.Even though mountain bikes are so prevalent as to dominate most bike shops these days, there is still plenty of choice. I’ve divided the total crop of available bicycles into a manageable number of different categories, with some sub categories. They are listed here in approximate order of prevalence. You may never have seen some of the last models listed before, but they’re all deserving of some attention.

1. Mountain bikes

a. cross-country bikes

b. downhill bikes

c. recreational bikes

2. Road bikes

a. conventional road bikes

b. time-trialing and triathlon bikes

3. Hybrids

a. regular hybrids

b. trekking bikes

c. city bikes

4. Touring bikes

5. Cruisers

6. Utility bikes

7. Roadsters and three-speeds

8. Cyclo-cross bikes

9. Fixed gear bikes

a. track racing bikes

b. fixed gear road bikes

10. BMX and trials bikes

11. Folding bikes

12. Tandems

13. Recumbents and hand cycles

In the following sections, we’ll take a close look at each of these different types of bicycle, with the objective of finding the right model for you.

Mountain Bikes

This is clearly the most common type of bicycle these days. It’s the bike to choose if you plan to ride on unpaved trails a lot. Fat knobby tires, flat handlebars, and wide-range multi-speed gearing are the major characteristics of any mountain bike. There is a wide variety of these machines, ranging from models designed for the masses to those intended for the truly devoted. They range in price from a few hundred dollars (the cheapest acceptable quality mountain bikes sell for about $300 in U.S. currency, $400 in Canada, £200 in Britain) to bikes costing literally ten times as much. They come in a range from those intended for casual use to those suitable for aggressive competition, from models without any form of suspension to those with complex suspension systems front and rear.

It has become common to distinguish between two categories of “real” mountain bike: cross-country and downhill. The simpler fat-tire bikes for less ambitious riding are referred to as recreational bikes. The latter typically have a wider seat, a higher handlebar position, and smoother tires that are more suitable for riding on pavement than on dirt. These days, even many recreational bikes are equipped with front suspension.

Cross-country bikes are not just to ride across open terrain, but are suitable for virtually any kind of use. Downhill bikes are not much fun unless you’re doing what they’re best at—riding downhill fast. Cross-country bikes may or may not have front suspension, and if they have a rear suspension at all, it will have modest travel (the distance by which it can go up or down). Downhill bikes invariably have suspension front and rear, as well as extra powerful brakes, such as disk brakes (which almost invariably cause drag while riding, making them unsuitable for anything but descending). Cross-country bikes typically have a wider range of gearing than downhill bikes, making them more suitable for steep hill-climbing.

Front suspension alone can add anything from $50 to $400 to the cost of a bike, depending on the level of sophistication of the front forks. Bikes without rear suspension are referred to as “hardtails.” Rear suspension adds another $100 to $500 to the cost of a non-suspension bike of the same quality. So, clearly, if you don’t really need the suspension, you can save yourself a significant amount by doing without.

