicycle shop today and are the most common size for racing and sports bicycles.

Nonetheless, 27” wheels are still popular for touring bikes, and tubes and tires can be purchased in almost any small American or Canadian town. However, 27” tires are seldom available in continental Europe, although they are found in Britain, Ireland, and New Zealand. Hence if you will do much touring in continental Europe, you may prefer to go with 700 wheels. 700 rims originated in Europe and tires are available all over that continent. Incidentally, 700 tubes, also available all over Europe, can be stretched to fit a 27” rim.

Most 27” and 700 rims will accept a choice of three or four different tire sizes. For instance, a 700 X 25 rim is compatible with these tire sizes: 700 X 20, 700 X 23, 700 X 25, and 700 x 28.

27 x 1” tires, or 700 x 20, are the smallest and lightest, and also the most easily punctured. They are for use on smooth roads for racing, training, and fast club rides. (There is also a 27 x 7/8”.)

27 x 1 1/8”, or 700 x 25, tires are slightly larger and heavier and are for fast club rides and training on fairly smooth roads.

27 x 1¼”, or 700 x 28, larger and heavier, are suitable for extended day rides and touring on all kinds of paved roads, including those with cattle guards. They can also be used for short distances on smooth unpaved roads.

27 X 1 3/8”, or 700 x 32, the largest and heaviest, are for touring with a heavy load, or for travel on fairly smooth unpaved roads.

Meanwhile, tires for mountain bikes range from the smaller 1 1/2 road tire, good on both paved and unpaved roads, to the fat 1.95” or 2” knob-studded tire used for off-road travel on rough terrain. All mountain bike tires are compatible with the standard 26” rim. As a general rule, the larger and heavier the tire, the less the likelihood of getting a puncture.

With a little persuasion each of the 27” or 700 tire sizes can be mounted on most 27” or 700 rims, respectively. However, most rims are designed for a specific purpose and a specific tire. Hence a touring bicycle will have box-shaped touring clincher rims and they will come in 3 varieties for use with 36, 40, or 48 spokes. Wheels with 48 spokes are often used for tandems and for the rear wheels of touring bikes designed to carry a heavy load. Generally, the more spokes a wheel has, the greater the load it can carry.

Hubs and Spokes for Adult Riding

To minimize weight and air drag, racers prefer as few spokes as possible and narrow, ultralight aero racing rims are available for use with 28 or 32 spokes. In fact, modern wheel-building techniques have now made the 32-spoke wheel fairly standard for both racing and sports bicycles.

All other things being equal, for a racing or sports bicycle, I’d always go for the lightest, narrowest rim designed to match the tire I plan to use most. Modern anodized black or silver rims are among the best available.

Most better-quality bicycles today use a freehub on the rear wheel. Freehubs employ what is known as a cassette, so called because of its resemblance to a cassette tape player. Just as a cassette tape slips onto and engages splines when it is placed on the spindles of a cassette tape player, so a cog engages similar splines when it is slipped onto the cassette of a freehub. (Splines are projections on a shaft that fit into slots on a corresponding shaft, enabling both shafts to rotate together.) But unlike a cassette player, which has room for only a single tape, a freehub cassette has space for 6, 7, or 8 cogs, depending on the model. In conjunction with a triple crankset, this permits a bicycle to have as many as 24 speeds. For a more detailed discussion see “The Freewheel and Cogs.”

Using the cassette system, the freehub permits quick and easy cog changes while its superior axle support allows a stronger, longer- lasting wheel.

Irrespective of whether or not a bike is equipped with freehubs, almost all wheels today are built on low-flange hubs because low- flange hubs offer superior flexibility and shock absorption.

Hubs and rims are laced together with spokes, using an asymmetrical pattern. The most popular pattern, known as a cross-3, means that each spoke crosses 3 other spokes. A cross-3 lacing pattern provides superior strength and durability while the wheel generally remains true for a longer period (A true wheel is without wobbles and completely round.)

Butted spokes, which are thicker at the ends, are more flexible and provide a more comfortable ride than do the slightly stronger straight-gauge spokes. However, the best spokes are made of DT stainless steel, a corrosive-resistant steel manufactured in Switzer land. Use of these spokes is a good indication of quality.

