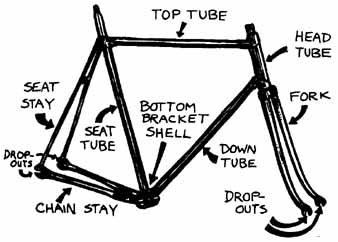

DESCRIPTION AND DIAGNOSIS: (C, R, M) The frame is more than it might seem. It is not just a lopsided diamond and two triangles of tubing stuck together somehow. It is the heart and soul of a bicycle. It is not just the most expensive part of the bike: it is the single most significant part in determining the quality of a bike. The fork is equally important. A great, lightweight fork can make all the difference in how a bike climbs, descends, and responds to the terrain. And the way that the frame and fork work together is critical, too.

Frame

(C, R, M) The frame and fork are also the most difficult parts of your bike to repair. If you completely crumple any of the tubes of your frame, or if you smash the forks, or wear out the shocks when you are out in the middle of no where, you can’t do much about it. If the bike is still rideable, ride it very gently; if not, walk. There are some tricks you can use—if a fork blade breaks, whittle a stick down to the right diameter, then jam it into one end of the blade and push the other end of the blade over the other end of the stick. But such frame and fork repairs are rarely workable. Trailside repairs on suspension-frame bicycles are even less likely to save you from a long walk home.

(C, R, M) Prevention is the best medicine for frame and fork problems; try to buy a really light, durable frame and fork to start with. Frame technology and suspension technology for shock forks and fully suspended bikes are changing constantly, but one rule of thumb you can always use is this:

(C, R, M) a new-tech bike weighs more or is more prone to failure than a tried-and-proven, steel-tube bike, it’s probably not worth spending extra money, time, and energy on. Whatever bike frame and fork you buy, respect their limitations by using good techniques going over and around obstacles. Good frames and forks don’t usually break unless you are riding foolishly. No matter what anybody claims about certain shock forks or suspension frames, it is foolish to ride full-speed down a rocky mountainside unless you have spent a LOOONG time learning the art of high-speed descent.

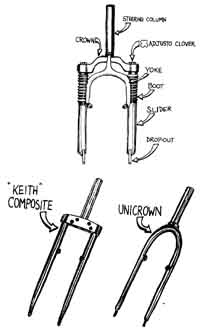

forks: Standard, "Keith" composite and Unicrown

(C, R, M) One note about paint: new frames usually have good paint jobs. Keep the original paint on a frame as long as possible. Keep the bike out of the rain and touch up scratches with auto touch-up paint to prevent rust. To re paint a frame you have to take everything off it. If you’re up to that, US the various sections of this guide that apply. If not, have a good shop do the work. Do-it-yourself painting means first thoroughly stripping the old paint (use a liquid paint remover and AVOID BREATHING THE FUMES). The frame has to be perfectly clean and dry. Then spray on a coat or two of primer, making each coat as smooth as possible and always letting it dry thoroughly before spraying the next coat. Then spray on several layers of epoxy paint. Or you can take the bare, prepared frame to an auto paint shop and get a bake-on job. You might get it done pretty cheaply if you’re willing to have them put the frame through the works with an auto body. Just wait for one that has a color you like.

PROBLEMS: (M) Front end bent in: So you hit a boulder. Or was it a log? Or was it that dip at the bottom of the gully that you thought you could pull the front end up out of, but you didn’t quite make it? Oh, yes, it can happen to any of us, and has happened to many of us. The result is that either your fork or your down and top tubes are bent, or all three are bent, and now your front wheel hits the down tube so you can’t ride home.

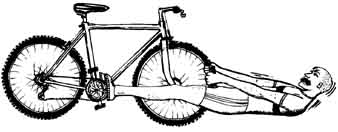

(M) Try this last-ditch method of straightening the front end of your bike a bit; it won’t make the bike perfect by any means, but it may get you home. My thanks to hollow_man for this trick; he showed me how to do it when we were way out in the woods, and a guy from Topanga, CA “lunched out” in a rocky creek bed.