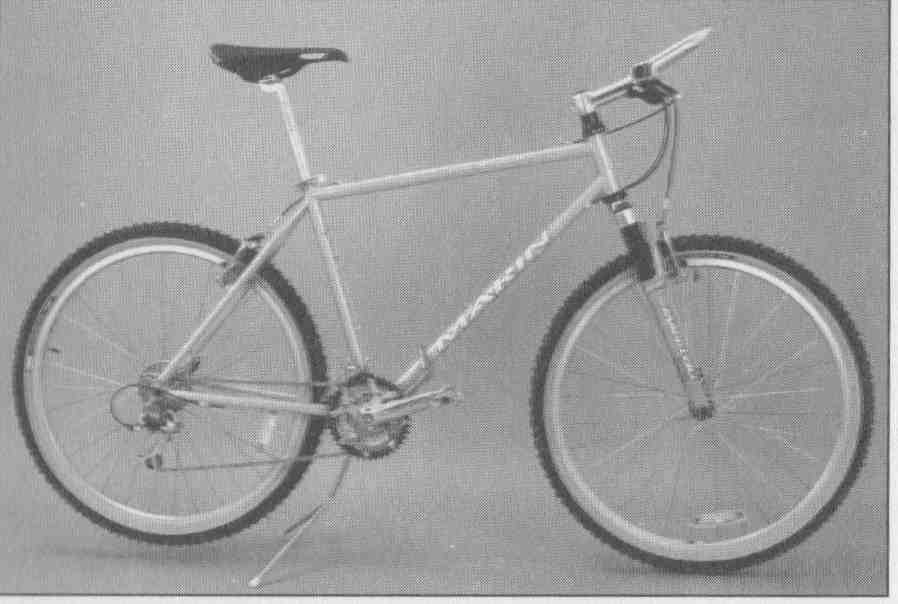

FIG. 1. Cross country mountain bike. This Pine Mountain model from Marin

has a front suspension fork only

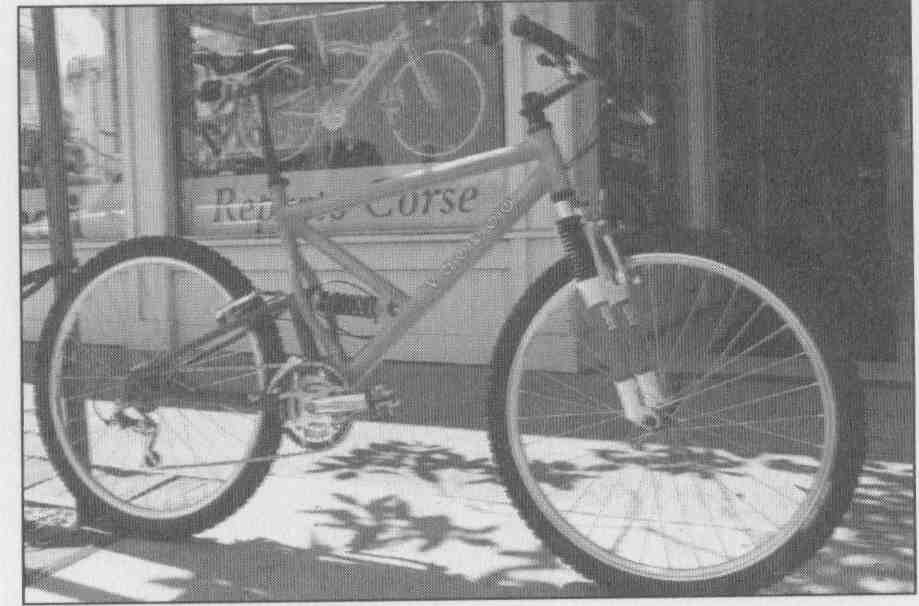

FIG. 2. Typical full-suspension mountain bike. This Ganzo model from Voodoo

is a cross-country bike suitable for moderate downhill competition.

2. Choosing a Bike Type

Front suspension has now become so common that within a short time, it may become hard to find a mountain bike without it. There are certainly uses for bikes with and without. Unless you ride on very rough surfaces a lot—be they unpaved trails or cobblestone roads— you don’t need suspension. Suspension components need a lot more maintenance than any other parts of a bike, and they also can be a real headache if they are worn or damaged. They differ a lot in their maintenance needs, with some requiring maintenance after as little as 20 hours of riding. Ask at the bike shop to see the maintenance requirements of the model you’re thinking of—and look elsewhere if it needs to be maintained too frequently.

On bikes without suspension, the tire pressure does the same job. By inflating the tires more or less, you can control not only how comfortable the bike is on the terrain you’re dealing with, but also the amount of traction when accelerating, climbing, cornering, or braking. The thicker the tire, the more flexibility you have in those adjustments. For general use on unpaved trails, a tire diameter of 2.125 inches is considered optimal for general use on unpaved trails, while narrower tires may be fine if you ride mainly on paved roads and paths. Keep in mind that your choice should not necessarily be determined by the average but by the extremes—choose a bike that’s equipped for the worst terrain you’ll be riding.

Mountain bike brakes are controlled from easily accessible levers, and those brakes are powerful. In fact, they’re often so powerful that they can be dangerous to the novice used to the ineffective brakes on the bikes he remembers from the past.