For a variety of reasons, some bicycles have wheels with different-sized spokes. When you purchase a bicycle, be sure to buy half a dozen spare spokes for each spoke size used on the machine.

Turn down any bicycle not equipped with quick-releases on both front and rear axles. Quick-releases allow you to remove either wheel at the flip of a lever. Any model without them is invariably a cheaper, less desirable machine. Quick-releases are invaluable when fitting your bike into a car trunk or shipping it in a box.

As with frames, the wheel of the future may be made of compo site fiber. Such wheels, designed with just three or four fiber spokes, are already being used with success.

The Brakes

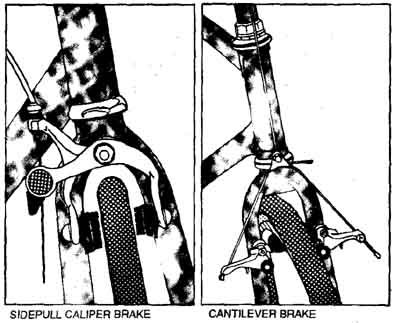

Today’s brakes feel as if they are power-assisted. Their action is powerful and positive with almost no give. There are two types:

• Side-pull caliper brakes are standard on racing and sports bicycles, and on some touring models. They are operated by aero-design brake levers in which the cable housing is concealed under the handlebar tape. This prevents use of shock-absorbing sponge grips on the handlebar top. If you prefer sponge grips, you must go back to looping the cables over the handlebar as in the days of yore. Center-pull caliper brakes are still seen on older models, and up dated designs are now being reintroduced for use on mountain bikes. Older models are quite efficient and need not be spurned while the new models are considered at least equal to cantilever brakes.

• Cantilever brakes are standard on tandems, mountain bikes, and well-designed touring models. Powerful levers, often resembling those on motorcycles, actuate these center-pull brakes, which are mounted on bosses brazed to the rear stays and fork. These are excellent brakes that can swiftly stop a bike, even on a steep down grade. If you plan to use both rear and front touring racks, check that these racks won’t interfere with brake action.

While new brake types are appearing that use more sophisticated technology, most medium-cost road bikes are likely to have side-pull caliper brakes, while most mountain bikes and many touring bikes will continue to use cantilever brakes. Whether in dry or wet weather, or on any type of terrain, there seems little doubt that cantilever brakes have greater stopping power. Yet their larger size makes them inconvenient for racing and sports bicycles. Bearing this in mind, side-pull caliper brakes are considered more than adequate for the paved-road conditions on which racing and sports bicycles operate. Meanwhile, because of the extra loads they often carry, many touring bikes are equipped with cantilever brakes.

For medium-quality bikes, whether road or mountain, top brake brands include Dia compe and Shimano Dura Ace. For riders with small hands, special “short reach” or “junior” brake levers are avail able. Brakes of surprisingly good quality are available at very reasonable cost.

Check out brakes by squeezing the levers for signs of softness or sponginess, especially on the rear. Once the brake shoes meet the rim, good quality brakes have almost no give. You can learn how brakes feel by squeezing the levers on several different models in a bicycle shop. Reject any brake that feels spongy.

Stiff cables provide superior stopping power and are a good indication of quality. Cheap cables are flimsy and they stretch. Make sure that your brakes have a quick-release needed to open up the shoes when removing the wheel. Releases may be on levers, on cables, or on the brakes themselves.

Fig. 2.3 the brakes: side-pull caliper brake; cantilever brake

Best avoided are auxiliary brake levers that parallel the top of the handlebar. Although they appear very accessible when your hands are resting on top of the handlebar, in practice these extension levers have so much “give” that much of their effectiveness is lost. Besides, they interfere with one’s hand positions and add extra weight while most riders find they can reach the regular brake levers almost as quickly. Thus extension levers are usually found only on the cheapest bikes.

The Handlebars and Stem

Correct fit of handlebars and stem makes a big difference in riding comfort, especially for women.