(M) Have a friend hold the bike upright, or prop it against a post or a tree, and sit down on the ground with the front wheel between your thighs. I know that’s a weird position, especially if your friend has a sadistic sense of humor, but you need to fix the thing, right? Push the pedals around with your toes until the right crank (the one with the chainrings) is pointing down and the left crank is pointing up. Place your left foot on the chainring, with your heel against the right crank, and place your right foot against the bottom bracket shell, with your toes up along the left crank, as shown in Illustration 5-3.

(M) Now grab either the ends of the fork or the rim of the wheel where it is nearest to your chest. The taller you are, the easier it’ll be to pull on the rim. If you are less than five feet tall, you may have to take the front wheel off so you can pull on the drop-outs at the ends of the fork.

Pulling Out the Front End

(M) When you have a good grip on the rim or fork, first straighten your back (you’ll strain it if it’s curved), then try to hold the fork or wheel absolutely still with your hands as you push the bottom bracket and the rest of the bike away from you with your feet. Make your legs do the work, not your back and arms. If you have a light, unreinforced frame and fork, you may be amazed at how easily you can pull the front end of the bike out. Some super-heavy-duty frames and forks may be impossible to straighten using this method.

If your fork is the only thing that is bent, and you have a really sturdy front end on your frame, you can try another straightening method; it is primitive, but if you are stuck out in the middle of nowhere, you may want to try it anyway. All you have to do is turn the front wheel all the way around backwards (you may have to undo the front brake and loosen the stem to do this), then put the front wheel against a tree and shove the bike from behind. Easy does it. I saw a desperate racer try this method once, only he sort of hurled the hike down against the ground on its reversed front wheel, and, Instead of neatly straightening his front fork, he neatly crumpled both his top and down tubes, which neatly took him out of the race since the nearest spare bike was about five miles away.

There are other ways to pull a front end out, like wedging the forks in the crotch of a tree and levering the frame back, but I think these methods have much more potential for ruining the bike than fixing it.

(M) Whatever you do to straighten things out, don’t keep using your bent and straightened fork or frame. When you have limped home, take the fork or the whole frame to a first-rate bike shop and see if the thing can be accurately straightened by a professional frame-maker, or if it should be re placed. And next time, use a bit more finesse to get over those rocks, logs, and holes at the bottoms of gullies.

(M) Shock forks squeaky. This can be due to worn parts, or it can be due to simple lack of lubricant, especially on elastomer-based suspension forks. For these forks, first ad just the forks to a loose setting if you can, then pull the boot off the upper part of the shock fork, dribble a light bicycle lubricant such as Tri-flow around the top of the lower tube, and work the fork vigorously a few times to get the lubricant down in there. If the squeakiness is related to looseness and fork flutter, take the fork to a good shop for overhaul.

(M,R) Fork flutter. When you put on the front brakes as you are flying down a bumpy single-track, the front end of your bike starts to waggle and jerk fore-and-aft under you. If you glance down (don’t stare; you are flying down a hill, remember), you can see the fork flexing or fluttering fore-and-aft.

(M) The flutter takes on a rhythm all its own, which can throw off your judgment of obstacles ahead, and even throw you into an “endo” (over the bars), if the hill is steep and you have to put the brake on hard. The problem is a bad wave of vibration repeating itself in the fork. The harmonics from hell.

(M) If you have a shock fork, the flutter is probably a result of looseness due to wear and tear on the inner workings of the shock absorbing mechanism. Shocks are not made so you can take them apart and fix them yourself. Take your wobbly shock fork to a first-rate shop that repairs the brand and model you have, and be prepared to pay a tidy bundle for an overhaul.

(M) Fork flutter on rigid forks is caused by brake shoe judder and/or bouncing over bumps, amplified by anodized or crud-crusted rims. Certain combinations of fork type and frame geometry can make flutter more of a problem. In my experience, round, thin-gauge, wide-diameter, straight steel fork blades, with a short offset and a fairly steep head angle, are more susceptible to flutter than other types of forks. But I have heard of small-diameter, curved-blade forks fluttering, too. The cheap solution to the problem is to toe in your brake shoes. (See brake shoes squeaking or fuddering in the “Brakes” section.) If that and cleaning or sanding your rims don’t help, you have to ride home carefully, taking it easy on the bumpy down hills, then buy a different fork.

Next:

Prev: Headset

top of page Products Home