Apply the front brake suddenly with full force, and chances are the rear wheel lifts off. (The thing to do in response is to back off on the lever for the front brake.) In Section 9, “Getting Familiar with Your Bike,” I’ll show you how to achieve the control needed to ride safely.

Road Bikes

A road bike is what used to be referred to as a “ten-speed” until the mountain bike became the dominant variety of bicycle in America. It’s the bike to use if you ride mainly for fitness, sport or recreation on roads rather than on unpaved trails. The two main categories of road bike are conventional road bikes and special time-trialing and triathlon machines.

Special triathlon and time-trialing machines are built only for speed and not for maneuverability The conventional road bike is the safer one to choose if you will be riding in traffic and among other cyclists a lot. You don’t lean forward as much as on the triathlon bike, resulting in a slight aerodynamic disadvantage, but you’ll have a lot better control over the bike and a better view of the road ahead. Except for the most expensive special triathlon and time-trialing bikes, most bikes sold for that purpose are regular road bikes to which triathlon bars have been added, and these are more versatile than the specialty bikes that some of the champions choose for triathlon and time trials.

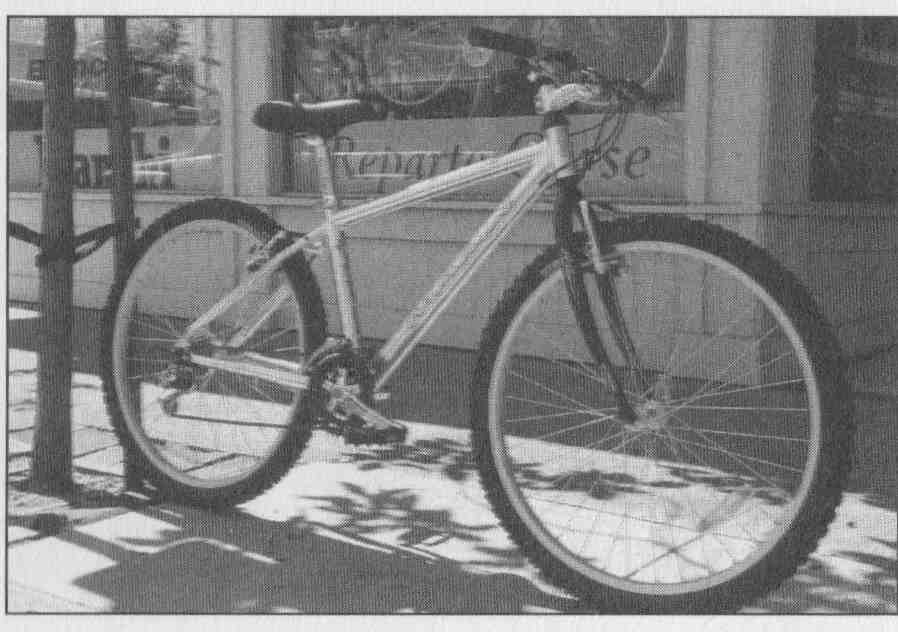

FIG. 3 Typical recreational bike. Like most other bikes in its class, this

Bobcat Trail model from Mann has no suspension. Bikes like this are designed

for an upright riding position.