Most riders prefer a drop-style handlebar for a road bike because it stretches the spine, takes part of the weight off the saddle, and permits a variety of hand positions. For example, you can place your hands on the drops, on the brake lever hoods, or on top of the bar. Crouching over with hands on the drops produces greater leg power and lower wind resistance, while riding with hands on top of the bar permits a near-upright position.

Handlebars come in three different widths and should be matched to frame size. The smallest, 38 cm wide, is for shorter men and women; the 40 cm width is for medium-tall men and taller women; while the widest, at 42 cm, is for people above average height. When purchasing a bicycle, it is usually possible to exchange handlebar or stem sizes without extra cost.

Correct Stem Size Can Streamline Your Look

The stem is for fine-tuning the rider’s position. Stems come with extensions of varying lengths from 4 to 14 cm. The longest, 14 cm, is preferred by racers who like to crouch low and lean far forward. The shorter extensions allow you to ride in a near-upright position and to enjoy the scenery while touring. Shorter women should certainly opt for a short stem extension.

The stem also permits adjustment of the height and angle of the handlebars. On sports and touring bikes the top of the handlebar is usually positioned about one inch below the saddle height. Racers often prefer a lower setting. By raising the stem to its maximum height, however, you can attain a still more upright position. Not all stems are the same height. Some allow a higher position than others. If you adjust a stem to its maximum height be sure that at least two inches of the stem remains in the steering tube inside the head tube. Some stems have a minimum insertion mark above which they should not be raised. Otherwise, the stem could pull out or crack.

Various extension handlebars are now available permitting the rider to rest his or her arms on top of the handlebar while gripping a U- or triangular-shaped bar out in front. While these aerotype handlebars provide an undisputed aerodynamic advantage for experienced riders, they are primarily of interest to time-trial enthusiasts. I suggest passing them up until you gain more experience.

Mountain bikes use a flat handlebar with a sloping stem (see figure 4.7). The current trend is toward a narrower handlebar width than was formerly used. If you prefer, a similar type of flat handlebar can be fitted to most road bike models, thus allowing road bikes to be ridden in the upright position.

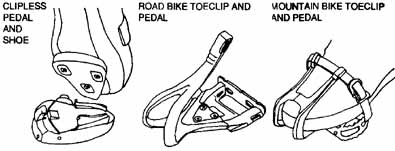

The Pedals and Toeclips

The toeclip-less pedal has revolutionized racing and is now avail able for sports and touring bikes. To enter a clipless pedal you simply engage the front of the cleat on the pedal and push down. To exit, you rotate the foot and the cleat releases like a ski binding. By locking the shoe directly to the bicycle, these step-in pedals maximize pedaling performance.

Cleats are small plastic or metal devices that are screwed to the sole of the shoe and that lock to the pedal. To function correctly, cleats for lock-in pedals must be very accurately fitted. If they are at all out of alignment, knee discomfort can occur. Moreover, clipless pedals are fairly expensive. Having cleats on the soles of your shoes can also affect your ability to walk. Some racing shoes have small, high cleats that make walking quite difficult. Cleats for sports or touring bicycles are often recessed or fitted in such a way that walking is easier.

Clipless pedals are de rigueur for racing and few racing bikes come without them. But sports and touring bikes are still available with pedals that accept toeclips and straps. Older rattrap pedals are also still made on which traditional toeclips can be fitted.

Improve Your Technique with Toeclips

For all road bikes not equipped with clipless pedals, I strongly recommend that beginners use toeclips and straps. Traditional toe- clips come in four sizes: Small fits shoe sizes 4—8; Medium fits sizes 8½ —10; Large fits sizes 10½—12; and Extra Large fits sizes 13—15. If you use a strap, place a twist in it under the pedal so that it cannot slide or move.

By a simple pull on the strap, toeclip straps can be tightened around the shoe as you begin to ride. They can be released in a jiffy by reaching down and placing the thumb on the buckle release. But since this takes some practice, I recommend not tightening the straps when riding until you gain some experience.

Tighten the straps only to the point where the shoe has a mini mum of play but which still permits the shoe to be easily withdrawn from the strap. Many experienced touring riders never use cleats nor do they ever tighten their straps beyond this point. Even when quite tight, toeclip straps still permit sufficient play to prevent any knee misalignment.