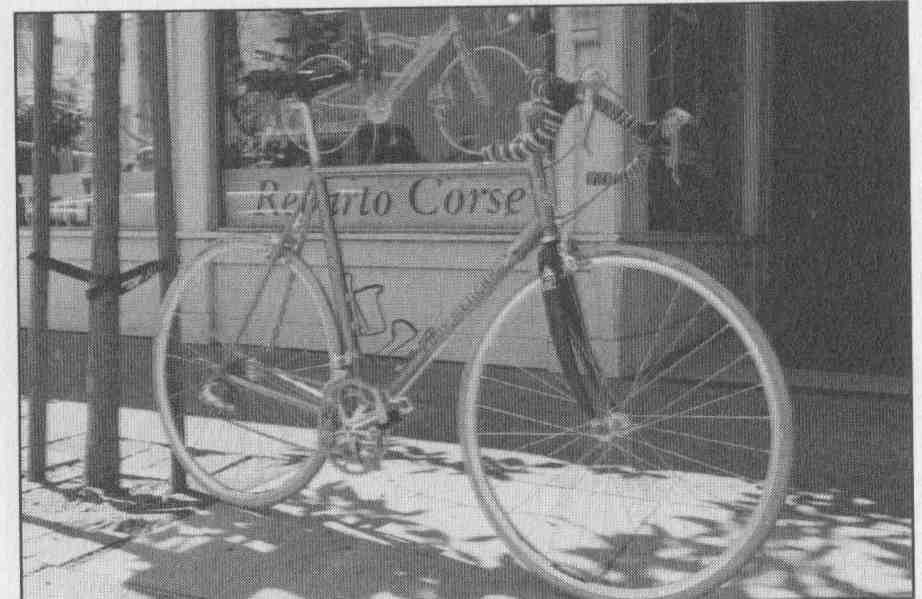

FIG. 4 Modern road bike. This Titanium 4X model from Eddy Merckx has an American-made

titanium frame built by Litespeed and is equipped with Shimano Ultegra components.

The road bike has skinny tires, usually of the size 700 C, and I shall save you the explanation why they’re not 700 mm (28 inches) in diameter, but only about 675 mm (27 inches). Their thickness can be anything from 18 mm (less than inch) to 32 mm (1 inches). All those tires will fit on the same rim size. (Real racing bikes may use special so-called sew-up or tubular tires, which are mounted on special rims.) Although the narrowest tires generally are the lightest, and offer the least rolling resistance, you should select thicker tires if you plan to ride on surfaces that are less than perfectly smooth. The narrowest tires must also be kept inflated very hard to minimize the risk of damaging them—making them even harder on rough roads. If high speeds are your thing—whether for triathlon, time-trialing, road racing or just for the hell of it—you’ll want the skinniest and lightest tires, inflated to a high pressure.

For smaller riders, there are other tire sizes, but the frame has to be built around the particular tire size, and that puts them into the category of custom-built bikes. The available alternate sizes are 650 C (about 26 inches diameter) and 600 C (about 24 inches diameter). In addition to custom frames, there are only a few manufacturers who offer quality road bikes in those sizes suitable for small women and youngsters.

The other main characteristic of a road bike is the use of drop handlebars. They may seem uncomfortable at first, but they actually are more comfortable than flat bars in the long run. This is the reason why long-distance tourists and others who ride continuously for two hours or more tend to prefer them over straight handlebars. Their comfort is mainly due to the fact that you can hold them in many different ways—on top near the middle, in the bends above the brake levers, on top of the brake levers, or low at the ends. You can change the hand position, and as they say, “a change is as good as a rest.” Triathlon bikes will have either special handlebars or regular drop bars with a forward extension that allows you to lean forward very far and keep your body very low. This increases the risk of a pitchover accident, so don’t apply the front brake suddenly in this position.

The brakes on a road bike are harder to reach and operate than they are on a mountain bike, but once you’ve got the knack of it, you’ll find them quite adequate.

The gears—usually 16 or 18, rather than the ten that came on the original ten-speed—can be operated either from shifters integrated with the brake levers on the handlebars, or from separate shifters mounted on the side of the frame’s down tube. The pedals on most road bikes are of the clipless variety, meaning they must be used with dedicated cycling shoes that have matching clip-on cleats in the soles.

Hybrids

About five years into the mountain bike craze, some manufacturers took note of the fact that most of their customers didn’t really ride their mountain bikes off-road a lot. That’s how they came up with the idea of creating the hybrid. It’s a bike that combines some of the mountain bike’s characteristics in a package that is easier to ride on the road. If that’s the use you’ll give your bike, today’s hybrid bikes bear looking into.

Most manufacturers of mountain bikes also offer hybrids in the same price range as their cheaper mountain bike models—usually about $300 to $600 depending on the quality of the components installed. They’ll look similar to a mountain bike but with somewhat narrower and less knobby tires, and a more upright rider position. Most hybrids are equipped to allow mounting racks, fenders, and other gadgets that make a bike more practical for utilitarian use. Hybrid bikes usually have 700 C tires, but with a much thicker diameter and a lot more rubber than those used for road bikes.