Toeclips and straps are used to maximize pedaling performance by (1) keeping the foot in the correct position on the pedal; (2) holding the shoe as firmly to the pedal as possible; (3) allowing the rider to pull up on the pedal as well as to press down.

Mountain bike pedals have a large, wide beartrap shape that provides a nonslip gripping surface. A wide double carrier toe strap is available for mountain bike pedals in either medium or large sizes. Few riders tighten toeclip straps during off-road riding, hence the straps should be set to loosely hold the shoe in place. Without toeclips, your foot may slide forward off the pedal.

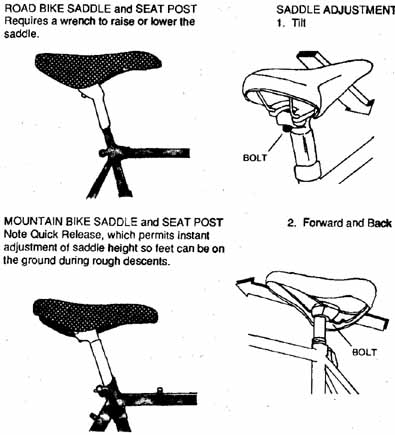

The Seat Post and Saddle

The combination of seat post and saddle can be finely adjusted to maximize rider comfort and efficiency.

The saddle is bolted to a clamp atop the seat post. In turn, this post (or pillar) fits snugly inside the upper part of the seat tube. Any desired saddle height can be obtained by sliding the post up or down in the seat tube. Once correctly positioned, the seat post is securely locked in place by tightening a bolt at the top of the seat tube.

The seat post is longer on mountain bikes — often 13” or more — and it slides easily up and down inside the seat tube. It can be swiftly locked at any desired height by flipping a lever. This allows the saddle to be immediately lowered so that both feet are in contact with the ground for descending rough terrain.

On both road and mountain bikes one or more bolts on the clamp allow the saddle to slide toward the front or the back of the bike for a distance of about two inches. Simultaneously, it allows the angle of tilt of the saddle to be adjusted. These movements allow an enormous degree of flexibility in positioning the saddle for optimal comfort and pedaling efficiency.

At one time all saddles were made of hard leather. The famous English Brooks, or the French Ideale, saddles are still available and are prized by the elite. But it requires several hundred miles of riding to break in the conventional leather saddle and to mold it to your contours. To make this easier, new softened-leather types have been developed that can be broken in more quickly. Among the best is the original Brooks Professional saddle, readily identified by its large copper rivets. These saddles literally improve with age, both in comfort and appearance. With care they will last a lifetime. However, neat’s-foot oil or another lubricant must be rubbed into leather saddles periodically while breaking them in and to keep them flexible later. These lubricants can easily stain light-colored shorts.

Nylon Saddles Can Still Be Elegant

Today most new riders opt for a nylon saddle with foam or gel padding. These saddles are less expensive and more comfortable than leather and require no breaking in. They come in all types, styles, sizes, and finishes including wider, softer saddles sculpted to fit the naturally wider female pelvis.

Many beginners believe that the large, wide-cushioned saddles used on children’s bicycles offer greater comfort. This is usually erroneous because the wider the saddle, the more it chafes. Also, the soft cushioning compresses to zero under your weight, so that you’re really sitting on the harsh metal shell underneath. In practice the most comfortable saddle is a fairly narrow man’s or woman’s touring-type saddle padded with form-fitting gel.

The gel-filled saddle is built on a shock-absorbing nylon base and is then covered with a soft, resilient pad of hydrostatic gel that flexes easily and distributes pressure evenly over a wide area. These and similar saddles are available in men’s or women’s racing, sports, touring, and mountain bike models. You can even get padded nylon saddles with a leather finish and copper rivets that resemble the finest leather saddles.

Actually the best way to prevent saddle soreness is to use a drop style handlebar, thus transferring some of the weight from your rear end to your arms. Then by riding regularly and increasing the distance, you will develop muscles in your rear end that eventually overcome seat pain forever.

Fig 2-5: Saddles, seats, and seat-posts.

Next: How to Use Gears (speeds)

Prev: Fun Adult Fitness — Not Just for Kids

top of page