The concept was refined in Europe, and some of those bikes evolved into what are called trekking and city bikes. Trekking bikes are hybrids designed for touring use. They have sturdy luggage racks, and often fenders, lights, and an integrated lock. City bikes are similar and are intended for urban commuting, shopping and everyday transportation.

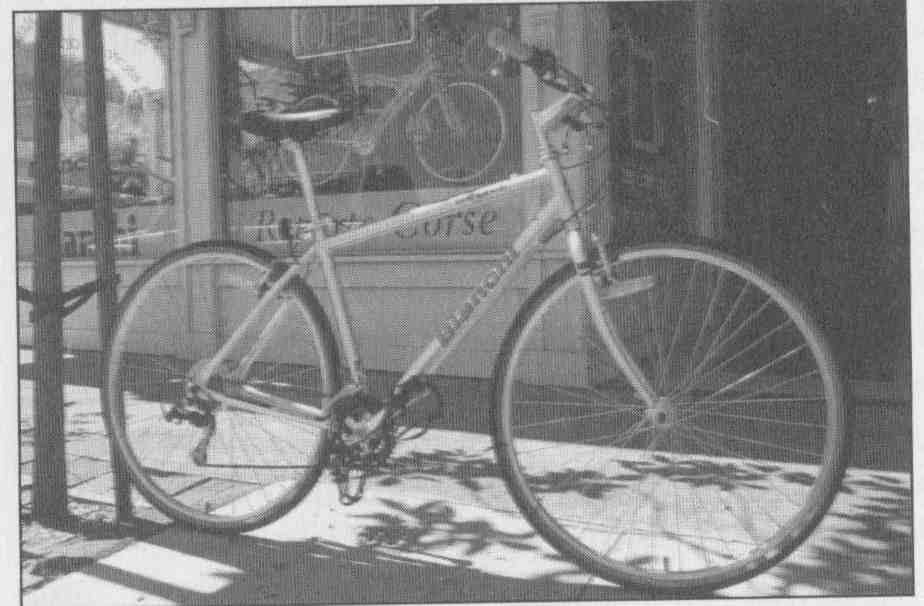

FIG. 5. Typical hybrid bike. Like other hybrids, this Boardwalk model from

Bianchi is most suitable for recreational and transportational riding on roads

or paved paths and smooth trails.

Like the mountain bike, the hybrid has wide-range gearing, flat handlebars, and powerful brakes. The same warning mentioned for mountain bikes applies here too: get used to the way those brakes operate so you develop a feel for their behavior.

Other Bikes

Although mountain bikes, road bikes, and hybrids together account for the lion’s share of all bicycles sold these days, there are quite a few other models. These will be described briefly in the sections that follow.

Touring Bikes

A touring bike is similar in appearance to the road bike, but with the wide range gearing, powerful brakes, and sturdy tires of the hybrid. In addition, it’s equipped with braze-ons for racks. Few manufacturers have been offering them recently, but they seem to be making a bit of a comeback. A good touring bike is of course also suitable for other kinds of riding. They are designed and built to be stable and comfortable on long distances, and to carry luggage safely. They vary in price from about $600 for an adequate mass-produced touring bike, to $2,500 for a high-end version.

If you really want to go touring a long way from home, the bike should not be too sophisticated. When you’re a hundred miles from the nearest bike shop, or that shop is in a primitive country where bikes are not fancy toys but simple amenities, you won’t be able to get replacement parts for anything but the simplest components. So in that case, forget about clipless pedals, integrated brake-and-gear levers, high-power battery lighting, even cartridge bearings. Get the simplest, most straightforward equipment available. Just make sure it’s durable, and above all, serviceable.

Cruisers

Cruisers are back, or so it seems. These bikes with fat tires, a broad saddle, and wide handlebars are intended for laid-back, unambitious riding over short distances. They’re not very comfortable, and they are not very suitable for climbing hills, riding fast, or riding far. They appeal to the nostalgic sentiments of America’s kids in their late forties and fifties. It’s an OK bike to get if you just want to ride short distances and like the feeling that comes with this kind of bike.

Although department store cruisers today are no better than the originals, many bike shops sell cruisers that are a lot more sophisticated than the original. These modern high-quality cruisers use aluminum for many components; well-built, relatively light frames; and either derailleur gears, or multi-speed hub gears. The brakes can be anything from the traditional coaster brake, operated by pedaling back, to modern rim brakes borrowed from the mountain bike.

Utility Bikes

In the mid-1990s, Shimano, the major manufacturer of bicycle components, decreed (probably correctly) that the world was waiting for a different kind of bike, a bike that would be suitable for everyday transportation, requires little maintenance and finicky operator awareness. They boosted the concept of this kind of bike, the new utility bike, by introducing component groups specifically designed for that kind of use, first centered around internal hub gearing and hub brakes, now mainly with derailleur gears. In addition, they sponsored competitions for the most innovative use of those products in new bike designs.

So far, not many of the real utilitarian results have hit the American market (unlike in Europe, where they are embraced by many major manufacturers and the cycling public). Specialized and Bianchi introduced elegant Italian-built bikes based on this concept, and Wheeler brings in some models from Japan. My guess is that it will perhaps take a few years, but eventually there’ll be plenty of choice.

A good utility bike should be suitable for riding and carrying things under all conditions, including rain and snow. That means not only racks and fenders, but also an enclosed chain-guard (to allow you to ride it with regular street wear), generator lights (so you can count on having lights available even if you weren’t planning on riding in the dark), internal hub gears, and internal hub brakes (both of which work in any kind of weather). Count on spending $600 or more for a good multi- speed utility bike.

Roadsters and Three-Speeds

Although still available in Britain, they don’t bring them into the U.S. anymore. Roadsters first entered the U.S. market under the guise of “English Racers” in the early fifties, because they seemed like racers when compared to the 45-pound bikes most Americans were riding at the time. But in the U.S., these bikes have virtually disappeared from the bike trade by now.

If you like the simplicity and upright posture they offer, as well as some of the same virtues that are on my wish list for the ultimate utility bike, look at garage sales and bike swaps—lots of those machines with Sturmey-Archer three-speed hubs, elegant fenders, and upright handlebars are being sold for peanuts.

A little attention will turn most of them into very serviceable machines. (See Section 6 to learn more about buying a used bike.)

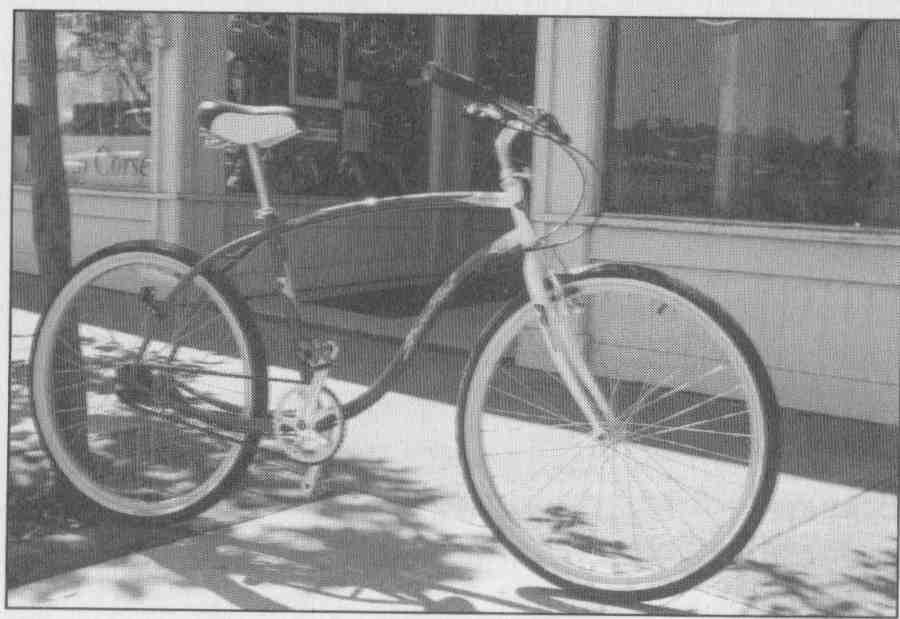

FIG. 6.Typical modern cruiser This Street Rod model from Electra Cycles is

styled after the Schwinn cantilever frame-bikes but comes with Shimano four-

speed internal hub gearing.

BMX and Trials Bikes

Running on 20-inch diameter fat-tire wheels, BMX bikes were the first modern bikes intended for off-road cycling, making them precursors to the current mountain bike craze. They are used to best effect on special courses and are less suitable for longer bike rides. Some of the technology for competition-level BMX bikes is quite sophisticated and has rubbed off on the mountain bike.

The 24-inch wheel equivalent of the BMX bike is referred to as either cruisers (not to be confused with the more common 26- inch cruisers) or dirt bikes. They also have knobby tires.

Trials bikes are also derived from the same stock, and are typically 24-inch-wheel machines with small frames that are particularly suited to doing tricks.

Cyclo-Cross Bikes

Cyclo-cross is the original off-road form of bicycle racing, which preceded mountain biking by some 60 years. A cyclo-cross bike looks like a road bike. It has relatively narrow knobby tires and drop handlebars. But the gearing is similar to the wide range gearing of the mountain bike, and the same cantilever brakes are used that were installed on early mountain bikes. The cyclo-cross bike is a lovely lightweight alternative to the mountain bike for off-road riding, but it’s much more fragile and not as easy to ride. Expect to pay at least $1,000 for this kind of bike.

Fixed-Wheel Bikes

The fixed-wheel bike looks like a road bike, but instead of derailleur gearing it has a directly driven rear wheel. No freewheel, no gears. Traditionally used for bicycle track racing, this ultimately simple machine has recently been rediscovered for urban use, primarily by bike messengers. Because you can’t stop pedaling when going around a corner, it’s important that the frame be designed specifically for this kind of drive. Fun to ride, beautifully simple and straightforward, good practice for developing a smooth riding style, but torture on steep hills. Expect to pay at least $600 for anything worthy of the name.

The difference between a regular track racing bike and a “street fixed-wheel bike” is that the former does not have a brake, while the one you might want to use on the road should at least have a front brake. In the rear, just trying to restrain the pedals will give all the braking effect you can expect there.

Folding Bikes

The idea of reducing a bicycle to a package compact enough for transportation is almost as old as the bicycle itself. In recent years, responding in part to the restrictive policies for carrying bikes on planes and other forms of public transport, many innovations have come to market. It’s worth considering if you travel a lot and find a use for a bicycle wherever you go. Good folding bikes start at about $600, but you can pay as much as $5,000 for a top-of-the-line Alex Moulton.

Folding bikes fall into several different categories, although most are considered utility bikes. There are folders with skinny tires that behave like road bikes, and there are those with fat tires that feel like mountain bikes—some of them with front and rear suspension. There are even folding tandems—an engineering challenge if ever there was one, due to the high forces working on a tandem frame.

Perhaps the most common, though rather marginal, folding bike in the U.S. is the DaHon—it folds very ingeniously, but it suffers from the restraints placed upon the design by the manufacturer’s pricing policy: cheap sort of precludes good.

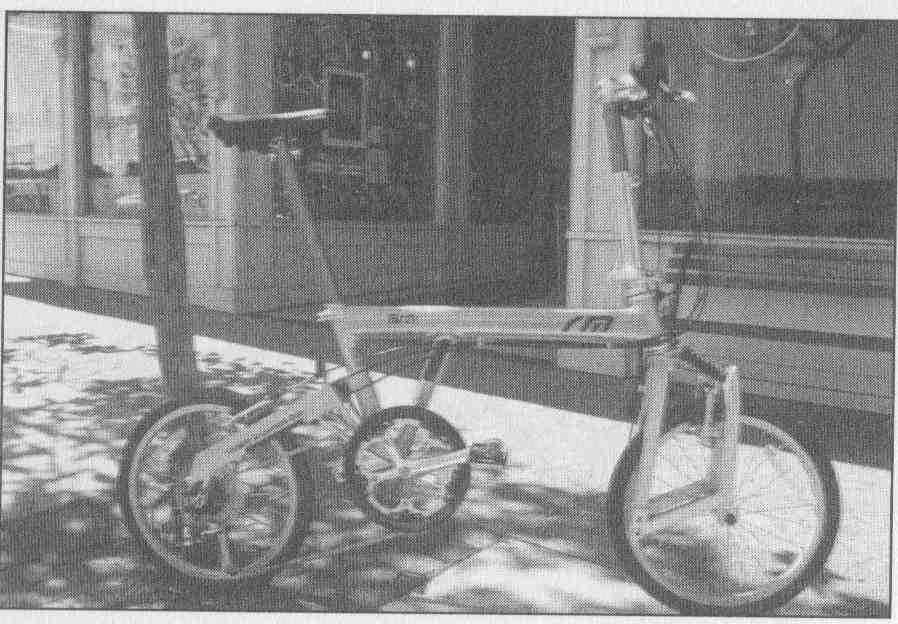

FIG. 7. Modern lightweight folding bike. This Birdie by Burley rides like

a full size bike, thanks to its Sophisticated full suspension system.

Green Gear Cycling of Eugene, Oregon, makes a series of high-quality folding machines under the name BikeFriday, while its neighbor Burley, best known for its tandems, markets a German design called Birdie. Other folding and collapsible machines include the famous Alex Moulton small-wheeled suspension bikes, and the very ingenious and simple Brompton, also from England. The Montague bikes are a case apart; they are full-size bikes, with regular size wheels, that fold compactly. A few other rather sophisticated full-size bikes are much like it in that they can be taken apart with the use of special connecting fittings in the main tubes, allowing the bike to fit in a compact carrying case.

Tandems

There has been a resurgence of tandems—bicycles built for two—during the last ten years or so. Road and mountain bike versions are available. There are even track-racing tandems and recumbent tandems. The tandem’s advantages are that it keeps riders of different skill levels together and that it travels faster than a single bike, especially against the wind. On the down side, all tandems are heavy, cumbersome, and expensive. The equivalent tandem to a $600 road or mountain bike will weigh 40 pounds and cost $1,500, and it seems the sky is the limit for the price of upscale models.

FIG. 8. Modern road tandem. This is the author’s custom-built tandem, based

on a frame of his own design, built by California frame builder Bernie Mikkelsen.

Braking is a big problem on most tandems, certainly when going downhill fast. It’s advisable to practice a lot to learn about the limitations of braking effectiveness at speed before taking the tandem out on a serious ride. Other aspects of tandem riding also should be practiced, because this long and somewhat cumbersome machine acts differently from the bike you’re used to, not to mention the need for the two partners to learn to work together and coordinate their efforts.

When buying a tandem, take your prospective partner along. That way, you can select a bike that both of you like, and both of you benefit from the instructions given at the bike shop.

Recumbents and Hand Cycles

This is an entirely different category of cycles (both bicycles and tricycles can fall into this category). Recumbents differ from the conventional bicycle in that the rider sits leaning back with his or her legs pointing forward rather than dangling down. There are many different models, but very few of them are available at regular bike stores. Their prices start at about $1,000 for a bike that performs well, and are virtually open-ended at the top.

On some recumbents, you can install fairings that keep the rider dry in bad weather and improve aerodynamic performance. Although they can be rather cumbersome due to their often great length, they can be a great solution for people who find conventional bikes uncomfortable. They also may have a safety edge because the rider’s low mass center and the long wheelbase prevent most mechanisms that lead to dangerous falls.

Hand cycles are usually set up like recumbents, but are propelled by hand-cranking instead of being pedal-driven. They allow people with lower body disabilities to keep up with others on the road. Although you won’t find many shops that stock hand cycles (or recumbents for that matter), they should have the information available to special-order one for you.